Sarah Higginson and Gesche Huebner

Summary

CREDS is a UKRI Energy Programme focused on the critical role of energy demand in reducing carbon emissions and achieving the UK’s net-zero carbon ambitions. As part its funding from UKRI, CREDS has a Flexible Fund to fill research gaps and develop research capacity. The call for Early Career Researcher-led projects was the largest single use of the Flexible Fund, with £1M (at 80% FEC) being allocated to it.

As this call was for Early Career Researchers, additional support mechanisms were put in place during the call itself and a comprehensive programme of feedback has followed the call. In order to assess the effectiveness of this, a thorough evaluation was conducted looking at the call itself, its process and various aspects of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) involved in the call. This report outlines the results.

The evaluation concludes that the call was basically successful, well-run and well received. The support offered was, for the most part, enthusiastically taken up and well regarded. The qualification criteria for being an ECR, of not having held a grant as PI in excess of 100 K, alongside allowing people on non-permanent contracts to apply, were important in encouraging applicants who are not normally eligible. It is also clear that more funding for ECRs would be very welcome, potentially increasing the diversity of our research community. Based on the success of our programme, ECR funding represents a small risk from a public investment point of view.

To make the most of further funding, additional training, mentoring and support would be helpful, particularly for ECRs. Targeted, rather than generalised, support is more useful. We recommend experimenting with a system where those who are funded ‘pay it forward’ by supporting others who are looking for funding, to help manage the resource implications. Actual resources need also be allocated, however, to deliver the potential benefits of such a scheme.

Our main learning was that feedback to applicants is crucial. Feedback should be routinely provided to applicants and put into context by sharing reviewers’ comments and success rates. We recommend a better feedback framework to help reviewers make the most of the opportunity to provide constructive, relevant feedback to applicants. We would also encourage experimentation with funding models as the current one, with its up to 90% failure rate is very wasteful of people and resources.

The call performed well in terms of EDI, which was monitored throughout the process and formed an important part of the evaluation. A significant number of awardees and applicants have caring responsibilities and only about a third have a permanent academic post. In terms of gender, ethnicity and disability, the CREDS call performed slightly better than ESRC and significantly better than EPSRC, though this is partly a function of ECRs being a more junior, and therefore generally more diverse, group.

We have a number of recommendations in relation to diversity. We propose that publicly funded programmes should all have mechanisms in place to monitor and increase the diversity of applicants. Monitoring the diversity of reviewers, panels, applicants and awardees of funding programmes is also important. Attending to the language of calls to eradicate gendered or otherwise biased language and paying attention to interdisciplinarity can also can also contribute to increasing diversity.

The advantage of programme-based funding from centres like CREDS is that those funded are immediately immersed in a community of like-minded researchers. However, the resource implications are significant (with attendant research opportunity cost implications) and there is clearly a potential for programmes to make errors as there are few guidelines to support ‘decentralised’ funding calls. We have recommended that such programme-based funding be properly evaluated and its lessons shared. We will be sharing our lessons with other similar consortia. We have also recommended that funding processes be evaluated as to whether they are producing the desired results, not just in terms of research outcomes but also in terms of retaining people in academia, enhancing the diversity of our community and producing research relevant to our society.

We would like to congratulate the ECRs joining CREDS and look forward to benefitting from their exciting contributions. We would also like to thank all those involved in the funding call, including applicants, reviewers, the panel, the CREDS core team and those who were involved in the evaluation.

1. Introduction

1.1 What is CREDS?

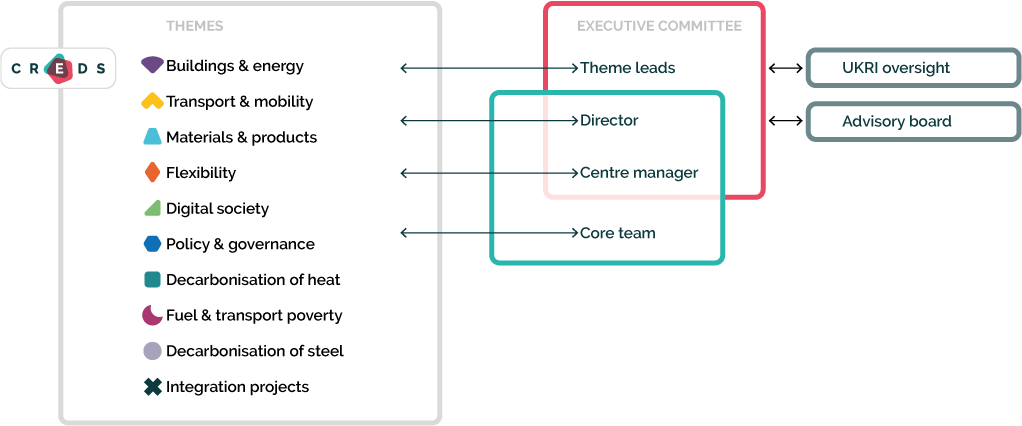

CREDS is a UKRI Energy Programme funded, from April 2018 to March 2023, with a budget of £19.5 million. CREDS’ research recognises the critical role of energy demand in reducing carbon emissions and achieving the UK’s net-zero carbon ambitions. It is a distributed centre, involving 20 universities working across 9 themes (see Figure 1), with a core team based at the University of Oxford. The themes are:

- Sectoral: Materials and Products, Transport and Mobility, Buildings and Energy

- Cross-cutting: Policy and Governance, Digital Society, Flexibility

- Decarbonisation challenges: Decarbonisation of Heat, Decarbonisation of Steel, Fuel and Transport Poverty

Figure 1: CREDS structure.

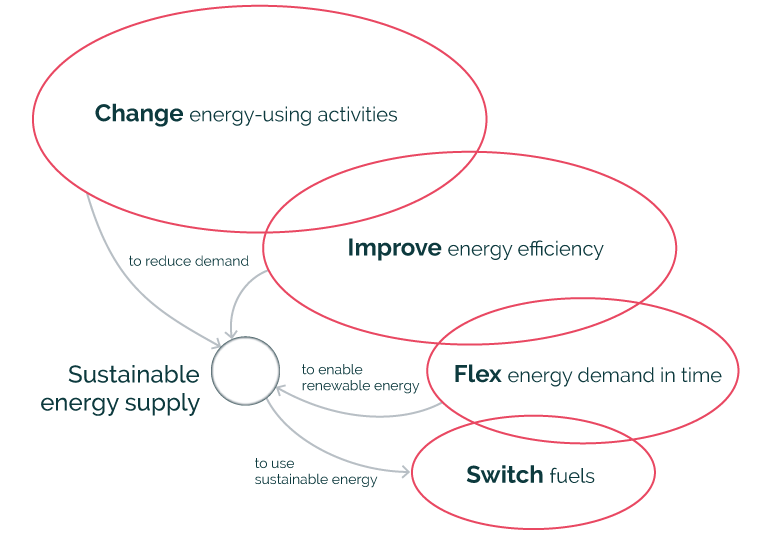

The challenge for energy demand in future energy systems is to reduce energy demand especially for heat and transport; to flex energy demand to make use of variable renewables and to decarbonise heat and transport, largely by fuel switching to low- and zero-carbon electricity, all in the context of other changes, notably decentralisation, digitisation and the UK’s net-zero carbon ambition.

Figure 2: Changes to energy demand in the zero-carbon transition.

Our ambition is to be a hub for UK energy demand research, creating knowledge for businesses and policymakers, and to deliver a transformational programme that champions the importance of energy demand, securing greater attention from opinion formers.

1.2 Description of the CREDS Early Career Flexible Fund Call Process

1.2.1 The call

As part of the CREDS funding from UKRI, CREDS has a Flexible Fund to fill research gaps and develop research capacity. The call for Early Career Researcher-led projects was the largest single use of the Flexible Fund, with £1M (at 80% FEC) being allocated.

The call was restricted to supporting projects led by early career researchers (ECRs). In this case, this was defined as people active in energy research in the UK who had not previously led a project as PI with funding exceeding £100k.

Full guidance on the call and how to apply were published on 25 July 2019. The scope of the call allowed for a broad definition of ‘energy demand research’. There was encouragement to submit small projects, i.e. costing less than £20k, through a requirement for less detailed applications. Applications were particularly encouraged from members of groups under-represented in the UK energy research community.

The call was promoted widely, including through the CREDS newsletter and website, UKRI newsletter and website, the CREDS Energy Demand Network meeting and social media. A webinar was arranged to provide additional guidance and answer questions on 26 September 2019. Forty-nine people joined the webinar, and the call documents, audio recording, presentation and Q&A transcript were made available on the website for the reference of all applicants.

Following the webinar, interested potential applicants were provided with support through on-line mentoring circles facilitated by members of the CREDS Executive. We offered 66 people two to three online mentoring sessions in groups of up to 10, involving seven members of the Executive as mentors. Applicants were also invited to email the CREDS Director and Research Knowledge Exchange manager with questions.

The deadline for full applications was 17 December 2019. Applications were required to include sections on track record, description of the proposed research, work plan and budget, and, for larger projects, pathways to impact and justification of resources (see Application form). Partner letters of support were allowed, but not required.

1.2.2 Applications

We received 75 applications, of which 68 were deemed valid, i.e. within the scope of the proposal, containing the required paperwork and not being duplicates. The valid applications were all sent to at least two independent peer reviewers. These reviewers were selected on the basis of their expertise to review the proposal. They were drawn from the existing CREDS consortium, the wider UK energy research community and some overseas experts. Reviewers did not review applications from their own institution.

Reviewers were asked to consider applications only against the criteria set out in the call documentation, namely: scientific quality, benefits to the applicant, national importance and complementarity with the CREDS Research programme (full details). Reviewers were asked to score applications on a scale of 1 to 6, using exactly the same definitions as used by EPSRC in their peer review process (where 1 = ‘this proposal is scientifically or technically flawed’ and 6 = ‘this is a very strong proposal that fully meets all assessment criteria’).

The CREDS Director and Core team ranked the applications, based solely on the review scores received. Following discussions with the CREDS Executive, it was decided to take forward the 19 proposals with an average reviewer score of 4.5 and over. The two small applications that met this criterion were funded. The remaining 17 larger projects were shortlisted and sent to the moderating panel for consideration.

In order to shorten and simplify the assessment process, review comments went directly to the moderation panel rather than allowing for applicant responses. The moderation panel was comprised solely of members of the CREDS Advisory Board, none of whom had a conflict of interest. The CREDS Director and Research Knowledge Exchange Manager acted as the panel secretariat. Three members of UKRI, 2 from ESRC and 1 from EPSRC attended as observers.

The moderation panel met on 2 March 2020. It considered the 17 shortlisted large projects. These were ranked in order and the top six were identified as fundable within the allocated budget. The overall success rate was 12%, with a small grant success rate of 14% (2 of 14) and large grant success rate of 11% (6 of 54).

Figure 3: CREDS early career researcher (ECR) flexible fund call process.

1.2.3 Immediate follow up from the process

Successful and unsuccessful applicants were advised immediately after the panel. On the advice of the panel, unsuccessful but short-listed projects were offered written feedback.

