Mike Colechin and Clare Quigley

This workshop was a joint event organised by CREDS and UKERC.

The organisers would like to thank the workshop participants for their time and expertise without which the recommendations wouldn’t have been identified.

Recommendations

- The data sharing experience of others is important – we need to secure better access to data for sharing, and make the methods, tools and guidance on how to do this more easily available. Energy consortia have a role in setting expectations and developing/pointing to resources.

- Providing metadata and good quality data indicators takes time. Managing data across multiple institutes, ethics teams and collaboration agreements can be complex. The different disciplinary domains common to energy consortia may have different standards that need to be All of these require expertise, attention and resourcing.

- Creating better data sets requires them to be more highly Institutions need to take the value of data more seriously, funding activities effectively, rewarding individuals for taking an active role, and recognising the importance of workload management. Energy consortia should help to set this framework as part of their culture.

- Data Management Plans are an essential starting point and should be in place at the beginning of However, to make most effective use of them, theyshould also be flexible, with appropriate mechanisms in place to reflect and learn as change occur.

For large energy research centres in particular, proposals need to budget for a data manager, recognising that this is an important role requiring appropriate remuneration to secure quality personnel.

- Not all data are The skills of the data manager should provide guidance and support to help discriminate between the value of different data sets and prioritise management effort accordingly.

- Skills and knowledge in the area of data management vary widely across the energy community, partly because of the involvement of so many different Training is required to improve researcher awareness of the value of data sharing and to improve their data management skills. Energy consortia can provide/host this training and have a role to play here, emphasising the domain aspects of data management.

- A peer network for data managers and data stewards would be useful to enable sharing of best practice and identify areas to work on together to embed FAIR data and Open Research practices within researcher’s activities. Building on existing Energy Consortia collaboration activities, such as the Cross-Consortium Engagement Meeting (CCEM), would get this process started.

- The energy community is a large producer and user of models in a wide variety of areas and common standards for what to archive to enable FAIR data and reproducibility have not yet been agreed. Such protocols would be helpful to discuss. The energy research specific issues for sharing the outputs of energy models should continue to be highlighted.

1. Introduction

Sharing energy research data is good practice for responsible research (though there are particular data sharing challenges in this sector) and many funders now require it as a condition to receive grant funding. However, it is still often seen as a burden and many projects fail to fully deliver on FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) data sharing commitments. This workshop brought together key stakeholders in the whole research lifecycle to develop recommendations for improving the level and quality of data sharing within the energy community (from pre-workshop briefing note by Catherine Jones and Sarah Higginson).

This report summarises the outputs of an online workshop, jointly organised by CREDS and UKERC, held on 19 October 2023. The organising committee consisted of Sarah Higginson (CREDS), Catherine Jones (UKERC), Marina Topouzi (Oxford), Michael Fell (UCL) and Gesche Huebner (UCL), any of whom can be contacted for more information on the contents of this report.

The workshop brought together a range of stakeholders from the energy research lifecycle including consortium leads, data managers, researchers, publishers and funders.

Outputs include:

- A summary of key lessons (captured in this report)

- A set of recommendations (to be shared with participants)

- A blog (to be shared with the wider research community via the CREDS and UKERC websites and newsletters).

This workshop explored lessons relating to data sharing in the energy research domain from the perspective of different stakeholders and used these lessons to develop recommendations.

The workshop included three short talks/presentations. The first was from UKRI to set the context, and then from both CREDS and UKERC, outlining their experience of research data sharing and management.

In breakout groups, participants were asked to:

- Reflect on the experiences of CREDS & UKERC and capture lessons learned from broader experience

- Consider what is needed to deliver effective data sharing

- Identify the main barriers to sharing energy research data

- Explore potential solutions and the means to take them forward

- Develop and prioritise recommendations.

A visual tool (Mural) was used to capture responses from participants during the group discussions. A FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) data sharing framing was used for this process. This created a complex mapping of responses, which were subsequently analysed and arranged under four new headings: ‘Resources’, ‘People’, ‘Methods and ‘Technologies’. These are presented in the Stakeholder Responses section of this report. In each case, the workshop sought to capture lessons learned, key barriers to data sharing, and views on the pre-requisites for effective data sharing.

