Cost-reflective tariff structures would help address excessive energy consumption. But what do we consider excessive energy consumption to be? Latest blog from Jose Luis explores.

In this year’s edition of the ECEEE Summer Study, we presented a paper which had the aim of conceptualising what we refer to as Core power capacity requirements, as well as to provide some estimates of what these might look like based on the analysis of empirical power demand data.

But before we jump into the specifics of what these might be, it would be good to provide a bit more context about the broader problem we’re trying to address.

In general, peaks in energy demand tend to be quite costly – both in economic and environmental terms.

Given current social and institutional conventions, some peaks are inevitable. However, not everything that happens during these peak periods ought to happen then and there.

In principle, more cost-reflective tariff structures would help in addressing these issues, by discouraging excessive consumption.

But in order to develop such new tariffs, we need to first determine what we consider as excessive and what different types of consumers should be entitled to based on their circumstances.

No one-size-fits-all solutions

Electric power has become an essential part of our lives; it is what makes possible many – if not all – of those things we do as part of what we consider a good lifestyle.

In the Global North, power is virtually everywhere.

But one size does NOT fit all.

If everyone had the same, or very similar requirements, we would see – statistically speaking – much less diversity, and the distribution of energy requirements would look very much like a typical bell curve with low variance.

But, is that really the case?

Well, it turns out that the distribution of energy requirements in the UK residential sector is much more complex than the typical normal distribution.

And in a previous study of the diversity of residential annual energy requirements in the UK it was found that the overall distribution was roughly made up of three main clusters.

And while a more or less homogeneous range of energy requirements would entail a linear relationship between increases in demand for energy and the size of a household – meaning that the more people, the more energy is required – a more detailed breakdown of the different clusters reveals that this is far from being the case.

Thus, when it comes to defining what is an acceptable level of demand for energy and what isn’t, we need to make sure that the more disadvantaged groups are not being charged more than they need to, and effectively subsidising those who are better off.

So, essentially, we need to make sure to identify the range of sizes that allow everyone to have access to the same capabilities.

And here is where the conceptual framework known as the Capabilities approach comes in handy when conceptualising Core power capacity requirements.

The Capabilities framework

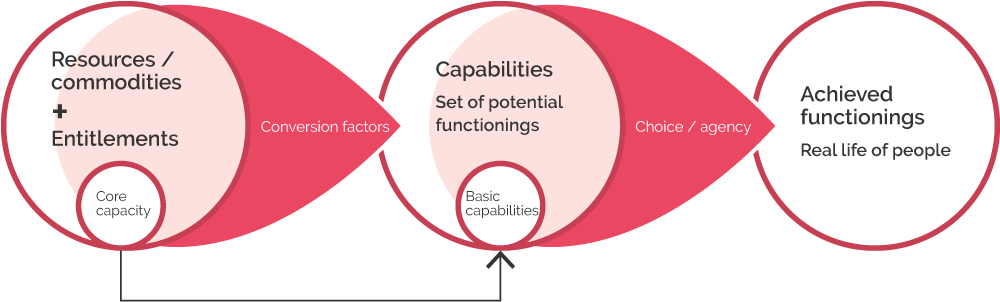

The Capabilities framework is based on 3 key concepts:

- Functionings: The different ways of doing things – most of which require some kind of energy or energy service

- Capabilities: which are the set of Functionings people are able to achieve

- Conversion factors: which are the varying abilities of different groups of people to transform material resources and commodities into objective well-being.

So how does this relate to energy consumption?

Well, here is where the concept of Core capacity comes into play.

In a nutshell, the core – or rather, the set of core levels of power capacity provision are what enable the Set of basic capabilities.

However, in order to adapt the Capabilities framework to the context of Energy research and the study of energy demand, we need to unpack this connection further.

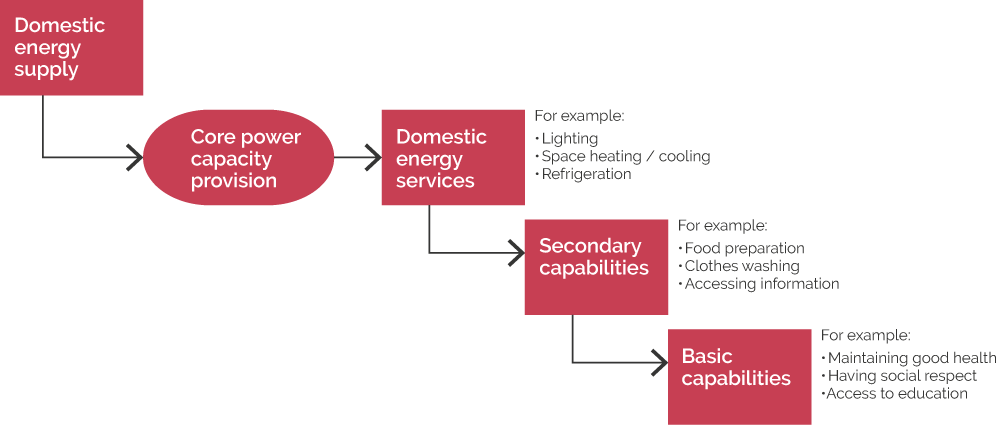

In the context of the Capabilities framework, energy is part of the set of material pre-requisites – or means – to the realisation of certain capabilities – which are the ends.

