While changes to our lifestyle are crucial, they do not often enough translate into policy. How could personal carbon budgets contribute to those changes?

Technology alone will not solve the climate crisis. In a new report, Hot or Cool Institute focuses on lifestyle changes that we need to make to come closer to 1.5°C. CREDS authors Tina Fawcett, Yael Parag (a CREDS International Visitor) and Elias Drost have contributed a chapter on personal carbon budgets.

Changes to our lifestyle are an integral part of the climate discourse, especially in high-income countries. However, they do not often enough translate into policy. Instead, many investments or policies still incentivise high-carbon behaviour and consumption. The newly launched 1.5-Degree Lifestyles report sheds light on the key role of lifestyle changes in reducing greenhouse gases. It is complementary to the recent CREDS positive low energy futures work,which showed that the UK could halve its energy demand by 2050.

How do lifestyles matter?

The report analyses the carbon footprints of ten countries and identifies emissions reduction gaps: More than 90% of emissions need to be cut until 2050 if these countries are to stay within their 1.5°C degree-budget. These cuts do need to come from technological innovation, but to an important extent also from changes to how everyone lives, moves, and consumes. Scenarios in which countries meet their 2030 targets reveal the urgency of such lifestyle changes: High-income countries will not be able to reach their targets without adopting an amazing number of consumption and behaviour changes.

A way to encourage change

Acknowledging both urgency and extent of necessary policies, the report presents some radical, non-mainstream options which could help bring about these changes. One of them is carbon rationing, a section that we contributed. The term “rationing” might carry the connotation of war time and emergency, linking it to food rationing, for example, during the Second World War. Putting limits on how much meat, cheese, fats, or sugar an individual could buy served the double purpose of preventing overexploitation of the scarce resource food and ensured equal access for everyone.

Today still, various rationing policies serve the same purpose. During the winter storms in Texas, USA earlier this year, authorities cut off the power where the grid was damaged to avoid wide scale blackouts. In Cape Town, South Africa, water use was restricted during the severe drought in 2018. Rationing is part of the toolbox available to today’s policy makers. With some imagination, this idea can be applied to greenhouse gas emissions: To preserve a clean atmosphere, the right to pollute must become scarce and rationed.

