Our guidance note explains how to promote your work, and how the core team can help.

CREDS approach to promotion & how to use this document

Promoting energy demand reduction research

The core team of CREDS is focused on finding ways to present the research undertaken by the Centre to our priority audience groups, reiterating the energy demand messages that lie at the heart of CREDS (demonstrating the importance of reducing energy use as the most effective way to reach net-zero). The purpose of promoting research is to facilitate action on energy demand reduction and energy efficiency, as set out in CREDS’ aims.

Responding to external events

Promotion work is largely focused on sharing research findings from the Centre, however, we also respond to external events/occurrences to ensure our energy demand messages are heard. For example: The Clean Growth Strategy; consultation/inquiry responses; the sixth carbon budget or COP26. These provide additional opportunities for us to pull our research findings into external issues and add to the debate.

How to prepare an engagement and promotion plan for your research project

This section provides some ideas and suggestions for writing an engagement and promotion plan (E&P plan), at the start of a new project.

Section 1 This sub section explains the importance of promotion and gives you a few pointers and some questions to work through (highlighted).

Section 2 This sub section explains, in detail, what is needed for each of the questions and suggests an approach for you to follow.

By working through these questions, you will have generated some ideas about the impact your research could have and what activities you could carry out in your engagement and promotion plan to achieve the impact you want. The idea is to create a package of activities, rather than a single activity, which increases the chances that your research is seen and used.

The CREDS core team are here to help you – please ask your theme liaison if you would like advice or support with promotion.

Core team liaison contact:

- T1 Buildings | Sarah Higginson

- T2 Transport | Kay Jenkinson

- T3 Materials | Aimee Eeles

- T4 Flexibility | Sarah Higginson

- T5 Digital | Sarah Higginson

- T6 Policy | Kay Jenkinson

- T7 Heat | Clare Downing

- T8 Fair | Clare Downing

- T9 Steel | Aimee Eeles

Section 1: Why is it important to promote your research?

We want an engagement and promotion plan to improve the impact of the research you’ve undertaken. Promoting your research to and engaging with your selected stakeholders is the way to achieve impact. Promotion and engagement activities can be undertaken at different stages of the project and at each stage they will have different purposes. Engagement during the proposal stage is to raise awareness and provides an opportunity to identify partners. Bringing stakeholders in during the research stage either as partners, to jointly work together or, as advisors or, as interviewees can bring new perspectives and ideas into the research concepts. Finally, once the academic paper is written there maybe two further opportunities – one for promotion i.e. broadcasting to wider audiences to raise awareness of the findings and secondly deeper engagement with the purpose of establishing long-term relationships to do knowledge exchange.

It is expected that there will be some kind of research output, and in most cases, this is a journal or conference paper. However, this output reaches a limited, mostly academic audience that is likely to search peer-reviewed literature. It is also largely hidden behind a paywall that many outside of academia cannot access, although this is improving with pre-prints and open-access journals being more frequently used. By promoting your work, this carries the messages from your research to a wider audience that may wish to use it – more promotion means more people are aware of your research.

Promoting your research is also:

- Good for your career as it builds your CV

- Enhances your reputation, increasing the likelihood of receiving research funding

- Raises your profile leading to requests for your expertise and advice

- In most cases, the work has been funded by tax payers to benefit the ‘common good’ and we have a moral obligation to make sure our results are used for that common good.

- Improves the quality of your research by encouraging stakeholder input.

There are many ways of carrying out engagement and promotion, and each set of research results needs its own tailor-made set of activities – it cannot be a cut and paste plan.

Key questions to consider

A. Who might use the outputs of your research?

- A1. Who would be interested in the methodology?

- A2. Who would be interested in the results as they stand?

- A3. Who would be interested in the results if they were tailor-made for them?

- A4. Why would this group of people (A1 or A2 or A3) be interested in this research?

- A5. What motivates this group of people?

- A6. How could this group of people benefit from using the results of your research?

B. How can you make the impact happen?

- B1. What specific activities are you proposing to ensure that the audience groups you have chosen have the opportunity to benefit from your research?

- B2. What web platforms do these stakeholders use?

- B3. What social media tools do these stakeholders use?

- B4. What events do these stakeholders attend?

- B5. How will you monitor and record the output, outcomes and impact of your plan?

At a minimum we would expect 4 activities per set of results, for example:

- Text for a tweet via @CREDS_UK and via your own network e.g. personal and institution

- A written output for a general lay audience e.g. blog, content for the CREDS website project area

- Possibly a written output for a specific audience e.g. trade article, policy brief

- An event of some kind e.g. webinar for 50+, stakeholder workshop for ~20.

Section 2: How to approach stakeholder engagement and promotion

This section explains what is needed for each of the questions introduced in section 2.1 and suggests an approach for you to follow.

When thinking about your plan you do not need to predict exactly the impact of your research, it is more about providing suggestions about what impact you might realistically have. Impact is about who the beneficiaries of the research might be and how you are going to work with them to shorten the time between discovery and use of the knowledge. We would encourage you to think about impact at the beginning of the proposal preparation stage, then again at the start of the project, then finally once the findings are available.

The critical questions to ask yourself about your project are:

A. Who might use the outputs of your research?

B. How can you make the impact happen?

2.1 Who might use the outputs of your research?

Make a list of all those types of organisations who might use the outputs – this is also called stakeholder mapping. We suggest taking a few hours to do this – draw up an initial list, discuss it with colleagues, conduct some further market research to prioritise and finally decide on a short-list. The more specific you can be, the easier it is to develop targeted outputs for your chosen audience. The critical point is market segmentation – groups of people that have needs in common – so sub-dividing your list into smaller groups will help, as will having a particular individual in mind to represent that group.

You might like to separate them into:

A.1. Who would be interested in the methodology?

For example, researchers in other disciplines,

A.2. Who would be interested in the results as they stand?

For example, trade bodies or, policy non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or, consultants that collate information and use it for evidence reviews.

A.3. Who would be interested in the results if they were tailor-made for them?

Only using selected sections of the work and potentially taken onto the next stage by providing specific recommendations/benefits for that group, for example:

- Government – national, devolved, regional or local,

- Businesses – specific industry sub-sectors, innovative businesses, (e.g. high-use sectors), commercial, retail,

- Intermediaries – those who will pass on information to others e.g. media, trade press, trade associations, professional bodies.

For each group think about:

A.4. Why would this group of people be interested in this research?

A.5. What motivates this group of people?

A.6. How could this group of people benefit from using the results of your research?

The motivation could be the need for: personal knowledge; more detailed information; evidence to support policy; making the case for new investment; to justify a change in ways of working; maintaining their reputation; ensuring corporate social responsibility; making a profit; job

creation; improving safety; enhancing resilience.

If you don’t know who your audience is, you need to find out. There are many ways to do this, including:

- Conducting some market research (desk-based)

- Ask your colleagues about their audiences and contacts

- Apply for some ‘pump-priming’ or business development funding, or Impact Acceleration Award (IAA) funding to attend some industry or policy-specific conferences to learn about the audience and their motivation

- Ask the core team for support, working through your theme liaison.

2.2 How can you make the impact happen?

You will need to state how you might accelerate the route to making impact happen.

B.1. What specific activities are you proposing to ensure that the audience groups you have chosen have the opportunityto benefit from your research?

Our suggested approach is:

That you identify up to 10 people who will be key stakeholders (ideally more than half of them should be outside of academia) who you might like to work closely with from the inception of idea stage (developing the proposal). They could potentially provide letters of support and/or work with you to refine the idea and could form an Advisory Board.