In that sense, Core capacity can be understood as the level of energy service provision that allows for an adequate access to basic energy services, which in turn enable the attainment of secondary capabilities such as food preparation, which are a preamble to the attainment of basic capabilities such as maintaining good health.

But again, the connection between Capabilities and Functionings, is not a straight line.

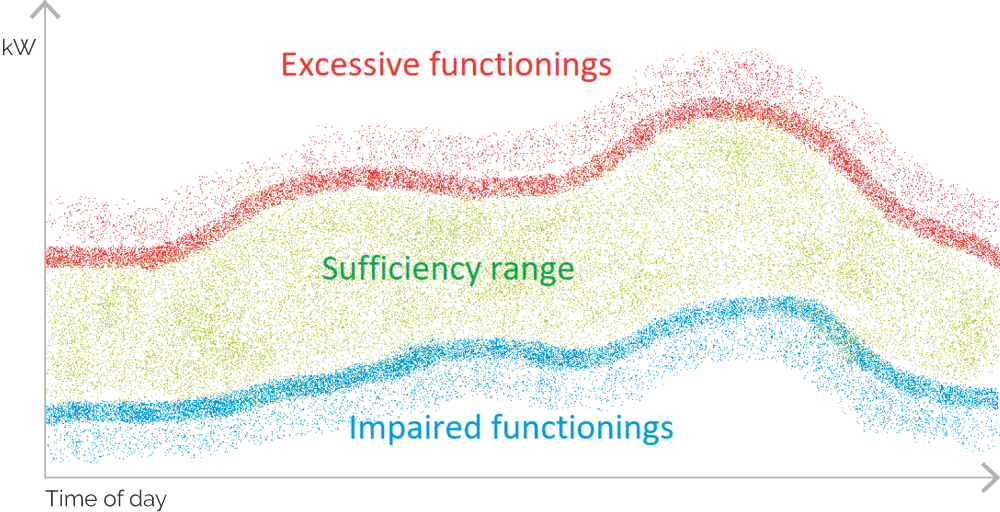

Those Functionings, or “ways” of doing “things” can fall into “the sufficiency space” or they can fall into the excessive consumption range, when, for instance, someone is keeping the indoor home temperature at 25°C during winter so that they can dance in their underwear.

What appears to be sufficient for most people, over most days, over a number of years…

So, it is precisely this sufficiency range that we are interested in, and with that aim in mind, we looked into what appears to be sufficient, for most people, over most days, over a number of years, based on empirical energy demand data for over 20,000 households monitored as part of different studies, in order to provide preliminary estimates of what the set of cores of power capacity provision looks like.

Overall, based on the largest sample of households, it would appear that the upper threshold of this range of Core capacity is somewhere between 2 and 3 kW.

However, a more detailed breakdown shows that there is considerable variability across the sample when this is calculated, for instance, based on income, or based on whether they are located in urban or rural settings.

The road ahead

So, in conclusion, the results of this preliminary analysis highlight the following:

- Diversity matters

The upper thresholds of the core capacity requirements associated with different sectors of the residential consumer population range from about 2 kW to about 7 kW for those who rely on electric power to provide thermal comfort. - Conversion factors matter

The fact that a positive correlation between affluence levels and core capacity requirements was observed, would appear to indicate that the different Conversion Factors have a significant influence which might need to be studied in more detail. - National averages are not enough

Because of the same reason, we can confidently say that top-down studies based on national averages are just not enough, and more nuanced views on what is required to achieve the same or similar levels of well-being across different sectors of the population are needed in order to determine what constitutes excessive consumption. - No black & white solutions

The differences across different datasets provide clear evidence of the fact that there are no Black & White solutions, and that the boundaries between what is and isn’t essential are and will likely remain fuzzy. - Still lots more to be done

And finally, it is clear that there is much more to be done when it comes to fully unpacking the relation between energy consumption and well-being. But hopefully, in the near future, we will be able to carry out much more detailed studies of the different energy services people have access to, and how much energy is required in order to enable specific capabilities.

Banner photo credit: