Why do people heat their homes the way they do, and what are the underlying patterns behind personal heating preferences and practices?

Home heating is essential through any blustery British winter, especially as Covid-19 restrictions confine us to our own living spaces and deepen our appreciation of home comforts. Accounting for 37% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, the heating sector also forms a large part of the national decarbonisation puzzle.

A new research paper involving Sussex Energy Group researchers, Humanizing heat as a service: Cost, creature comforts and the diversity of smart heating practices in the United Kingdom, looks at why people heat their homes the way they do, and the underlying patterns behind personal heating preferences and practices. This blog explains some of the paper’s findings – exploring the breadth of motivations to heating decisions, the many needs heat meets, and how its application isn’t always exclusively for the benefit of human residents.

Introducing energy phenomenology

‘Energy phenomenology’ is the paper’s proposed means of understanding people’s heating choices. It combines the lived experience approach with energy biographies to form a framework for understanding how experiences, practices and identities shape energy services and consumption.

The lived experience approach studies individual’s unique human actions and behaviour along with the subjective meanings associated with life events. It describes emotions and non-rational elements of behaviour not captured by many other modes of inquiry, including stated preference techniques.

Energy biographies interrogate how energy use expresses shared practices and attaches meaning to everyday behaviours which can often be taken for granted.

The paper combines both approaches to form “the energy phenomenology framework”.

Identity shapes heating use. Seeing yourself as an environmentalist or consumerist, a parent or a child, wealthy or poor, will influence energy consumption. These identities and their associated values and priorities with domestic niceties like a warm home, a clean bathroom, a comfortable living room, or a convenient way of doing a chore will shape consumption.

Historically shared practices, routines, habits, and norms can fuse together with infrastructure such as appliances, gas boilers, or buildings to lead to socio-material attachment. Heat practices are also dynamic and temporally complex, altering and changing across life events and stages, a process we term lifestyle changes.

Parenting, preening, pets and pipes: what motivates heating decisions?

Researchers applied the energy phenomenology framework to experiential data gathered through the Energy Systems Catapult’s Living Lab, which provided 100 homes across Birmingham, Bridgend, Manchester and Newcastle with smart heating and digitally operable zonal heating controls.

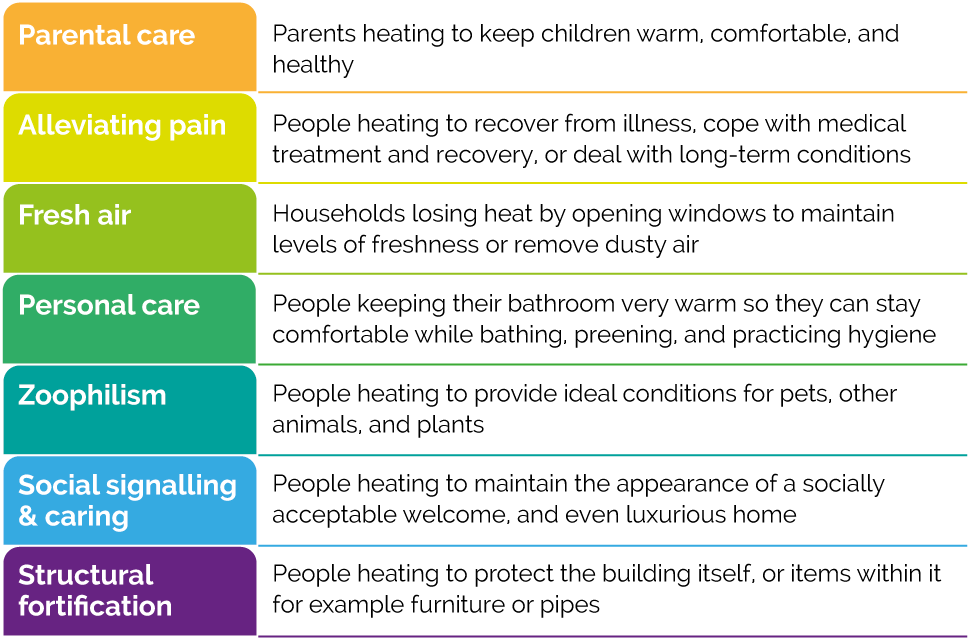

Data collected through interviews and diaries produced hundreds of pages of qualitative data, within which researchers identified seven distinct themes recurring in participants’ energy usage.

One of the most prominent themes is heat’s versatile application to provide care and compassion through adjusting a thermostat. Residents used heating to anticipate children’s discomfort, soothe arthritic joints, and relieve symptoms of illnesses or their treatments. This application of care is often extended to non-human household members, with residents recording how they would leave heating on for pets, and even houseplants, when leaving their homes otherwise empty.

Once the wellbeing and comfort of the inhabitants had been assured, residents often applied heat to the needs of the building that house them. Several households explained how their use of smart heat intended to prevent structural damp and protect pipework from the possibility of freezing.

It’s important to keep the building warm, you know? We haven’t got damp and one of the reasons is presumably because we’ve got the heating on.

Social signalling can also be an element behind heating decisions, projecting comfort and hospitality. What host could pass up the opportunity to bask in the approval of their well-toasted guests, as well as the warmth of their hardworking boiler?

I want a home that is warm, comfortable, family friendly, and homely. That’s what heat is for.

Identity, needs, attachment and transition – what lies behind heating motivations?

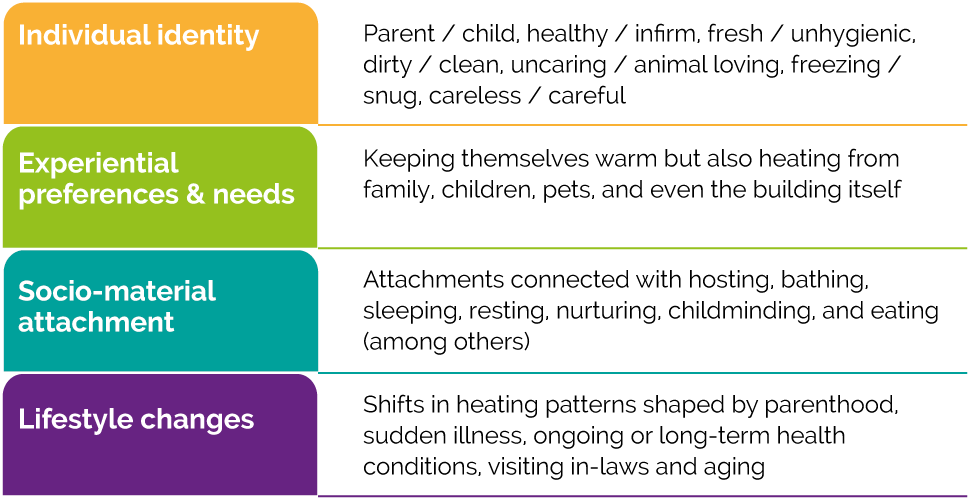

How can the functional uses of heating, as used by the Living Lab’s residents, be placed within the energy phenomenology of smart heat? The paper puts forward four influences behind the motivations for heating decisions.

Individual identity. Heat controls provide an outlet for the roles an individual assumes. Heating practices help to communicate that sense of being a nurturing parent or caregiver, or conscientious homeowner. They can even replicate rituals from childhood, with one resident keen to provide their son with heated pyjamas despite his equally heated opposition.

I used to like it when I was little, so I have passed it along to him. Sometimes he whines, and says, ‘It’s too hot, it’s too hot,’ but it’s better than having a cold pair of pyjamas, isn’t it, really?

Experiential preferences and needs. The diary entries reveal how many needs can be met through the calibration of a virtual thermostat. The paper’s most memorable example comes in the unexpected form of a cat’s birthday party, where the host’s pet-loving instincts combine with social signalling and expressions of care for elderly houseguests.

