Energy demand reduction measures come with a host of co-benefits and should be used to bring forward energy demand policies

Reducing energy use (known as energy demand reduction, or EDR) is a key lever in planned pathways to help meet 2050 net-zero emissions targets. The immediate benefits of EDR to climate change mitigation are to reduce fossil fuel based greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and also to reduce the pressure on other climate levers (e.g. renewables and carbon sequestration). In fact there are many other secondary, or ‘co-benefits’ of EDR.

Some are well known and are more intuitive for us, such as health benefits (from reduced air pollution) or reduced household energy bills (from lower energy use in a better insulated house). However, co-benefits are more numerous and much more widespread, they are located in different, often siloed places, such as health, economics or energy efficiency literature. This spread of literature makes it hard for policy-makers to identify and include them in their appraisal of EDR policies. The default instead is to revert to a simple cost-benefit analysis, where the cost of the implemented policy measure (think home insulation) is set against only the energy saving benefit (reduced energy costs). Co-benefits are actually much broader, and much more inter-related.

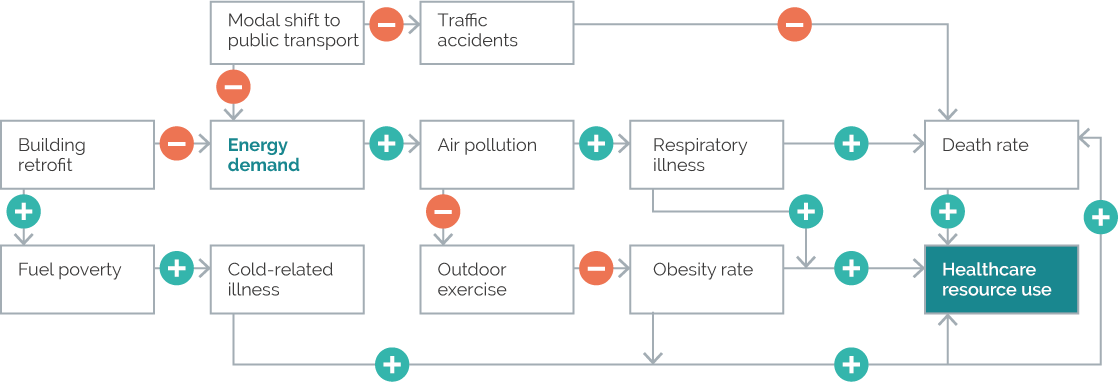

Image description

- A modal shift to public transport reduces the number of traffic accidents and lowers energy demand. Fewer traffic accidents reduces the death rate which has a positive effect on healthcare resource use.

- Building retrofit reduces energy demand and has a positive effect on fuel poverty, which in turn lowers the rate of cold-related illnesses with a subsequent positive impact on healthcare resource use and a lower death rate.

- Reducing energy demand lowers air pollution which has a positive impact on respiratory illness, reducing the death rate and having a positive impact on healthcare resource use.

- Lower air pollution is better for outdoor exercise, which in turn helps to reduce obesity rates with a positive impact on healthcare resource use and a lower death rate.

If a much broader set of co-benefits can be collated and included in EDR policy-design, this could be a game-changer, as the sum of all benefits will be much larger, making EDR policies much more of a no-brainer for decision makers.

To help contribute to that need, research conducted at the University of Leeds Sustainability Research Institute reviewed the co-benefits associated with EDR literature. The research has been published as an open access paper in Energy Research & Social Science.

From our review of 53 selected papers/reports, we found several important results. First, co-benefits are much broader than just ‘health’: in fact, we identified 86 unique co-benefits across five different categories (Health, Energy Security, Economy, Social, and Environment) with Economy having the highest number of mentions. Second, our top five mentioned individual co-benefits were: health/environmental impacts of reduced air pollution (52No.), greater energy sovereignty (26No.) higher employment (22No.), reduced fuel poverty (22No), and greater economic productivity (21No.). Third, whilst 31 of the 53 papers/reports prioritised the use of the term ‘co-benefit’, there was actually quite a diversity of terms: with multiple benefits (10No.), Non-energy benefit (5No.), ‘ancillary benefit’ (4No.), ‘multiple impact’ (2No.), and ‘coeffect’ (1No.) terms also used.

Last, importantly, only 21% the surveyed papers/reports attempted actual quantification of energy reduction co-benefits, and most of those were concerned only with air quality. This is a key weakness in current co-benefit research. We developed a matrix to present some of the opportunities and challenges faced in quantifying key co-benefits across varying time scales.

| Quantifiability | Short term | Long term |

|---|---|---|

| High |

|

|

| Medium |

|

|

| Low |

|

|

To help move the field forward, we propose a four-step plan for improving the use of co-benefits, deepening the evidence base to improve climate change mitigation policy:

- Work on standardisation of co-benefit terms to aid understanding and quantification

- Greater focus on cross-disciplinary co-benefit research to avoid research siloes

- Greater research on primary quantification of EDR co-benefits to establish functional methodologies and raise awareness of policymakers

- Given high barriers to entry on co-benefits, greater efforts are needed to take co-benefits to policy-makers.

In summary, the lack of wider inclusion of quantified co-benefits, beyond health, is a key current issue. Doing so could have a groundbreaking effect, shifting the narrow cost-benefit narrative to a much broader assessment of the cross-disciplinary co-benefits, overcoming a key barrier to EDR policy. The scope and depth of EDR policies to meet our net-zero goals could depend on it.

Banner photo credit: Kolar.io on Unsplash