Our guidance provides some ideas and suggestions for writing the impact sections that may be required as part of a research proposal. This includes how to find stakeholders and engage with them.

Our guidance provides some ideas and suggestions for planning impact that may be needed as part of a research proposal. This includes how to find stakeholders and engage with them.

A clearly thought through and acceptable statements about how your work will engage with stakeholders and maximise impact and societal benefits is an essential component of a research proposal and a condition of funding. However, there is no single activity or approach that will ensure that your project achieves impact.

This guidance was originally developed when a Pathways to Impact statement was required in many research proposals, but this has now changed with impact more integrated into the various sections of the call. In many cases the impact requirements are in the ‘How to apply’ section.

Specifically, within the ‘Vision’ section:

- Explain how your proposed work impacts world-leading research, society, the economy or the environment and

- We expect you to identify the potential direct or indirect benefits and who the beneficiaries might be.

Within the ‘Approach’ section:

- Explain how you have designed your work so that it will maximise translation of outputs into outcomes and impacts

And within the ‘Applicant and team capability to deliver’ section:

- Evidence of how the team demonstrate experience and/or skills that ensures that the work contributes to broader users and audiences and towards wider societal benefit.

In order to address these requirements each proposal needs its own tailor-made set of activities so it cannot just be a cut and paste process. Here we give you a few pointers, some questions to work through and a suggested approach so that by the end you will have ideas about what impact your research could have, and what activities you could carry out to achieve the impact you are looking for.

1. What is impact?

Impact is the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to scientific advances, society and the economy. This occurs in many ways – through creating and sharing new knowledge and innovation; inventing ground breaking new products, companies and jobs; developing new and improving existing public services and policy; enhancing quality of life and health; and many more.

Types of research impact

UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) aims to achieve research impact across all its activities. This can involve academic impact, economic and societal impact, or both:

- Academic impact is the measured contribution that excellent research makes to scientific advances, across and within disciplines, including significant advances in understanding, method, theory and application. This goes beyond an academic paper in your selected journal as it is across disciplines and other disciplines may not read your selected journal.

- Economic and societal impact is the measured contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy, of benefit to individuals, organisations and nations.

The impact of research can include:

- instrumental impact – influencing the development of policy, practice or services, shaping legislation and changing behaviour

- conceptual impact – contributing to the understanding of policy issues and reframing debates

- capacity building through technical and personal skill development.

Why does impact matter?

- Many research grants (UKRI, Horizon Europe, Innovate UK) are spending public money which means that we need to demonstrate the benefits of that investment to society = accountability

- Research can be improved by engaging with a broad range of potential beneficiaries = quality

- Shortening the time to benefits by pro-actively engaging beyond your own discipline, and increasing the impact we know our investments have = maximising benefits

- It enhances UK attractiveness for research and innovation investment = reputation.

You do not need to predict exactly the impact of your research, it is more about providing suggestions about what impact you might realistically have. Impact is about who the beneficiaries of the research might be and how you are going to work with them to shorten the time between discovery and use of the knowledge.

We would encourage you to think about impact at the beginning of the proposal preparation stage.

The critical questions to ask yourself about your project are:

- Who might use the outputs of your research?

- How can you make the impact happen?

2. Links between impact and knowledge exchange

A high quality approach to enabling impact should include clear awareness of the principles and practices of knowledge exchange i.e. a two-way sharing of knowledge, as opposed to dissemination of knowledge only. This includes the application of these principles and practices in co-productive research.

This may include:

- consulting users when planning and strategising for impact

- designing training workshops and events for specific user groups

- planning space to take advantage of unexpected opportunities

- committing to principal and senior investigator time on knowledge exchange and impact activities.

ESRC states that ‘The strongest proposals we receive show a mindset in which research, knowledge exchange and impact are linked together.”

Guidance on these links are available fromCREDS describe the way research, promotion, engagement, knowledge exchange and impact fit together as an interative journey with a series of four guides on:

- The research to impact journey: an overview

- How to promote research

- How to undertake knowledge exchange

- How to monitor and record impact

ESRC also has a guide on How to do effective knowledge exchange.

3. Who will benefit from your work?

Make a list of all those types of organisations who might use the outputs – this is also called ‘stakeholder mapping’. We suggest taking up to a day in total to tackle the following steps – draw up an initial list, discuss it with colleagues, do some further market research to prioritise and finally decide on the chosen short-list. The more specific you can be, the easier it is to develop targeted outputs for your chosen audience. The key is market segmentation – groups of people that have needs in common: sub-dividing your list into smaller groups will help.