Create a plan of the impact activities you will carry out with the key stakeholders during the project. They might be involved from start to finish, doing anything from co-creating the research to advising on its applications in the real-world – the idea is that these key stakeholders improve the quality of the research and are trusted. This might involve three–four meetings – one at the start, one in the middle and one at the end of the research so that you and your stakeholders go on the journey together.

We would suggest that you have at least four interactions with your selected stakeholders during the life of the project. This will allow for two-way engagement where both you and your stakeholders benefit from the interaction, rather than simply outreach or dissemination at the end of the project, when you will have no opportunity to learn from each other or improve the quality of the research.

Once you have begun to generate initial results, you may consider working with your key stakeholders to work out what types of outputs would best meet their needs.

This is where you also need to promote the results to a wider group who may be interested in using those results. If you are already at this stage, then the E&P plan can begin here. Each output/activity should be tailored to meet the needs of your audience.

Any activities would be in addition to any personal academic outputs, e.g. journal papers or outputs for UKRI e.g. annual reports. All of these additional activities can be costed as part of your proposal (see Estimates for costing Annex 1), and you can also apply for Impact Accelerator Awards (IAA) funding – both your institution and the project have calls and budgets for this.

Dissemination vs engagement vs knowledge exchange

We would consider dissemination as – putting a generic message out into the world, for example, on a website (from us to the world). The disadvantages of dissemination are that there is no targeting of the message nor an opportunity to engage with those that see it to get an understanding of their opinions about the research. Whereas engagement is where you are creating an opportunity for commentary, for example, via Twitter or email, and going further still through knowledge exchange. By knowledge exchange we mean a two-way exchange where both/many parties have expert, but different knowledge that can potentially be of benefit to the other. By coming to a common understanding through defining terminology and the scope of the interaction, both parties are equally valued in the exchange. An example of this type of engagement is a workshop-style event where there is extensive dialogue and potentially a joint output.

Choosing your activities

In marketing theory and practice there are many ways of choosing your activities – the toolkit. We use the concept that CREDS developed in its Communications and Engagement Strategy to illustrate a framework for thinking about the concepts, and a way of choosing and structuring the activities.

