With flexibility high on energy policy agendas, Sarah Royston reviews Jacopo Torriti’s webinar on Demand Side Flexibility: Beyond price and technology.

Sarah Royston reviews Jacopo Torriti’s webinar on Demand Side Flexibility: Beyond price and technology, 02 June 2020.

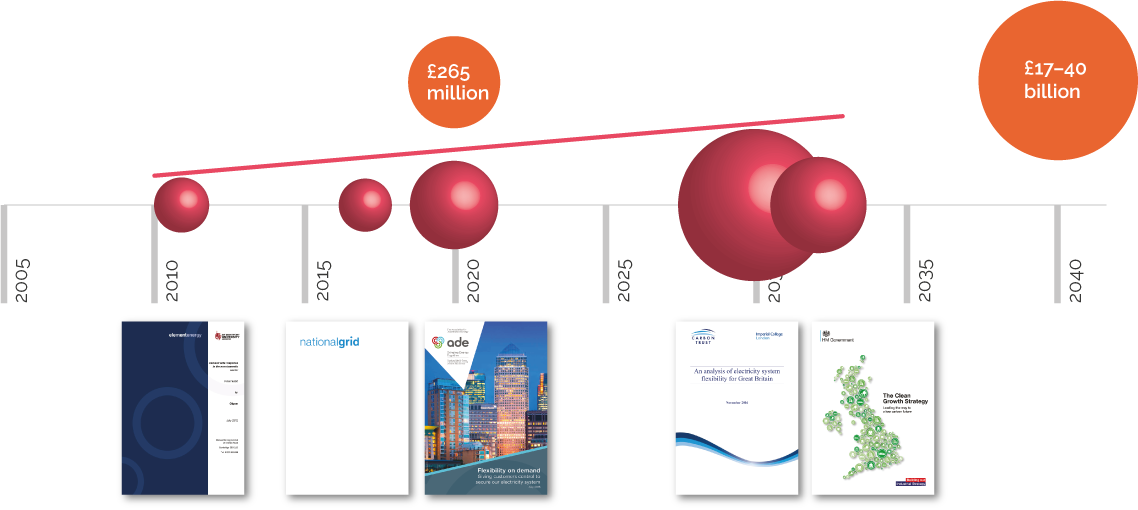

Jacopo Torriti’s webinar began with an intriguing graphic, which represents the amount of flexibility in an energy system as a more-or-less inflated sphere: the bigger the bubble, the better. If I imagine flexibility in my own daily activities that way, then lockdown has certainly burst my bubble. Everyday routines have inevitably been tightly constrained by major restrictions on how we all use space. And, like many juggling caring commitments with employment, I’m bound by newly complex temporal constraints, with each minute pre-allocated within a closely-interlocked household schedule.

As I mourn flexibilities I never previously appreciated, it seems a good moment to reflect on what flexibility means, and why it’s such an important topic for energy demand research. In this webinar, Jacopo provided a fascinating tour of core ideas and emerging findings within the CREDS research theme on Flexibility. He explained that flexibility is high on energy policy agendas, largely due to the shift towards renewable energy sources, bringing new challenges for the ‘balancing’ of supply and demand. As a result, policymakers and system engineers are increasingly concerned with defining, measuring and increasing the ‘volume’ of flexibility capacity within energy systems; seeking to inflate those bubbles.

Once imagined in this way, flexibility capacity can be given a monetary value within ‘flexibility markets’, as described in a recent paper by Jacopo’s Flexibility theme colleagues [1]. Demand-side flexibility is seen as a resource that can be developed and exploited through technological means (such as storage technologies and automated Demand Side Response) as well as through financial incentives such as Time of Use tariffs.

Beyond techno-economic framings

However, as the webinar’s title suggests, getting to grips with flexibility means thinking beyond these dominant techno-economic framings. To this end, the CREDS Flexibility theme explores not only pricing regimes and technologies, but also socio-temporal orders and practices, and how all these intersect to produce patterns of (in)flexibility that matter for energy demand. As we’d expect from the researchers involved, work within the theme draws on an exciting range of methods and data, including time use studies, electricity consumption data, agent based modelling and machine learning approaches.

One interesting project highlighted by Jacopo is led by researchers at Lancaster University, and investigates histories of fuel transitions on the Isle of Man. As other historically-engaged energy research has shown [2], examining past infrastructures, practices and service expectations can be valuable in challenging assumptions about the durability of present arrangements, and can open up new possibilities in how we envision, plan, and build for the future. To me, this kind of work also provides a crucial reminder that treating current norms as eternal is not just an academic error; if these are embedded into new flexibility policies, concrete infrastructures from domestic water tanks to power stations will be literally built on these assumptions, locking in unsustainable patterns of demand.

Another highly topical piece of work within the theme concerns the ways that flexibility interventions such as ToU tariffs are likely to affect different groups. In keeping with the theme’s emphasis on practices, this research has clustered people based on what they do during specific peak times. This analysis reveals likely winners and losers from (both current and future) flexibility policies; for example, families with children perform many energy-using activities during peak times, and could suffer under time-based payment models. As one questioner highlighted in the Q&A session, flexibility interventions raise major issues of equity and justice: will poorer and more vulnerable groups suffer enforced ‘flexing’ of their activities? Related to this, other important work in the theme looks at minimum standards for energy services in relation to flexibility, asking what uses are essential and should not be ‘flexed’.

Fundamental questions

Jacopo concluded by highlighting some fundamental questions underlying the theme’s work, including flexibility of what; and when; and for whom? I was especially interested that he asked, “Flexibility where?”. The theme’s research to date focuses largely on issues of time; for example, Blue et al. (2020) emphasise temporal issues such as synchronisation and sequencing. I wonder about the spatial dimensions of flexibility, especially the degree of rigidity/fluidity in activities’ co-locational demands, in other words: must people be present in the same place? Can it be a virtual space instead? It is little exaggeration to say that in the Covid period, such questions of co-location can be matters of life and death. And to us as energy researchers, spatial flexibility matters in all sorts of ways, including for mobility demands; for ICT-based alternatives to travel (that use energy in their construction, use and disposal); for issues of renewable prosumption (where and how much self-generated energy is used); and for the design of local and regional grid infrastructures. The spatialities of flexibility (obviously bound up with its temporalities) might offer further intriguing intersections between the Flexibility theme and its sister-themes on Transport & Mobility and Digital Society.

This webinar had particular resonance for me because of my work on the Energy-SHIFTS project, which aims to improve the impact of Social Sciences and Humanities evidence within EU policymaking on energy. Jacopo’s subtitle, “Beyond price and technology” could be applied to virtually all our outputs and communications to policymakers, as we challenge these discourses (around quantification, commodification, efficiency, predict-and-provide, behaviouralism and so on) that pervade the governance of flexibility, and every other aspect of energy systems. As Jacopo’s talk has made clear, ongoing work within the CREDS Flexibility theme serves as a showcase for this agenda, demonstrating the relevance and value of critical, socially-engaged research on energy demand.

You may also be interested in Jacopo’s article in The Conversation: Renewable energy supply and demand during lockdown – and the best time to bake bread.

References

[1] Blue, S., Shove, E., & Forman, P. (2020). Conceptualising flexibility: Challenging representations of time and society in the energy sector. Time & Society. doi 10.1177/0961463X20905479

[2] See, for example, work within the EPSRC’s DEMAND Centre.

Banner photo credit: Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash