Alice Garvey and Robin Styles

It seems that everyone is talking about plant-based diets, going vegan or at least ‘flexitarian’. So why do we need another piece of research on why meat is bad for the planet? This is certainly a question I’ve asked myself whilst working on this project – the question of how to have any impact when the impacts seem so well established.

Let us first consider the impact of our current situation; the UK’s consumption of food is responsible for 11% of our Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. But when you consider the global impact of what we eat, our emissions are 52% greater. This is not the only worrying aspect. Between February and August 2021, approximately 10% of the UK population were living in food insecurity (where nutritious food is not affordable or accessible). Coupled with this, in 2017 65% of UK adults were considered to have an overweight or obese Body Mass Index (BMI). Brexit’s impact on food supply chain stability and the pandemic’s influence on food affordability only add heat to the argument for food system change in the UK.

So just as there is a clear need for change, so there is a clear need for research.

However, apart from a few key studies telling us what to eat for planetary health, there was little in the literature we read that suggested the scale of mitigation we could achieve through ambitious dietary change, let alone accounting for the UK’s population specifically. Given the critical need for action in every sector to achieve net-zero by 2050, we wanted to find out the potential contribution of demand-side food system change to achieving the UK’s climate ambitions. By demand-side change, we mean the changes that can be taken by consumers at the end of the food supply chain – focusing on the fork rather than the farm.

‘Net-zero nutrition’ and demand-side change options

We developed scenarios of changing UK diets from 2017 to 2050, and the resulting changes in the UK’s food carbon footprint (see Figure 1). We looked at three main areas of demand-side change: shifting diets to more plant-based consumption, moderating calorific intake to the level of the Government Dietary Recommendations, and reducing food waste.

The research was initially part of the CREDS Positive low energy futures project, which explores how energy demand reduction could achieve net-zero in the UK. However, it soon became clear that in exploring seemingly simple questions like ‘how many vegans are there in the UK?’ and ‘how many could there be?’, there was scope to expand the analysis into a project of its own.

We published the findings of our scenario analysis in Journal of Cleaner ProductionOpens in a new tab , finding that the mitigation options we explored could as much as halve the UK’s food emissions by 2050. Though our initial audience was predominantly an academic one, the work has proven fairly malleable in who it’s reached, partly due to the number of formats it has appeared in.

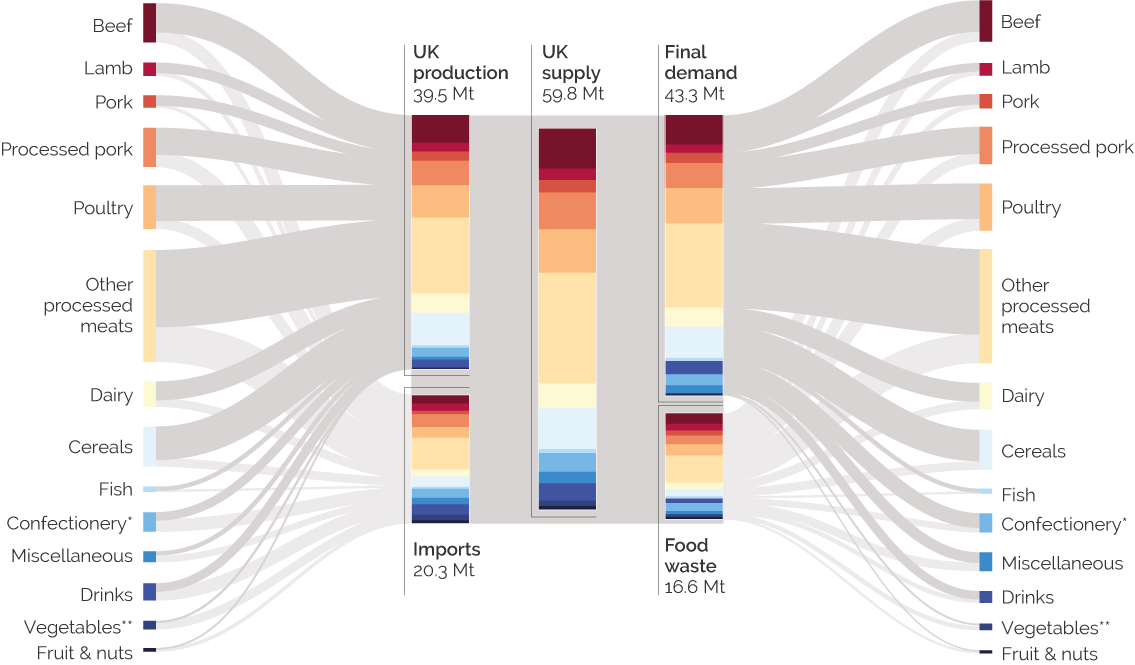

Image description

Sankey diagram shows consumption-based emissions for sectors of the food industry. Processed meats other than pork account for the largest proportion of emissions, followed by beef, poultry and processed pork. Sectors that account for the lowest emissions are fruit and nuts, fish, and vegetables.

Searching for a recipe for research impact

The need to explore, experiment, and – ultimately – implement, food policies has been underscored by the publication of the National Food Strategy and the Government Food Strategy. The discovery of the hasty deletion of a government document suggesting the potential for a meat tax in driving behaviour change also points towards the evidence-based need for sustainable food policy.

From the start we tried to make the study policy relevant, first contributing the interim analysis to the Call for Evidence on the National Food Strategy. The journal article also explored some of the main policy options to implement the scale and pace of dietary change we had proposed. Though demand-side change is driven primarily by the consumer, policy still has a role to play. We updated and expanded the policies we drew upon in the paper for a policy brief, published alongside a blog in January 2022 to coincide with ‘Veganuary’.

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| October 2019 | Response to the National Food Strategy call for evidence |

| January 2021 | Journal article: Net zero nutrition (Journal of Cleaner Production) |

| March 2021 | WRAP / CREDS resource efficiency report |

| July 2021 | BBC Radio 5Live Breakfast programme BBC News Channel |

| August 2021 | BBC 5Live website article contribution |

| September 2021 | University of Leeds Global and Envrinment Institute best graphic award |

| December 2021 | BBCC Radio Leeds |

| January 2022 | CREDS policy brief CREDS policy blog |

The underlying model from the original analysis was also used for a collaborative report with WRAP, and Defra also provided feedback on the paper, meaning the analysis had a few different points of policy contact.

The work was also promoted indirectly through media interest in several forms. In July 2021 I spoke about the carbon footprint of a full English breakfast on BBC 5 Live, research which was also written up as an article for The Conversation. Then in December 2021 I was asked to talk about the ‘foodprint’ of a Christmas dinner on BBC Leeds. Though not directly targeted at discussion of what a net-zero food system would look like, or even ‘demand-side’ change, these engagements presented a clear opportunity to get to the heart of the research – namely, the fact that meat and dairy contribute about a third of all global GHG emissions associated with food.

Although a figure included in the paper won an award at the University of Leeds (see Figure 1) for communicating the issue of food carbon footprints, the media engagement opportunities associated with the project presented challenges in clearly conveying how diets can be more sustainable. Not least when the previous speaker on BBC 5 Live was a local butcher. Similarly much debate circulated around food miles despite the fact that only about 1% of the emissions impact of a product like beef comes from the transport stage.

Just as public policy on dietary change may have stalled due to a fear of controversy, so is it hard to state the facts of sustainable diets without incurring some kind of opposition. It is a question of how food suggests an individual’s values, and in suggesting there should be change you are fundamentally challenging worldviews. Food plays an important cultural and social role, and this presents limits to some kinds of change – for instance, where diets are followed for religious reasons. It is also hard to talk about demand-side change specifically, without implying that it is solely the responsibility of individuals. This is why it is so important to emphasise the policy steps that can be taken. These are issues no doubt true of climate research in general.

In essence, the research was repackaged in several different formats, sometimes by design, sometimes by chance, all the while emphasising the key issues at the heart of the food system’s climate impact. Clearly there was no ultimate ‘recipe’ to follow for sharing the research, but we tried to be adaptive and policy-relevant even as the policy context tended to change.

Next steps on the sustainable food pathway

Although this study is largely complete, there remain several directions through which it could be expanded.

The original analysis was highly detailed in its representation of diets and calorific intake, limiting the opportunities to explore areas like the economic impacts of the dietary scenarios. The UK food and drink sector is a high value flagship industry, and therefore a key research need is in exploring how dietary change could impact this. This also raises complex policy questions around carbon leakage and the possible effect of a meat tax. Another branch of further research could concern the variability in the carbon footprint of plant-based diets. Whilst constructing the profile of a ‘typical’ vegetarian diet and surveying the literature, it became clear that not all plant-based diets are equal. Given the original analysis was scenario based, there is also scope to explore how demographic change could affect the likelihood of the scenarios being realised – i.e. will the culture for plant-based diets in younger age groups drive population-wide change towards 2050?

Ongoing collaborative policy work with GO-Science provides future opportunities for impact from the food model and its findings. The work has raised more questions than answers (an unhappy fact of scenario analysis), but hopefully with follow-up research, they are questions we’ll be in a better position to answer.

Project team

Source

Garvey, A., Norman, J.B., Owen, A. and Barrett, J. 2021. Towards net zero nutrition: the contribution of demand-side change to mitigating UK food emissions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 290: 125672. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125672Opens in a new tab

Publication details

Garvey, A. and Styles, R. 2022. Future food footprints: Sowing the seeds for change? Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions. Oxford, UK. CREDS case study.

Banner photo credit: Alireza Attari on Unsplash