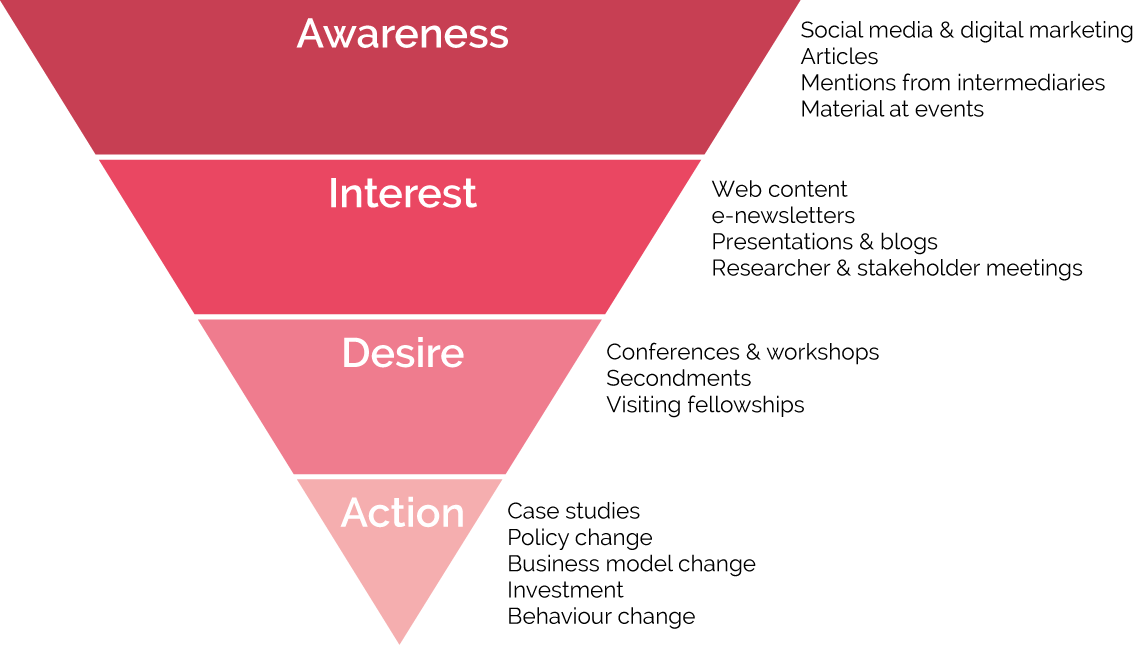

CREDS developed an engagement funnel based on an adapted version of the AIDA concept as a helpful way of framing the communications, engagement and impact activities. AIDA stands for Awareness, Interest, Desire and Action (See Annex 2). This is not an instant, single step process. It involves multiple interactions in an ongoing series of activities over time, to move people through the funnel towards impact via action. This is why we suggest three – four meetings for stakeholders during the project.

The main message for each stage needs to be different: it should take into consideration how the message is ‘sent’ and how it is ‘received’, and where the audience is located in the AIDA framework.

You also need to engage your audience by being where your audience is – both online and physically. For each of the audiences identified in A1, A2 and A3, above, you need to identify:

B.2. What web platforms do these stakeholders use?

B.3. What social media tools do these stakeholders use?

B.4. What events do these stakeholders attend?

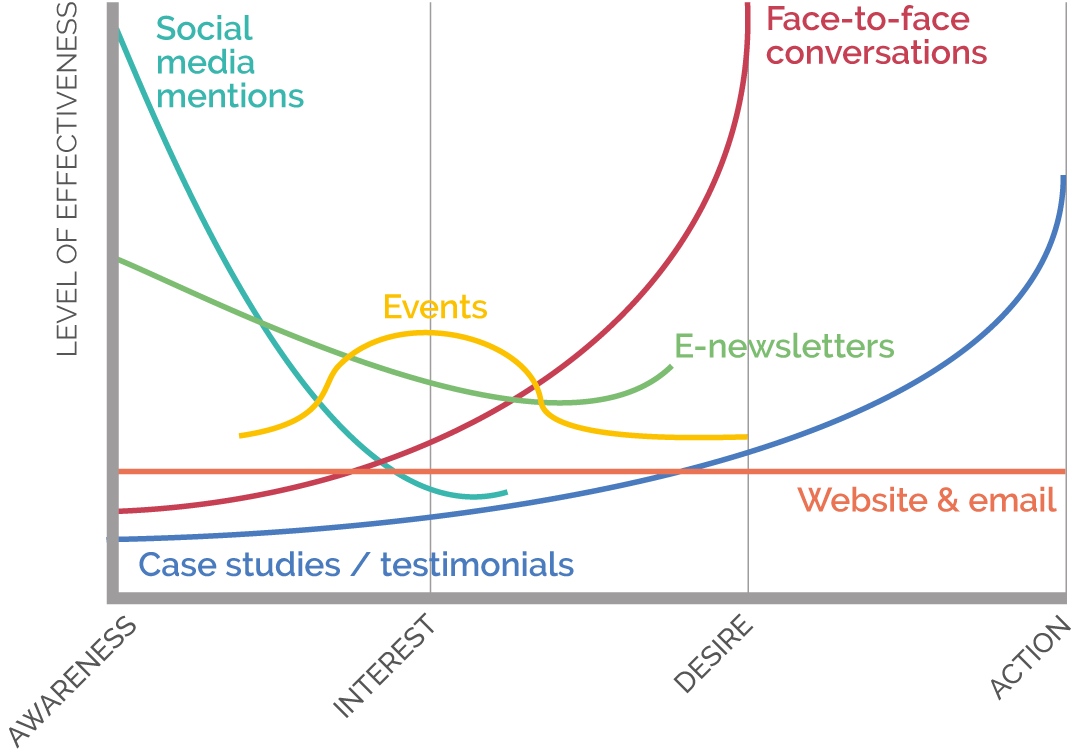

A range of different types of marketing communications tools (marcomms) and channels (online, face-to-face) that can be used at each stage are listed in Table 1. Many of the Marcomms tools can be used at many stages, but some are more effective at certain points. You can use this table (and further information in Annex 2) to help plan which tools to use to create the plan.

| Stage of Funnel in AIDA framework | Marcomms tools |

|---|---|

| Awareness | Social media – Twitter, LinkedIn,

Use of media – press, news articles Mentions from intermediaries Material at events Conferences |

| Interest | Web content – briefings, reports, blogs, case studies

e-newsletters (Consortium Update and CREDS newsletter) Presentations, webinars Researcher and stakeholder meetings |

| Desire | Workshops (face-to-face conversations -physical or virtual)

Secondments Visiting fellowships |

| Action | Case Studies

Policy advice Business model changes Investment Changes to ways of working |

The messages begin as general ones and become progressively more tailored to the individual as they move through the stages, until the final interaction which is often a one-to-one that convinces the user to take up the information and action it in their own work or role. This may be: a policymaker who references your briefing in their white paper, or an NGO looking to change their advice who uses your report in their guidance note, or a request from a different discipline for you to sit on their project advisory board. They will all be the outcome of multiple interactions with that stakeholder.

Social media mentions and searches: Google/Twitter/LinkedIn. A way of reaching many people in new audience types. Generates INBOUND traffic to the website to find out more, a way of increasing the audience numbers (Wikipedia/referring sites).

E-newsletter: creating awareness of new information (research results) or events. This covers printed media – newspapers, journals, magazines; traditional media – television and radio; and digital media – online blogs, email, website links.

Face-to-face conversations: this used to be physical one-to-one and small group meetings but is now mainly online via emails, mobile, MS teams – tools where the information can be personalised to fit an individual’s needs or objectives. This also counts as a stakeholder-specific meeting that engages in dialogue with the purpose of moving them through the funnel towards action.

Project website and individual emails: these can be used at all stages, with content targeted accordingly from general to specific. Increasing numbers of people use a mobile to access content and we have designed the website to be mobile responsive.

Case studies and testimonials: these are examples that show your potential new stakeholders and partners that these activities really work and it’s worth joining in.

2.3 Monitoring, reporting and evaluation

You will need to consider:

B5. How will you monitor and record the output, outcomes and impact of your plan?

You can use the CREDS impact spreadsheet to do this and it is available on request from credsadmin@ouce.ox.ac.uk.

For example, running a meeting would be considered an output, and by writing a meeting note/event report that includes next steps, this provides the evidence you will need to monitor what happens next. An outcome is an action that emerges from the meeting, such as being asked to provide evidence to a committee a few months later. Further down the line you might get an impact – as a result your paper/evidence is referenced in the report/policy white paper that is published six months later. Total time – one year. The meeting itself is not the impact, it is typically only after multiple interactions and some time has elapsed that impact is generated.

You may also wish to evaluate if your activities achieved what you wanted to them to achieve. To do this it is a good idea to ask your participants the following questions:

- What worked well?

- What could be improved?

You could ask these questions both internally in a wash-up meeting with your research team, and externally with your chosen short-list of stakeholders. It’s a good idea to start the monitoring and set up these evaluation processes at the beginning of the project. One suggested approach is to ask these questions quarterly to your internal team and record them. One method of carrying out external monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is to ask the questions above in your event feedback forms, assess the answers and include the results in an event report. Maybe six months later, have a short phone call that asks if they have used any of the information – this then starts to also record outcomes or uptake. As a minimum, you should record all your outputs in a way that can be reported on Researchfish. This list of outputs is provided in Annex 3.

2.4 Top tips

- Does the engagement and promotion plan take the message to them or, does it expect the reader to come to you?

- The plan should include – management of the impact-focused activities, scheduling (see Annex 1), personnel, skills, costs (see Annex 1), deliverables and feasibility. Include evidence of any existing engagement with relevant end users.

- Draft the plan very early in your project so that it informs the design of your research.

- Leave some scope and spare time to prepare for unplanned activities that might result in impact during the project, so that you can benefit from unforeseen opportunities.

- Include principal and senior investigator time to work on engagement, promotion and impact activities.

- Describe the monitoring, reporting and evaluation of the impact that will be carried out in the project and use the CREDS impact spreadsheet template.

There are some impact case studies in the CREDS annual reports (2018–2019 & 2019–2020) and many more were developed as part of the mid-term review. Some are a little immature and have only generated outcomes rather than impact so far. However, with further promotion they are likely to generate impact in the future.

Annex 1: Guidance on scheduling and costing

Scheduling

Scheduling for activities our experience and good practice suggests that the following should be considered when planning and preparing impact activities:

For events

Date and venue booked four months in advance, save the date for events sent three months in advance, agenda and invitation sent two months in advance, catering numbers and dietary requirements confirmed one week in advance, full practice run through one week in advance, reminders to attendees sent twice – one week and again two days before event.

Discussion with PI and agreement of time commitment for developing the agenda, invitee list, venue, scope of meeting, facilitation and training needs of staff running the meeting, time to write an event report to capture what happened, next steps and learning.

For marketing materials

A policy brief takes approx. one week elapsed time to produce, but more if stakeholders need to approve the text. If electronic distribution –final proof ready one day in advance, if printing five days in advance of date needed.

Estimates for costings

- 20 people meeting with tea and coffee – room hire £500 per day, drinks £5 pp, other expenses e.g. flipcharts, wifi etc. (500+100+£100 = £700)

- 50 people meeting with 3 breakout rooms and lunch – room hire per day £1200, breakout rooms £400 each, lunch £15pp, drinks (1200+800+750+ 250 = estimate £3000)

Sub-contracting external staff

- To enable you to bring in skills sets that may not be available within the university.

- Consultants – junior £400 per day, senior £800 per day (7.5 hours/day)

- Journalists, technical writers, editors, photographers, designers – £300-£600 per day (7.5 hours/day)

Producing a policy brief

- Four hrs for you to draft it

- Two hrs for editor to tailor it to the audience by adjusting the language and tone

- Four hrs for designer to layout, but allow more if there are diagrams to be redrawn

- Four hrs for revisions (all staff)

- Find a place to host it e.g. website

- Printing costs for 200 copies = £250.

- Cost for three days of time if all internal staff, cost as above for external staff and may need to do an invitation to tender potentially competitively for three contractors if over a cost

Annex 2: AIDA concept and marketing communications tools

In marketing theory and practice there are many ways of choosing your activities. We are using the concept that CREDS has used to illustrate the way of thinking and a way of choosing and structuring the activities.

CREDS has developed the engagement funnel based on an adapted version of the AIDA concept as a helpful way of framing the communications and impact activities. AIDA stands for Awareness, Interest, Desire and Action. The image below (Figure 1) shows how users can be moved from ‘not being aware’ of the information about your project to ‘action’ taking up the information and using it – but this is not an instant, single step process. This is one of many marketing assessment tools (Jobber, D. 1995) that describes the stages that people go through in a decision-making process and that we can use to frame our impact activities. It involves multiple interactions in an ongoing series of activities over time, to move people through the funnel towards impact via action. This is the reason why we have suggested three-four meetings for stakeholders during the project.

The messages that we will be using at each stage of AIDA are not the features or work packages of the project, they are the benefits (what the new models tell us, revised policy advice, tailored recommendations and behaviour change), and value (transforming the energy system and society) that our audiences and stakeholders will get out of using the information that is generated from the project.

The main message for each stage needs to be different: it should take into consideration how the message is ‘sent’ and how it is ‘received’, and where the audience is located in the AIDA framework.

We also need to engage our audience by being where our audience is – both online and physically. We need to understand: what platforms do they use, what social media tools they use, what events they attend? We need to be wherever they are with our main messages in engaging formats. The bullets on the right-hand side give some ideas about the different types of marketing communications tools and channels (online, face-to-face) that can be used at each stage and you can use combinations of these marketing communication tools (marcomms) to generate your activity plan.

We consider that the knowledge generated from research is a ‘service’. It involves multiple interactions over time to move people between each of the stages of AIDA: a. unaware to aware b. aware to interest c. interest to desire and d. desire to action. The users start at the top with broad main messages appealing to a wide audience and designed to ‘raise awareness’. The messages become progressively more tailored to the individual as they move through the stages until the final interaction that tends to be a one-to-one interaction that convinces the user to take up the information and ‘action’ it in their work or home. This may be: a policymaker that references your briefing in their white paper, or: the NGO looking to change their advice who uses your report in their guidance note, or: a request from a different discipline for you to sit on their project advisory board. They will all be the outcome of multiple interactions with that stakeholder.

Image description

An inverted triangle shows the four levels of of AIDA. First and widest level, Awareness: Social media and digital marketing, articles, mentions from intermediaries, material at events. Next, slightly narrower level, Interest: Web content, e-newsletters, presentations and blogs, researcher and stakeholder meetings. Third, smaller still level, Desire: Conferences and workshops, secondments, visiting fellowships. Final, smallest level, Action: Case studies, policy change, business model change, investment, behaviour change.

The marketing communications tools listed on the side of Figure 1 can be displayed graphically in terms of effectiveness against the stages of AIDA (Figure 2). The graph shows that many of the marcomms tools overlap multiple stages of AIDA, demonstrating that many tools can be used at many stages but that some tools are more effective at certain stages. You can use this graph to help plan which tools to use at which stage to create the plan and move your stakeholders through the stages of the funnel.

Image description

Social media mentions have a high level of effectiveness in the awareness stage. Face-to-face conversations generate a high level of effectiveness at the desire stage. Events are fairly effective at garnering interest in a piece of work. E-newsletters are moderately effective at generating awareness and can increase desire. Case studies or testimonials are mostly effective in generating action in stakeholders. The website and email are used throughout the promotion of a piece of work and maintain a steady low-level interest.

Annex 3: Outputs list for Researchfish

Publications

Record any publications (journal articles, conference proceedings, reports, policy briefs, book, guide, other)

Collaborations and partnerships

Further funding

Any additional funding & details of funding body and process (e.g. research grant, fellowship, co-funding, capital, travel)

Engagement activities

Details of activities that have engaged audiences (e.g. Working group, expert panel, talk, magazine, event, open day, media interaction, blog, social media, broadcast)

Influence on policy

Details of activities that have influenced policy audiences (e.g. Letter to Parliament, training of policymakers, citation in guidance/policy docs, evidence to government including consultations.

Influence on business

Details of activities that have influenced business (e.g. Citation in working procedures, revisions to guidance docs, citation in industry report, article in trade press, talk at trade event)

Research tools and methods

Research databases and models

Only list the ‘new’ elements of any models, processes, data (e.g. data analysis technique, handling, algorithm)

Intellectual property and licensing

(e.g. copyright, patent application, trademark, open source?)

Artistic and creative products

e.g. Image, artwork, creative writing, music score, animation, exhibition, performance)

Software and technical products

Any non-IP products that are public or do not require protection (e.g. Software, web application, improved technology)

Spin-outs

Awards and recognition

e.g. research prize, honorary membership, editor of journal, national honour.)

Use of facilities and resources

e.g. Databases from outside of CREDS, shared facilities

Other

Anything not already covered above.

Banner photo credit: Steph Ferguson