The process was then reviewed by the CREDS Executive and CREDS Advisory Board to identify any improvements that might be made. As a direct result of this review, the Research Knowledge Exchange Manager has offered feedback to unsuccessful projects that were not shortlisted but were within scope, based on the reviewer’s comments, in the form of a half hour mentoring call. This work will be completed by early July 2020.

Descriptions of the successful projects will be published when financial checks and contracts are agreed. Successful candidates were asked to provide additional demographic data so that we could compare them to the whole group of respondents to our survey.

1.2.4 Evaluation of the call

After the decision-making panel, based on a request from the CREDS Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) group, a survey was developed aimed at evaluating the perceived usefulness of the overall scheme, the support offered as part of the call and the diversity of the applicants. It was sent to all applicants and to anyone who had contacted CREDS in relation to the call. It was sent out on the 27th of February 2020 to 110 individuals and closed on 13 March 2020. This report presents the results and analysis of that survey. It will be made available to UKRI and an edited version will be published on the CREDS website. It will also be shared with other research consortia managing funding calls, such as the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) and the Centre for Climate and Social Transformations (CAST). Sixty valid responses were received, a response rate of 55%.

2. Results

2.1 Participant demographic

Respondents to the survey were asked about their gender, ethnic origins and any disabilities. They were also asked if they had caring responsibilities and whether they had permanent academic posts.

Thirty two of the 60 survey respondents were male, 22 were female and the rest did not reveal their gender. Twenty-one indicated a caring responsibility, 34 had none, with the remaining five not responding. Regarding disability and / or long-term (mental or physical) health condition, 51 indicated none, two indicated a condition, seven chose ‘other / prefer not to say’ or did not answer.

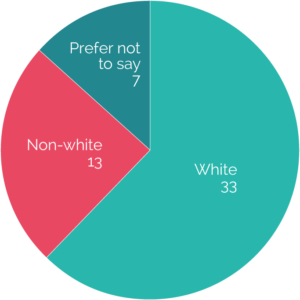

Regarding ethnic origin, 7 participants gave answers that could not be interpreted unambiguously and so are not considered in the section below (i.e. a reduced N = 53). Seven participants preferred not to reveal their ethnicity. Thirteen participants were from a non-white ethnic origin, with case numbers too small to allow further breakdown without compromising anonymity, and 33 were white.

Figure 4: Ethnic breakdown of participants.

Of the respondents, 38 did not hold a permanent academic post and 18 did. Four respondents did not answer. Hence, the large majority of almost two thirds of the applicants did not hold a permanent academic post.

2.2 Evaluation of grant

Respondents were asked about the grant – whether they applied (and if so what size of grant they applied for), what they thought of the eligibility criterion and how useful they thought the call was overall. They were also asked about the support offered during the application process – the webinar, mentoring circles and ability to ask questions of the CREDS Director and Research Knowledge Exchange Manager.

2.2.1 Breakdown of large and small applications

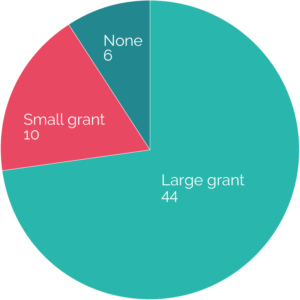

Applicants to the grant could apply for a large grant of up to £200,000 or a small grant, with slightly simpler criteria, for up to £20,000. Of the 60 survey respondents, the majority had applied for a large grant (N = 44). Our sample has 17% who applied for a small grant, compared with 21% of the group who actually applied, so can be considered fairly representative in this respect.

Figure 5: Breakdown of small and large grant applications.

2.2.2 Eligibility criterion

Respondents were asked what they thought of the eligibility criterion by which ECRs were defined for this call, i.e. that they had not led an energy demand grant in the UK in excess of £100K. Of the 60 respondents to this question, 58 thought it was a good criterion. The other two commented on the criterion (see Appendix 2 for full comments). One comment could not be understood. The other felt that the £100K criterion made it difficult to compete with very experienced people, often in permanent positions, who had not won funding but would otherwise not normally be thought of as ECRs. They suggested and additional criterion, for example, that candidates should not have held a permanent lectureship for more than 3 years, to screen out these much more experienced people.

2.2.3 Usefulness of funding call for early career researchers

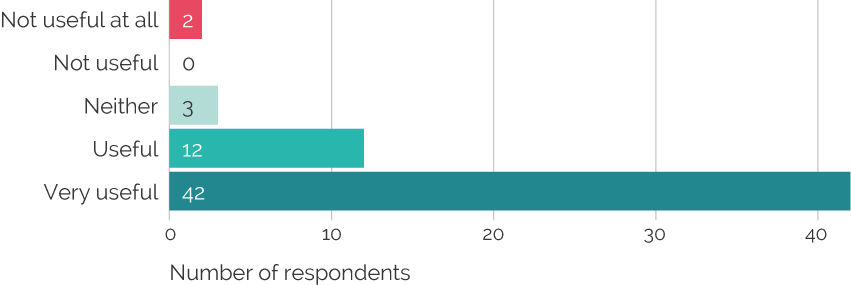

When asked how they would judge a call of this type for researchers in their position, 91.5% (or 54 of 59 respondents) said it was ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’.

Figure 6: Perceived usefulness of the overall call.

Respondents were also asked to comment openly on the call and 25 did so. For the full comments see Appendix 2. The comments reflect that the call was broadly welcomed as being focused on energy demand research, having a new eligibility criterion that included a broader range of ECRs, providing a good opportunity and stepping stone for ECRs, being well structured and supported by CREDS, and providing a valuable learning opportunity. The negative comments focus on the competitiveness of the call in relation to the work involved, a feeling that the ‘playing field’ might still not be entirely level, making the selection criteria clearer and the need to provide feedback.

