Two home living exhibitions were recently visited by CREDS researchers. Energy was not featured explicitly in either exhibition – a challenge to CREDS and the wider research community to ensure that future exhibitions about buildings and people take energy and materials use more seriously.

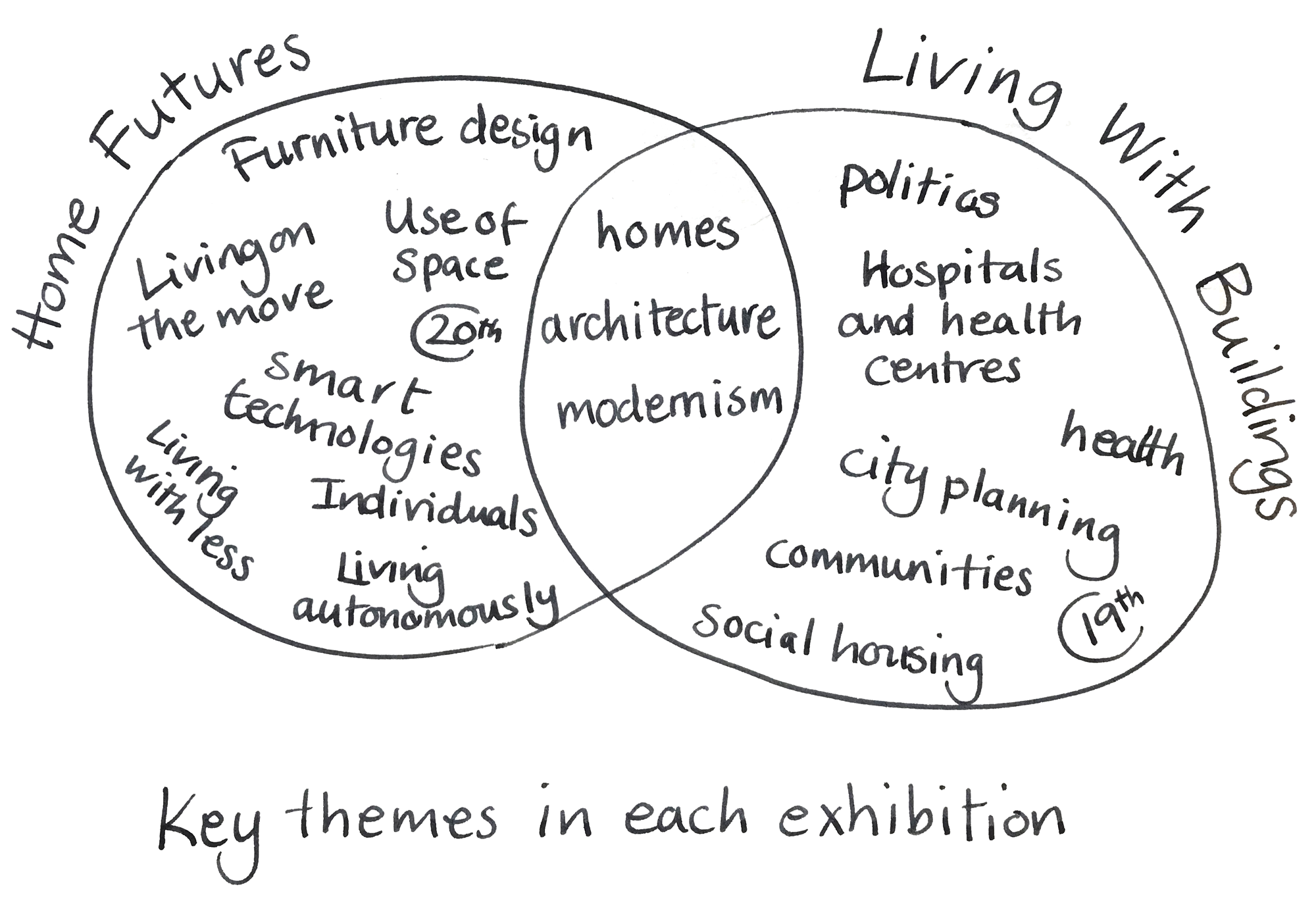

CREDS researchers recently visited two exhibitions in London. The first was Home Futures: Living in yesterday’s tomorrow at the Design Museum. The second was the Wellcome Trust’s Living with buildings: Health and architecture. These exhibitions both considered aspects of buildings’ architecture and its influence on people – but from quite different perspectives (as illustrated below).

Our aim in visiting these exhibitions was firstly to see whether and how energy and the embodied energy of material/technology use were considered either explicitly or implicitly. We also wished to learn from and reflect on their content, in relation to the CREDS work agenda, and specifically linking to our research on buildings renovation and changing behaviours and practices.

Home Futures was fascinating. It presented twentieth century ideas about how we might live in the future, and questioned whether technology has radically changed the indoor ‘microenvironment’ and the way we live today. Utopian visions of future homes embodied radical ideas in architecture and illustrated their implications; many from the Italian movement of theorists from the 1950s onwards. From Ugo La Pietra’s research and experimentation in the early 1960s, to Ettore Sottsass, the exhibition had a strong sense of houses as an indoor space/shelter in which human senses evolve through peoples’ activities and interaction with conventional or futuristic objects. In these utopian futures, the materiality of the building itself has not changed but the ‘senses’ that the indoor environment creates have.

The futures illustrated included movable and modular homes, movable walls, multipurpose and small living spaces, surveillance and screens, and automatic home appliances. Some these ideas have become realities, other still seem futuristic – utopian or dystopian, depending on your point of view. One of the exhibition themes was ‘living smart’, showing previous dreams of the technologically enhanced home, including a robot vacuum cleaner from 1959. Playful art works suggested that smart technology makes demands on homes and requires people’s time: although it may be invisible, it has its own space within a home.

Architectural philosophies across time were explored – from Mies van der Rohe’s 1920s beliefs of “less is more” and “God is in the details” to Pier Vittorio Aureli’s “less is enough” in 2014. Finally, a number of commentators reflected on today’s visions of future homes. These included ideas around constant mobility, sharing of homes, technological futures, reductions of space and possessions, and even the end of the idea of home. The radical nature of these ideas contrasted with the notably conventional homes in which some of the contributors were filmed.

Living with Buildings focused less on individual experiences of living in buildings, and more on buildings within and for communities. The exhibition examined some of the ways in which architecture and the built environment interacts with concerns of health and wellbeing. As well as a history of health and housing from the nineteenth century onwards, it also looked at the architecture of hospitals and health facilities, finishing with the first complete version of a ‘Global Clinic’. This was new design, made from plywood, which could deliver a flexible, robust and easy to transport and build space for emergency health care.

Energy was not featured explicitly in either exhibition. There was a strand about people using less space and living well with less in Home Futures. However, this topic was introduced as an architectural and design challenge given economic constraints, not for environmental reasons. In Living with Buildings, refurbishment of buildings and comfort was considered to a greater extent – but again, there was no focus on energy use, the role of energy in buildings or mitigation and / or adaptation to climate change. This was perhaps an important reminder that other people do not see the world in the same way as us. It is also a challenge to CREDS and the wider research community – to ensure that future exhibitions about buildings and people take energy and materials use more seriously.

Banner photo credit: Nathaniel Villaire on Unsplash