You might like to separate them into:

- Those that would be interested in the methodology, for example, researchers in other disciplines,

- Those that would be interested in the results directly, for example, trade bodies or policy non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or consultants that collate information and use it for evidence reviews

- Those that might be interested in the results if they were tailor-made for them (selected sections only and potentially taken onto the next stage by providing recommendations/benefits/implications that link to their motivation)

For example:

- Government – national, devolved, regional or local

- Businesses – specific industry sub-sectors, innovative businesses, (e.g. high-use sectors), commercial, retail

- Intermediaries – those who will pass on information to others e.g. media, trade press, trade associations, professional bodies.

Think about:

- Why would this group of people be interested in this research?

- What motivates them?

Their motivation could be:

- The need for knowledge

- More detailed information

- Making the case for new investment

- Maintaining their reputation

- Ensuring corporate social responsibility

- Making a profit

- Job creation

- Improving safety

- Enhancing resilience

- Reducing risk

If you don’t know who your audience is, you need to find out. There are many ways to find out including:

- Market research (desk based)

- Ask your colleagues about their audiences and contacts

- Apply for some ‘pump-priming’ or business development funding to attend industry or policy-specific conferences to learn about the audience and their motivation

4. How will you engage your stakeholders?

You will need to state how you might accelerate the route to making it happen – what specific activities are you proposing to ensure that the audience groups you have chosen will get the opportunity to benefit from your research?

Our suggested approach is:

Identify 5–6 people – key stakeholders, ideally more than half of them should be outside academia – who you might like to work with closely from the inception of idea stage (developing the proposal). They could potentially provide letters of support and/or work with you to refine the idea. Create a plan of the impact activities you will undertake during the project.

During the project, the key stakeholders might be involved from start to finish, doing anything from co-creating the research to advising on its applications in the real-world.

Once the project is underway, you could also look to engage a wider group of stakeholders who might use the research. This might involve 3–4 meetings, one at the start, one in the middle and one at the end of the research, so that you and your stakeholders go on the journey together. We would suggest you have at least four interactions with your selected audience during the life of the project to fully understand their needs, and work together on two-way exchanges to embed new ideas into both parties.

Once you have started to generate results, you might consider working with your key stakeholders to think about what types of outputs would best meet their needs and the needs of the wider group. Each output/activity should be tailored to meet the needs of your audience. We would strongly encourage you to undertake two-way engagement throughout the project, where both you and your stakeholders benefit from the interaction, rather than simply outreach or dissemination at the end of the project, when you will have no opportunity to see what any impact would be.

Any activities would be in addition to any personal academic outputs or outputs for UKRI, e.g. annual reports. All of these additional activities can be costed as part of your proposal (see Estimates for costing below).

Choosing your activities

In marketing theory and practice, there are many ways of choosing your activities. We focus on the concept we use at CREDS to illustrate our way of thinking, and as a method of choosing and structuring the activities.

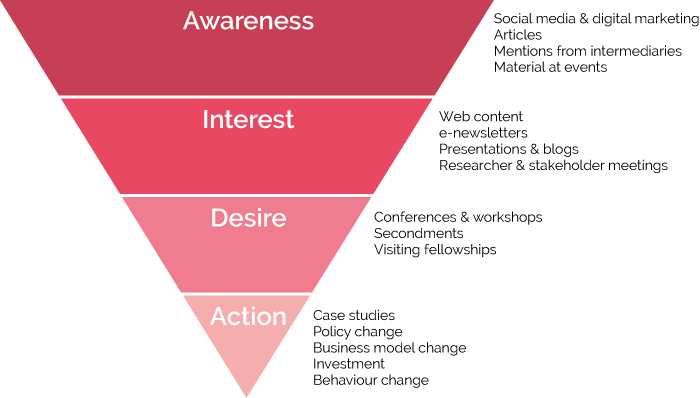

We developed the engagement funnel, based on an adapted version of the AIDA concept, as a helpful way of framing the communication and impact activities. AIDA stands for Awareness, Interest, Desire and Action. The image below (Figure 1) shows how users can be moved from ‘not being aware’ of the information about your project to ‘action’ – taking up the information and using it – but this is not an instant, single step process. This is one of many marketing assessment tools (Jobber D. 1995) that describes the stages people go through in a decision-making process and that you can use to frame your impact activities. It involves multiple interactions in an ongoing series of activities over time, to move people through the funnel towards impact via action. This is why we suggest 3–4 meetings for stakeholders during the project.

The messages used at each stage of AIDA are not the features or work packages of the project: the messages describe the benefits (e.g. new models, revised policy advice, tailored recommendations and behaviour change), and value (e.g. transforming the energy system and society) that audiences and stakeholders will get from using the information that is generated from your project.

The main message for each stage needs to be different: it should take into consideration how the message is ‘sent’ and how it is ‘received’, and where the audience is located in the AIDA framework.