2.3 Evaluation of support during application process

Potential applicants were offered support during the application process, in the form of a webinar (49 attendees), mentoring calls (66 people were offered two to three online mentoring sessions in groups of up to 10, involving seven members of the Executive as mentors) and the ability to email the CREDS Director and Research Knowledge Exchange manager with questions.

2.3.1 Webinar

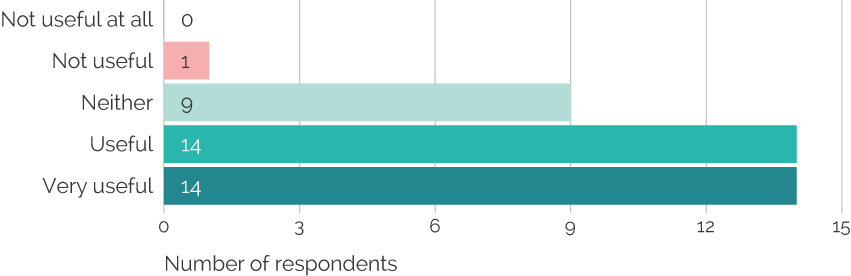

Twenty-two respondents did not answer the question on the webinar, either because they did not participate or did not remember participating. The average evaluation for the webinar was 4.08 out of 5, where 5 was considered very useful and 4 useful (SD= 0.85), i.e. it was judged as useful overall.

Figure 7: Perceived usefulness of the webinar.

Respondents were asked to comment on the usefulness of the webinar (see Appendix 2 for full comments). There was general appreciation of the webinar, the fact it had been recorded, and that the presentation and recording had been made available on the CREDS website. It was felt to provide clarity about the call, insight into CREDS and a useful opportunity to ask questions. Some people seem to have had IT issues and some would have liked more clarity about the assessment process/ criteria.

2.3.2 Mentoring circles

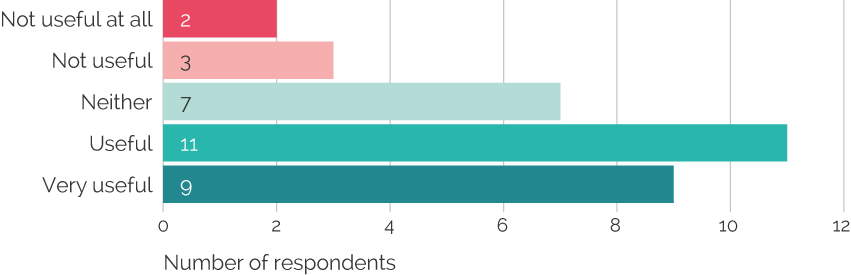

For the question on the mentoring circle, 32 participants provided an answer. The mean rating was 3.69 (SD = 1.18). Twenty participants have a rating of 4 (useful) or 5 (very useful), and 5 of not useful/ not useful at all. Respondents were not asked to make additional comments about the mentoring circles but comments collected by mentors are available (see Additional data). However, a couple of comments were made in the ‘open comments’ section of the survey (see Appendix 2). One focused on the fact that the mentor seemed too busy to deal with individual requests, though specific support is not what was offered. The other had not been allocated a mentor, which will have meant they applied after the scheme was already in progress.

Figure 8: Perceived usefulness of Mentoring circles.

It is not possible to assess the efficacy of the mentoring circles in terms of improved outcomes/ grant application quality because we did not collect the data to enable us to do so. However, it would have very difficult to do this given the variables involved – estimating the ‘level’ of a candidate prior to receiving mentoring and afterwards is fraught with difficulty.

2.3.3 Direct email questions

All but 12 survey respondents indicated having sent in questions. The mean score for how useful the answers were was 4.6 (SD = 0.74), with 5 being ‘very useful’. Questions were also judged to have been answered promptly, M = 4.17 (SD = 1.13).

2.4 Additional data

Additional data was taken from a number of sources to supplement and give context to the data presented above. In this section we compare CREDS diversity data with that of UKRI (or UK Higher Education staff data where there was no UKRI comparative data available), present data about the mentoring scheme from the perspective of the mentors, provide additional information about the reviewers and compare the survey respondent data with data on the CREDS successful candidates.

2.4.1 UKRI diversity data

It is worth comparing the demographic information from this call (see Participant demographic above) with that of UKRI applicants. We compared data on gender, ethnicity and disability. The ESRC demographic breakdown for those who applied in 2015-16 was 47% women, 53% men, 81% white; and in EPSRC was 17% women, 83% men; 79% white. Over 92% and 94% of applicants to ESRC and EPSRC grants respectively had no known disability. Caring responsibilities and academic status were not reported. The table below shows how these figures compare with those from CREDS. It should be noted that the CREDS numbers are small (n=54 responses to the survey by those who subsequently applied for funding).

Table 1: Comparison of CREDS ECR Flexible fund call applicants with ESRC and EPSRC applicants

| CREDS | ESRC | EPSRC | UK Higher Education | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 56% | 53% | 83% | |

| Female | 33% | 47% | 17% | |

| Undisclosed | 11% | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 55% | 81% | 79% | 80% |

| Other | 27% | 14% | 14% | |

| Undisclosed | 18% | 5% | 7% | |

| Disability | ||||

| No disability | 83% | 92% | 94% | 92% |

| Disability | 4% | 5.3% | ||

| Undisclosed | 13% | 2.7% | ||

The CREDS figures in this table are a little hard to assess because a significant percentage of people did not disclose their status in each category. However, the CREDS ECR Flexible Fund call performed slightly better than is normally the case for ESCR calls and significantly better than EPSRC, who would normally be the main funder of energy demand work and so our natural comparator. CREDS gender figures are similar to ESRC, and fairly well balanced, with a much higher proportion of women compared to EPSRC.

UK Higher Education staff statistics offer the most useful comparator we could find to assess our performance. In terms of ethnicity, 55% of CREDS applicants were white, which compares with approximately 80% of academic and non-academic staff in UK Higher Education who are white. Eighty three percent of CREDS applicants said they had no disability compared with UK Higher Education staff, whose figures show that 92% had no known disability, 5.3% did, and 2.7% status unknown. This means the CREDS funding call also resulted in somewhat greater diversity in ethnicity and disability, though this is only based on the survey respondents.

2.4.2 Mentors

The mentoring circles were a novel initiative suggested by the CREDS Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) group. The concept and process involved is described in see Appendix 3. Members of the CREDS Executive were asked to volunteer to be mentors. Sixty-six ECRs were offered coaching with 7 mentors (6 men, 1 woman), all CREDS co-directors.

The Research Knowledge Exchange Manager asked the mentors for their feedback on the process and the following main issues came up:

- The scheme was generally well received and served to supplement the webinar. It was useful to clarify questions around:

- The call and to highlight the importance of the guidelines (sticking to page limits, clarifying aims, complementarity with CREDS)

- Whether projects were in scope – here conversations about energy demand were helpful

- Technical issues – what was/ was not covered by the call; engaging with their own support structures early; engaging with CREDS and external stakeholders; accounting for the time of co-investigators, panels, overseas academics, people not from academia, etc.

- There were requests for individual mentoring sessions, and some of the mentors tried to cater for this, either by setting up individual calls with people or by commenting on proposals that were sent to them. The main issue here was that it could be difficult to talk about individual projects in a group session, either because of lack of time or because mentees were worried about sharing ideas with others against whom they were in competition.

- There were quite a few mentees who did not attend the mentoring calls they had been offered. There were several reasons for this. Some just did not respond, others had conflicts and some had caring responsibilities. Where they did not take up the first mentoring call, they were invited to subsequent calls so they were given another opportunity to receive support.

- People from some institutions said they were not allowed to submit bids for the small fund as their institutions would only allow them to make larger bids. They were requested to write to us to explain why but have not done so. The problem seems to lie in the 80% FEC rule but would require further investigation.

2.4.3 Reviewers

This process required a significant investment of resources beyond CREDS, most notably in relation to the reviewers who reviewed proposals and sat on the selection panel.

We asked 85 people to review (16 women; 69 men; 19%:81%). Twelve declined (1 woman; 11 men; 8%:92%). Seventy-three accepted (15 women; 58 men; 21%:79%) and each reviewed approximately two proposals. These ratios are a bit worse than involvement in CREDS (which is nearer 30:70). We relied quite heavily on CREDS investigators and senior researchers, so we have looked at the slight mismatch. The reasons for the difference are as follows:

- Seniority – a higher proportion of CREDS people who were applicants but might otherwise have been reviewers were women.

- Discipline – CREDS women are based more strongly in social sciences and the bids were mainly in physical sciences, so more ‘unused CREDS people’ were social scientists.

- Reviewers external to CREDS were largely drawn from a list provided by EPSRC, which was overwhelmingly male.

The selection panel comprised members of the advisory board: 4 men, 5 women; with 3 members of UKRI attending as observers (2 women, 1 man) and the Director and Research Knowledge Exchange Manager from CREDS acting as the secretariat (1 man, 1 woman).

2.4.4 Data on successful candidates

Eight applicants were funded. As part of this evaluation, they were contacted with additional questions so that they could be compared with the survey respondents. They were asked their gender, ethnicity, whether they had caring responsibilities, whether they held a permanent post, and how long it was since their PhD. We also compared them whole group of applicants where information was available, such as comparisons of scores, information about their institutions or prior involvement in CREDS.

The group of successful candidates breaks down as follows. There are 8 researchers leading 2 small bids and 6 large, totalling £912,810. There are 3 men and 5 women, 2 non-white and 6 white people. Three have caring responsibilities. Three have a permanent post. The shortest time since completion of their PhDs was 1 year, 5 months and the longest was 6 years, 10 months (which included two maternity leave periods).

The table below compares the successful applicants with the survey respondents. It should be noted that the number of successful applicants (n=8 for the successful applicants and n=60 for the survey) makes it difficult to compare the data.

Table 2: Comparison of successful applicants with survey respondents (figures in parentheses indicate % undisclosed).

| Percentage | Successful applicants | Survey respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 63% | 37% (10%) |

| White | 75% | 62% (13%) |

| Caring responsibility | 38% | 35% (8%) |

| Permanent post | 38% | 30% (4%) |

Three successful proposals were led by researchers from UCL. The others were led by researchers from Birmingham, Coventry, Edinburgh, Lancaster and Plymouth. This compares with the number of applications received arranged by institution, as seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Institutions represented in call (dark shaded institutions are in the Russell Group; an asterisk denotes the involvement of the institution in CREDS, though it may be a different part of that institution)

| Institution | Applications | Shortlist | Funded |

|---|---|---|---|

| * UCL | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| * Sussex | 3 | ||

| * Surrey | 3 | 2 | |

| Salford | 1 | ||

| Royal Holloway | 1 | ||

| * Reading | 2 | 1 | |

| Plymouth | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| * Oxford | 1 | 1 | |

| Nottingham | 2 | ||

| Newcastle | 3 | ||

| * Manchester | 1 | ||

| London School of Economics | 1 | ||

| London South Bank | 2 | ||

| Loughborough | 2 | ||

| * Leeds | 9 | 2 | |

| * Lancaster | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Keele | 2 | ||

| Imperial College London | 3 | ||

| Heriott Watt | 1 | 1 | |

| Exeter | 4 | ||

| * Edinburgh | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Durham | 1 | ||

| Cranfield | 3 | 1 | |

| Coventry | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiff | 1 | ||

| Bristol | 3 | 1 | |

| Bolton | 1 | ||

| Birmingham | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Bath | 2 | ||

| Aston | 1 | ||

| Anglia Ruskin | 2 | ||

| Total | 75 | 19 | 8 |

As can be seen the table, ECRs from a wide range of institutions across the UK were involved in the call, suggesting good coverage and broad participation. ECRs from 31 institutions applied, 13 of which were from the Russell Group (42%) and 9 of which were previously involved in CREDS (29%). At the level of individuals, the number of call applicants employed by CREDS at the time of submission was 12, with one of them winning funding.

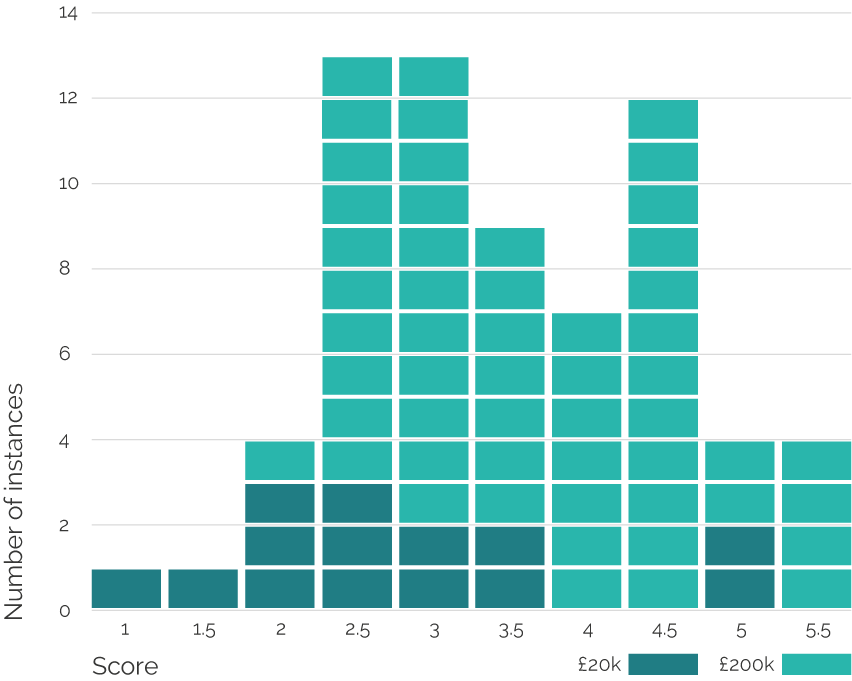

Figure 6 shows the spread of scores from the review process. Twenty-seven of the applications (40%) received a mean score of 4 or higher, which means they were considered to have submitted “a good proposal that meets all assessment criteria but with minor weaknesses”, in other words, an essentially fundable proposal. Sixty percent of candidates scored 3.5 or less and 40% scored 4 or over. Except for the two that were funded, small applications tended to score lower. Of those applicants who achieved a mean score of 4 or over (n=27), 20 (74%) were from institutions involved in CREDS and 20 (a different subgroup but with significant overlap) were from institutions in the Russell Group.

Figure 9: Mean scores of applications (Dark shading denotes small grants)

3. Learning

3.1 The grant

Overall, the CREDS ECR Flexible Fund call was a success. Eight high quality proposals were funded into research complimentary to CREDS. The ECRs involved will be offered project management support and other capacity building opportunities by CREDS. Apart from this, their careers will most likely benefit because they will have improved their CVs by winning money, gained experience as Principle Investigators (PIs) and enhanced their networks through active involvement with CREDS.

The grant was enthusiastically received as can be seen in the open comments about the usefulness of the call (see the full Call documents) and, anecdotally, we received many emails and comments from ECRs grateful for the opportunity. The high number of applicants indicates an appetite for further calls of this type and the fact that we received a high percentage of fundable applications shows that funding ECRs is not especially risky in terms of public investment in research. Although ECR funding does exist it tends to be focused on individual fellowship-type funding rather than grant funding and so this more project-type funding is a welcome addition to the funding landscape. In particular, allowing those with non-permanent posts to apply was helpful as both ESPRC’s standard grant programme and New Investigator Award require permanent contracts.

The focus on demand and chance to be involved in a call in an interdisciplinarity environment was welcomed. The call was seen as well-structured and well supported by CREDS, providing a good opportunity and stepping stone for ECRs, and affording a valuable learning opportunity. There was some evidence that small grants are difficult for some institutions to process because of the 80% FEC rule but more evidence would need to be collected to understand the reasons better.

There is a general move towards removing year-based eligibility criteria from grants, and CREDS followed this trend. The qualification criterion (that the call was open only to applicants who have not previously held an energy research grant exceeding £100k in size) was well received (97% thought it was a good criterion) although, by definition, our evaluation will not have heard from those who did not meet this criterion and who, therefore, might not have been in favour of it. It may also be worth thinking about additional criteria that would screen out more experienced people in the ECR category, such as excluding people who had been in a permanent post for more than 3 years, excluding breaks for maternity cover or other caring roles. Certainly, however, different criteria open up the field for different people to apply and so encourage diversity.

It is not uncommon for a programme to administer relatively small amounts of funding. Nevertheless, CREDS doing so meant applications had an energy demand focus and successful projects will immediately be integrated into the energy demand research context and community. However, there were also costs to running this call. The scheme placed a significant time and resource burden on the programme and meant that programme staff had to deliver against a new set of deliverables than is normally the case in an academic programme. Apart from the implications for CREDS, the call also involved 85 reviewers and 14 people on the selection panel, all of whom invested a significant amount of time and expertise in the process. The CREDS Core team has also spent a very considerable amount of time administering this call. Resources need to be made available for programmes to be able to support such work.

There should also be consideration of the implied opportunity cost involved in this time allocation as that time would normally have been spent on programme outputs. A balance between the costs and advantages of programmes managing their own funding needs to be pondered, perhaps through a comparative evaluation.

Finally, CREDS is not a Research Council and so does not have the requisite systems to run a funding call. We made a few errors as a result, which, although they did not influence the ultimate outcome, were time-consuming to resolve. Perhaps the biggest error was not allowing the applicants to respond to reviewers’ comments, which was done for timing reasons. In retrospect we denied our applicants a key learning process in submitting a successful proposal. Learning to respond to reviewers’ comments is a valuable art and key for ECRs to be successful applicants. Also, because there was no opportunity for applicants to correct reviewers’ mistakes and it made it more difficult to send reviewers’ comments back to applicants afterwards.

3.2 The process

Apart from its focus on ECRs and the way they were defined, the scheme itself was novel in several respects relating to its process. One area of novelty was the support offered during the application process, which comprised a webinar, mentoring circles, the ability to ask questions and the provision of training for CREDS ECRs (the resources for which were put on our website). There were a few technical issues that could be improved but otherwise this support was appreciated and worth doing if only for that reason. The high uptake of this support would suggest it be considered for other funding programmes too.

However, there was also a feeling that this support was too general. Despite the concentrated ECR focus, additional procedural support, and attention to equality, diversity and inclusion, the process was criticised for not offering individualised support during the application and feedback after the reviews/ assessment. Targeted support specific to the individual needs of applicants was not possible for this call because the resources required would have been too great. Although this was not possible for this call, certain adjustments might make it more manageable in future.

It is worth considering how to improve the capacity of all researchers (not just ECRs) in relation to funding. Bespoke training and mentoring schemes could be run by funders, doctoral training centres and/or programmes like CREDS if they were properly resourced to do this work. This would improve the quality of applications and so benefit researchers, funders, the public (who ultimately pays for research), as well as those stakeholders who benefit from its impacts. It would also give ECRs a better chance of competing against more established researchers in open calls.

Such support would improve the overall quality of proposals, which the CREDS experience would suggest is needed. Partly due to the focus on process during the support offered to candidates, few were disqualified. Nevertheless, 7 applications (nearly 10% of those received) were ineligible or out of scope (i.e. did not include the required paperwork or were not focused on demand) even though we erred on the side of generosity for small errors in paperwork which might have disqualified applicants in other circumstances. Of those proposals that were eligible, a healthy 40% scored 4 or higher but 28% received a score of 3 or lower suggesting they did not meet one of the criteria or were scientifically flawed.

In speaking to unsuccessful candidates in one-to-one mentoring calls now that the call is over, the toll of continuous rejection becomes clear, with many feeling demoralised, angry or confused. Given the public and personal investment required to get people to the level necessary to submit a proposal for grant money, this human cost seems unfortunate. A system that repeatedly rejects the majority of candidates seems wasteful, and is certainly not good for peoples’ mental health. ECRs, and researchers in general, are subject to a great number of pressures, such as insecure and short-term contracts, the expectation that they will constantly move institutions to follow the work, heavy workloads with poor pay, and often poor management and working conditions. The difficulty of securing funding and the lack of support involved – most PhD programmes do not train people on how to secure funding, most researchers are not mentored in this area, most institutions are very hierarchical and do not value or support the funding aspirations of those lower down the ladder – means that many eventually leave academia, which is an obviously undesirable outcome.

Apart from the training and mentoring suggested above, one important way of enhancing capacity and improving future bids is by offering feedback. Initially CREDS decided not to do this because, whilst some research councils routinely share the reviewer forms with the applicant, others do not give any sort of feedback to non-shortlisted candidates, the resources required are potentially substantial and there is a risk of getting into a debate with applicants. This decision attracted more criticism from applicants than any other feature of the call. They argued that it was impossible to learn without feedback and that feedback was particularly important for ECRs. On reflection, we agreed and we have taken immediate remedial action.

On the advice of the selection panel, we started by giving written feedback to the successful and shortlisted candidates based on comments from the selection panel. After consultation with our advisory board we decided to offer feedback to unsuccessful candidates too, based on comments from the reviewers, in the form of a half hour mentoring call with the Research Knowledge Exchange Manager. This is not normal practice in academia but we believe will further enhance the positive impact of this call. Apart from the fact that for administrative reasons it was not possible to share reviewer forms with applicants, it also seemed more helpful to have a conversation to give applicants the chance to ask for clarifications and seek advice. I have been personally struck, during these individualised mentoring sessions with unsuccessful candidates, by how grateful they have been and how helpful they have found it. This suggests that many are not finding this sort of support elsewhere.

In the end, therefore, offering feedback has become a significant undertaking, mainly because permission was not originally sought from reviewers to share their feedback. As outlined at the end of the previous section, this is our main learning from the process. It would also be worth being clearer with reviewers about what is expected of them. Doing reviews is often viewed as a burden, an unpaid and unrecognised part of being in the research community, and this can be reflected in the quality of the reviews. Reminding reviewers of the call criteria (so they are less likely to make mistakes) but also of the value of their insights and the impact of their reviews may help improve the feedback they offer when they are under pressure.

Apart from learning based our own reflections on the process, we have also engaged in a comprehensive evaluation of the scheme, encompassing all those involved in the process, the result of which is this report. Invitations to comment on funding schemes are not common practice in our community, which means opportunities to learn and improve are limited. This evaluation focused on the process but also the demographic makeup of those involved, comparing that to both our own successful candidates and to EPSRC/ESRC application figures. We shall discuss these next.

3.3 Demographic breakdown

In terms of gender balance, inclusion of those with disabilities and ethnic diversity, the CREDS ECR Flexible Fund call performed slightly better than is normally the case for ESCR calls and significantly better than EPSRC, our natural comparator. Hopefully this is at least in part due to our paying attention to this aspect of the call. However, the strongest explanation for this is probably that the call was focused on ECRs, who are a more diverse group than those higher up the academic career structure, particularly in technical and engineering-based research areas. This conclusion is strengthened by looking at the demographic breakdown of reviewers, who were 79% men (though, given the fact that UKRI mostly funds men – see UKRI diversity data – cause and effect are intertwined). CREDS also performed well if compared with UK higher education in general, displaying greater diversity in ethnicity and inclusion of those with disabilities.

CREDS has led the way in the energy demand community in developing an equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) strategy and we have an active EDI group. However, it is clearly the case that more needs to be done to enhance EDI in our community. It can be difficult to know what individual programmes can do to combat such persistent and strong inequalities but the following would help:

- Improved monitoring at all levels is needed and should be a requirement of funding. The demographic breakdown of people at different levels of our community would be helpful to know. It is also important to monitor who is making decisions about funding and other opportunities – reviewers and panels need to be monitored and reported on.

- Diversity needs to be protected. How this is done is a subject beyond the scope of this report but mechanisms include training, providing opportunities for particular groups, ensuring that those from minority groups are protected from discrimination, creating a diversity-friendly research environment, and making diversity a requirement of receiving funding.

- Academia needs to pay more attention to these issues, to publish about them and to make policy recommendations. This report is an attempt to support that process.

4. Recommendations for UKRI

4.1 Diversity

It may be possible to achieve greater diversity by:

- Requiring that programmes have EDI strategies and report against them as part of their funding.

- Using a variety of qualification criteria for grants.

- Focusing on and recording the demographic details of reviewers and panels.

- Monitoring the gender, ethnic diversity and disability of funding calls, programmes, etc.

- Attending to the language of calls to eradicate gendered or otherwise biased language.

- Paying attention to interdisciplinarity and making sure there is a good mix of social and technical projects.

4.2 Quality

Higher quality proposals for both ECRs and more experienced researchers are more likely if:

- Bespoke training is developed (to be run by funders, doctoral training centres, programmes).

- General process and specific individualised support is provided (for example, mentoring others during the grant writing process could be a condition of receiving a grant).

- Specific feedback is routinely offered to applicants, if possible with the relevant information to help them put this into context (by passing on reviewer forms, publishing success rates).

- Evaluations of the funding processes are undertaken and whether they are producing the desired results, not just in terms of research outcomes but also in terms of retaining people in academia, enhancing the diversity of our community and producing research relevant to our society.

4.3 Decentralisation

Allocating some funding to programmes rather than managing it all centrally has both advantages and disadvantages and these need to be considered:

- Those funded are immediately part of an integrated research community but ECRs may need additional support.

- Programmes may have an opportunity to innovate with support mechanisms and eligibility criteria not available to research councils though this needs careful thought.

- Evaluations, learning and guidelines need to be shared to reduce the risk that programmes make mistakes given that funding is not the normal focus of their work.

- A comparative evaluation of programme-based funding would reveal both best practice and learning, and could assess the cost-benefit of time spent administering funding vs. research outputs.

4.4 Support for ECRs

Efforts need to be made to enhance diversity higher up the energy demand career structure. Demographically ECRs are more diverse than more senior researchers and so keeping ECRs within the academic community is key to maintaining a healthy, vibrant research agenda. There are many ways of doing this that were not covered in this survey, several of which are being done by CREDS and will no doubt be reported elsewhere in time, such as capacity-building programmes, involving ECRs in more responsible tasks, mentoring, and so on. Ways of keeping ECRs within academia would include the following:

- More diverse criteria by which to define ECRs would be helpful, such as the criterion used by CREDS.

- Supporting researchers on non-permanent posts would open up a lot of opportunities for ECRs. To work, this needs a coordinated approach from funders and universities.

- Additional funding for ECRs would be highly appreciated, both grant and fellowship-based. In the case of CREDS our call led to a high percentage of high quality proposals so the additional risk of funding ECRs seems minimal compared with the advantages.

- To make the most of it, ECRs could do with extra support in personal, professional and proposal development. Although general help is useful, targeted support is even more valuable and is greatly appreciated.

- A more community-focused (as opposed to only competitive) system, where people who get funding help others towards success, may help to deal with the resource constraints in offering such support.

Developing a framework to help reviewers to share constructive, thoughtful feedback on proposals would help make the most of this time-consuming process.

Publication details

Higginson, S. and Huebner, G. 2020. Evaluation Report: CREDS early career researcher flexible fund call. Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions, Oxford. ISBN 978-1-913299-03-3

Banner photo credit: Alireza Attari on Unsplash