When people come over, we want to make sure the house is warm. Especially if there is something special going on, like it being the cat’s birthday or something crazy like that. We just have a party for anything. Any excuse for a party. So when I am roasting a dinner on a Sunday or something, and then we had an excuse for a cake and stuff, people will come over. And some of our friends are old, or disabled, so we need to keep it always really warm for them.

Socio-material attachment. Domestic habits are often shaped by a mix of personal behaviours and ingrained behaviours formed in response to an inhabitant’s surrounding infrastructure. Smart heating proved to be no exception to this. Several residents used smart heating controls to indulge a fond concept of the bathroom as “a special room” for self-confessed extravagance. Some residents use their controls to give it “an extra boost” before use, with one even leaving theirs perpetually heated. These attachments can be more sustainable (e.g. letting rooms cool before sleeping) or less sustainable (e.g. always keeping the bathroom warm). Either way, but they are a considerable factor in heating usage.

Lifestyle changes. Heating needs and experiences shift over time and as lifestyles change. Hallmarks of adult life, such as hosting guests and raising children, can give way to managing long-term illnesses and increasing sensitivity to temperatures with age. These shifts demonstrate the changing nature of heat and offer promising opportunities for predicting and improving heat management.

Humanising heat research and policy

What does energy phenomenology’s perspective of these themes and motivations mean for how we understand heating use? This research highlights that “for occupants, heating preferences must be discovered through a process of learning, engagement and living, rather than existing as something innate or predetermined, or known in advance”. Heating users may not recognise their own heating preferences and expectations without the degree of immersive involvement facilitated by initiatives like the Living Lab.

This means stated preferences, as often derived from surveys and similar research tools, acquire only an insufficient understanding of the topic. Instead, revealed preferences can allow policymakers and planners to account for the diversity, irrationality and unpredictability of heating practices shown in the study.

The paper contrasts the arguably more successful efforts to decarbonise transport, with policy approaches to decarbonise heating. Policy developments in heat have encouraged increased efficiency and encouraged the adoption of low carbon heating systems. However, with this and other studies clearly illustrating the value of heat for a multitude of other purposes, the industry could learn from carmakers’ talent for meeting consumer needs along a range of price points. Luxury home comfort items meeting similar needs, like electric powered “fire”places, have become increasingly popular. These products point to an untapped potential to capture some of the glamour and momentum of carmakers like Tesla, the principles behind their success selling a vision of “luxurious forms of electric mobility” applied to the mundane world of boilers and radiators.

Whether it’s warming pyjamas, impressing guests, comforting the elderly or bathing in extravagantly humid bathrooms, heat and its human (and often humane) application reflect the diversity of human experience and identity. Researchers, policymakers, planners and even smart heat technologists can benefit from greater insights into how these easily overlooked factors work for and against decarbonisation objectives.

First published by the University of Sussex.

Parental care: Parents heating to keep children warm, comfortable, and healthy. Alleviating pain: People heating to recover from illness, cope with medical treatment and recovery, or deal with long-term conditions. Fresh air: Households losing heat by opening windows to maintain levels of freshness or remove dusty air. Personal care: People keeping their bathroom very warm so they can stay comfortable while bathing, preening, and practicing hygiene. Zoophilism: People heating to provide ideal conditions for pets, other animals, and plants. Social signalling & caring: People heating to maintain the appearance of a socially acceptable welcome, and even luxurious home. Structural fortification: People heating to protect the building itself, or items within it for example furniture or pipes.

Individual identity: Parent / child, healthy / infirm, fresh / unhygienic, dirty / clean, uncaring / animal loving, freezing / snug, careless / careful. Experiential preferences & needs: Keeping themselves warm but also heating from family, children, pets, and even the building itself. Socio-material attachment: Attachments connected with hosting, bathing, sleeping, resting, nurturing, childminding, and eating (among others). Lifestyle changes: Shifts in heating patterns shaped by parenthood, sudden illness, ongoing or long-term health conditions, visiting in-laws and aging.

Banner photo credit: Alexander Raths on Adobe Stock