You also need to engage your audience by being where your audience is – both online and physically. You need to understand: what platforms they use, what social media tools they use, what events do they attend? You need to go to wherever they are, with your main messages in engaging formats. The list on the right-hand side of the diagram gives some ideas about the different types of marketing communications tools (marcomms) and channels (online, face-to-face) that can be used at each stage – you can use combinations of these marcomms to generate your activity plan.

Our view is that the knowledge generated from research is a ‘service’. It involves multiple interactions over time to move people between each of the stages of AIDA:

- Unaware to aware

- Aware to interest

- Interest to desire and

- Desire to action.

The users start at the top with broad main messages which appeal to a wide audience and are designed to ‘raise awareness’. The messages become progressively more tailored to the individual as they move through the stages, until the final interaction that tends to be a one-to-one encounter that convinces the user to take up the information and ‘action’ it in their work or home. This may be:

- A policymaker who references your briefing in their white paper

- The NGO looking to change behaviour who uses your report in their guidance note

- A request from a different discipline for you to sit on their project advisory board.

They will all be the outcome of multiple interactions with that stakeholder.

Figure 1: AIDA stages

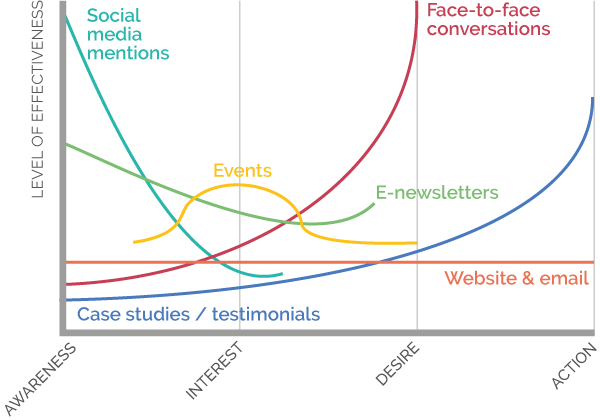

The marketing communications tools listed in Figure 1 can be displayed graphically in terms of effectiveness against the stages of AIDA (Figure 2). The graph shows that many of the marcomms tools overlap multiple stages of AIDA, demonstrating that many tools can be used at many stages, but that some tools are more effective at certain stages. You can use this graph to help plan which tools to use at which stage to create the plan, and move your stakeholders through the stages of the funnel. Each tool is defined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Graph showing where marketing and communications tools overlap multiple stages of AIDA, demonstrating that many tools can be used at many stages, but that some tools are more effective at certain stages.

Social media mentions and searches:

Google/X/Twitter/LinkedIn. A way of reaching many people in new audience types. Generates INBOUND traffic to the website to find out more, a way of increasing the audience numbers (Wikipedia/referring sites).

E-newsletter:

Creating awareness of new information (research results) or events. This covers printed media – newspapers, journals, magazines; traditional media – television and radio; and digital media – online blogs, email, website links.

Face-to-face conversations:

This used to be ‘one-to-one and small group meetings’ but is now mainly online via emails, mobile phone apps, Twitter, Facebook – anything where the information can be personalised to fit an individual’s needs or objectives. This also covers stakeholder-specific meetings that engage in dialogue, with the purpose of moving them through the funnel towards action.

Project website and individual emails:

For use at all stages with content targeted accordingly, from general to specific. Increasing numbers of people use a mobile phone or tablet to access content, so any web presence must be responsive, i.e. designed for viewing in multiple formats.

Case studies and testimonials:

Examples that show your potential new stakeholders and partners that these activities really work and it’s worth joining in.

5. Monitoring, reporting and evaluation

You need to consider how you will monitor and record your outputs, outcomes and impact so that you can justify any changes with evidence that demonstrates ‘cause and effect’.

For example, if you run a meeting, this would be considered an ‘output’, and writing a meeting or event report that includes ‘next steps’ provides the evidence you will need in order to monitor what happens next.

An ‘outcome’ is an action that emerges from the meeting, such as being asked to provide evidence to a committee a few months later. Further down the line you might achieve an impact – as a result of the meeting, your work is referenced in the report/policy white paper that is published 6 months later. Total time – 1 year. The point is that the meeting is not the impact, it is typically only after multiple interactions and some time has elapsed that impact is generated.

You may also wish to evaluate if your activities have achieved what you wanted to them to achieve. To do this it is a good idea to ask the questions:

- What worked well?

- What could be improved?

You could ask these questions internally, to your research team and externally, to your chosen short-list of stakeholders. It’s a good idea to start the monitoring and set up these evaluation processes at the beginning of the project. One suggested approach is to ask these questions quarterly to your internal team and record them. A method of approaching the external M&E is to ask the questions above in your event feedback forms, assess the answers and put the results in an event report. Six months later, schedule a short phone call that asks each respondent / or a small selection if they have used any of the information: this then begins to record ‘outcomes or uptake’. At a minimum, you should record all your outputs in a way that can be reported on Researchfish. This list of ‘outputs’ is provided in the list below.

6. Top tips

- Ask colleagues and friends about who might be interested in the results of your research.

- Attend meetings that your stakeholders might attend – industry and trade body workshops, policy-related forums and join online groups e.g. LinkedIn.

- Describe and demonstrate a clear understanding of the context and needs of users, and consider ways for the proposed research to meet their needs, or a better understanding of these needs.

- Outline the plan and management of the impact-focused activities including; scheduling (see below), personnel, skills, costs (see below), deliverables, and feasibility. Include evidence of any existing engagement with relevant end-users.

- Draft the impact sections very early in your preparation, so that it informs the design of your research.

- Leave some scope and spare time to prepare for unplanned impact during the project, so that you can benefit from unforeseen opportunities.

- Include principal and senior investigator time to work on knowledge exchange and impact activities.

- Describe the monitoring, reporting and evaluation of impact that will be carried out in the project.

There are 20 impact case studies on the CREDS website. They are mostly in the early stages, in that the majority have only generated outcomes so far. However, with further promotion they are likely to generate impact in the future.

Notes

Scheduling for activities

When planning and preparing stakeholder and impact activities, take into account:

For events:

- For example, book the date and venue 3 to 4 months in advance, prepare a draft agenda and send out invitations for events 8 to 10 weeks in advance, confirm catering numbers and dietary requirements 1 week in advance, send out reminders to attendees 1 week and again 2 days before the event.

- Discuss with PI and agree time commitment for developing the agenda, invitee list, venue, scope of meeting, facilitation and training needs of staff running the meeting, time to write an event report to capture what happened, next steps and learning

- See the Planning effective, inclusive and sustainable events guidance that includes a planning checklist.

For marketing materials:

- For example, developing a policy brief takes approximately one-week elapsed time, but more if stakeholders need to approve the text. If distributing electronically – 1 day in advance, if printing, 5 days in advance of date needed.

Estimates for costings

- 20 people meeting with tea and coffee: room hire £700 per day, drinks £5pp, other expenses e.g. flipcharts, wifi etc. (700+100+£100 = £900)

- 50 people meeting with 3 breakout rooms and lunch: room hire per day £1500, breakout rooms £400 each, lunch £20pp, drinks (1500+120000+1000+ 250 = estimate £3950).

Sub-contracting external staff

Sub-contracting enables you to bring in skills sets that may not be available within your institution.

- Consultants – junior £400 per day, senior £800 per day (7.5 hours/day)

- Journalists, technical writers, editors, photographers, designers – £300–£600 per day (7.5 hours/day)

- Producing a policy brief– 4 hrs for you to draft it, 2 hrs for editor to tailor it to the audience by adjusting the language and tone, 2 hrs for designer to layout, 4 hrs for revisions (all staff), find a place to host it e.g. website, printing costs for 200 copies = £250. Cost for 3 days of time if all internal staff, cost as above for external staff. You may need to go through a competitive invitation to tender process with 3 contractors if the total is above a certain cost threshold.

Sources of further advice on impact:

- Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) – impact toolkit.

Outputs list for Researchfish

- Publications: Record any publications, for example, journal articles, conference proceedings, reports, policy briefs, book, guide, other

- Collaborations and partnerships

- Further funding: Any additional funding & details of funding body and process, for example, research grant, fellowship, co-funding, capital, travel)

- Engagement activities: Details of activities that have engaged audiences, for example, working group, expert panel, talk, magazine, event, open day, media interaction, blog, social media, broadcast)

- Influence on policy: Details of activities that have influenced policy audiences, for example, letter to Parliament, training of policymakers, citation in guidance/policy docs, evidence to government including consultations.

- Influence on business: Details of activities that have influenced business, for example, citation in working procedures, revisions to guidance docs, citation in industry report, article in trade press, talk at trade event

- Research tools and methods

- Research databases and models: Only list the ‘new’ elements of any models, processes, data, for example, data analysis technique, handling, algorithm)

- Intellectual property and licensing: For example, copyright, patent application, trademark, open source

- Artistic and creative products: For example, image, artwork, creative writing, music score, animation, exhibition, performance

- Software and technical products: Any non-IP products that are public or do not require protection, for example, software, web application, improved technology

- Spin-outs

- Awards and recognition: For example, research prize, honorary membership, editor of journal, national honour.)

- Use of facilities and resources: For example, databases from outside of CREDS, shared facilities

- Other: Anything not already covered above.

Banner photo credit: Hannah Olinger on Unsplash