How to ration carbon

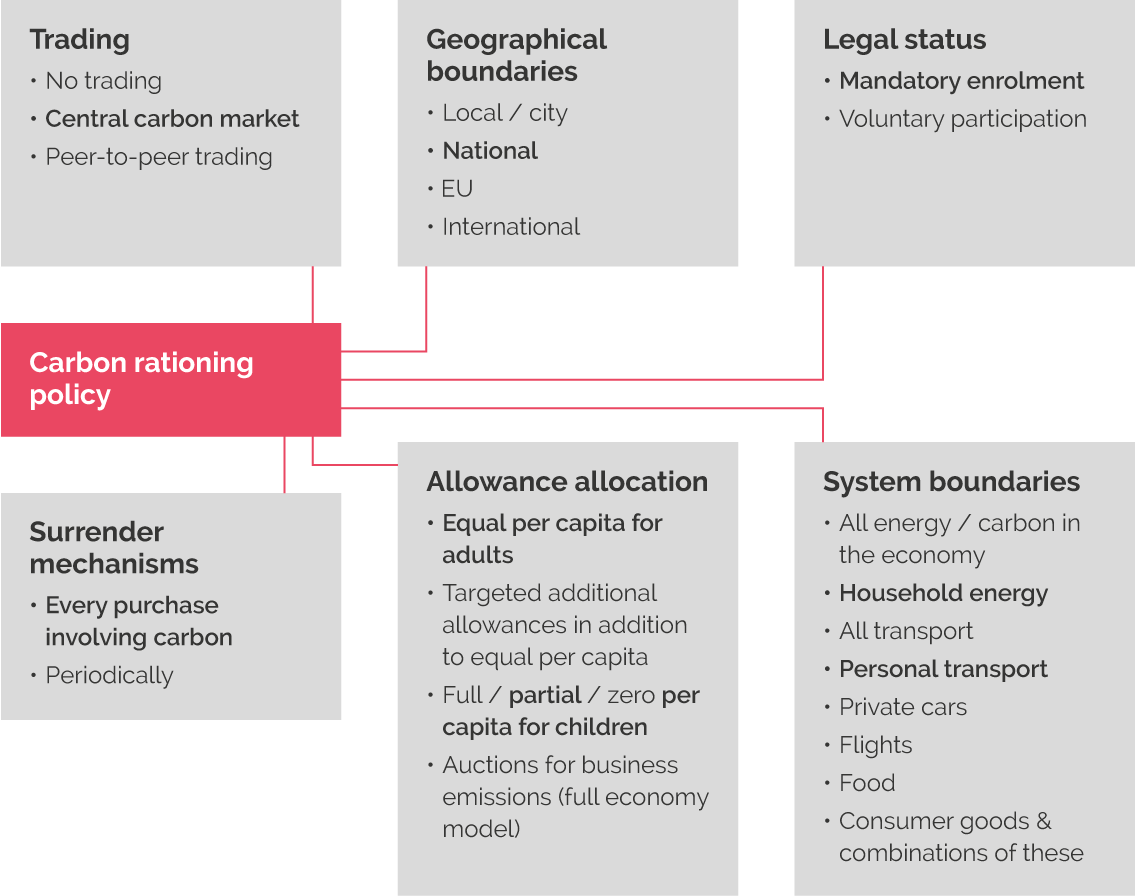

There are a number of concrete policy proposals how to do this. Their differences revolve around six questions (see Figure): What geographical area is covered by the rationing scheme? What type of emissions are rationed? Is participation in the scheme mandatory? Who gets how many rations? Can rations be traded among participants? How are rations surrendered? One of the more detailed proposals is a scheme called Personal Carbon Allowances. It operates on a mandatory, national basis and covers emissions from household energy, typically gas and electricity, as well personal transport. Every adult gets an equal amount of rations, children a share of that, and trading is allowed among individuals.

Image text

Carbon rationing policy elements: Trading – No trading, Central carbon market (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), Peer-to-peer trading; Geographical boundaries – Local / city, National (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), EU, International; Legal status – Mandatory enrolment (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), Voluntary participation; Surrender mechanisms – Every purchase involving carbon (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), Periodically; Allowance allocation – Equal per capita for adults (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), Targeted additional allowances in addition to equal per capita, Full / partial (Personal Carbon Allowances policy) / zero per capita for children, Auctions for business emissions in a full economy model; System boundaries – All energy / carbon in the economy; Household energy (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), All transport, Personal transport (Personal Carbon Allowances policy), Private cars, Flights, Food, Consumer goods & combinations of these.

Why trading?

Allowing trading of rations for money acknowledges that individuals have hugely different personal carbon footprints. How much emissions a person causes depends on where they live, what heating fuels are available to them, or what kind of house they live in, but also on their consumption choices. If an equal, inflexible ration were imposed on everyone, this would either impose grim restrictions on a large fraction of over-emitters immediately, or it would require rations so large that their effect would be insufficient. Trading allows different actual consumption levels while staying within an overall cap.

We need to talk…

Nonetheless, carbon rationing as a policy idea is controversial. It would create winners – below-average emitters – as well as losers in the group of those emitting more than the average. This is especially of concern for those who would lose money through rationing, but do not have the means to invest in a lower carbon lifestyle. Beyond that, implementation and cost of a rationing scheme are policy concerns as well as support for it among the public. For a potential rationing policy to be acceptable for a majority, discussions are necessary including policymakers, experts, and citizens. Citizen assemblies in several countries have proven to be a useful opportunity to engage stakeholders within the climate policy debate. Talking about urgent lifestyle changes is useful, if not a prerequisite for change-inducing policy to be effective.

Banner photo credit: Tim Bechervaise on Unsplash