The Appendices to this report provide a detailed account of the workshop and participant responses.

2. UKRI, CREDS & UKERC experience – talks / presentations

2.1 Rachel Bruce – UKRI context setting

As Head of Open Research at UKRI and lead for the Pan UK research policy for open access, Rachel set the context for developing research data strategy and policy within UKRI. She emphasised her interest in hearing about different approaches to research data management and in identifying specific challenges and opportunities. UKRI wish to invest in and support best practice with availability of research outputs as a key cross-cutting aim.

In this context, the main drivers for UKRI, when it was established in 2018, were:

- Open access to

- Research data policy and practice to enhance trust and transparency (with a common principle to be as open as possible, as closed as necessary).

UKRI is working for best practice in innovation in a UK context, but also globally with partners and funders around the world. Part of their corporate plan includes updating their research data joint principles, and then each Council has its own policy. Global collaboration is important, as is data sharing across sectors. Open research is a key aim with support from best policy and practice across all disciplines.

UKRI has invested in more cross-disciplinary research and has enhanced the focus on reproducibility. They are currently working on reforming the research assessment to incentivise data sharing. Across the Research Councils they are developing new requirements and best practice.

UKRI reviewed what happened with data sharing during the pandemic and recognised the need for cross-disciplinary policies.

OECD data recommendations were updated in 2021, and these will be considered when refreshing UKRI’s policies in the future. There is more on e.g. footprint data, usage data, AI adoption. These issues are also being considered in the development of the Research and Excellence Framework (REF) 2028.

In the future, UKRI policy will address the whole pipeline, including new data types and cross-disciplinary working. It will seek to make sharing research data as easy as possible and identify how UKRI can support that, with a particular emphasis on cost- benefit.

2.2 Sarah Higginson – CREDS’ experience

Sarah talked about the CREDS’ experience of the challenges involved in making the findings available from across nine separate themes.

She talked about the difficulties of recruiting and retaining Data Managers, an issue they addressed by setting up an internal ‘good data practice’ project and securing bespoke support from the UK Data Service.

Specific interventions from the CREDS Core Team included:

- Setting up a Research and Data Quality Project and selecting a Quality Champion from each of the nine theme areas to increase awareness, skills and communication linkages across the consortium.

- Reporting on progress at Whole Centre Meetings and in quarterly

- Producing a video series about improving the transparency, reproducibility and quality of research (TReQ).

- Encouraging every theme to produce a Data Management Plan and then collecting and cataloguing this data.

- Setting up a collaboration with UKERC on the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH).

- Setting up a workshop (reported on in this document) to coordinate shared learning with system stakeholders and to develop recommendations for future research consortia.

Specific lessons learned include:

- Many researchers are unaware of TReQ

- There are different research cultures and many different types of

- Data Management is not a priority and is often left until the end of a (This can create issues with ethics approval processes if participants are not asked for permission to share their data. There is a related issue here in that data sharing is not highlighted by ethics approval processes, which is an institutional issue).

- Data Management takes time and effort.

- There is a need for greater clarity around basic processes g. preparing the data for archiving, making sure it is supported by quality metadata, checking that data has been archived ready for sharing.

- The loops are gradually being closed – publishing, funding, consortia are increasingly focusing attention on the importance of data sharing.

2.3 Catherine Jones – UKERC experience

Catherine has been involved in data access, management and sharing for many years and has worked for three years in the energy sector, specifically as part of UKERC’s Energy Data Centre (EDC).

- UKERC has been running for 20 years and has 20 project partners.

- UKERC’s current phase (Phase 4) consists of 7 themes, 3 capabilities and 3 rounds of external projects – an £18M programme.

- UKERC’s EDC provides an expert team, a discovery portal and a compendium of UK energy research data.

- UKERC’s vision is to provide independent whole systems research for a sustainable energy future.

- UKERC expects every project it funds to create a Data Management Plan and the majority of projects have an approved plan.

- During Phase 4 they have made data publicly available, with seven datasets in the EDC, three in the UK Data Archive, and one in an institutional repository. (There are some sharing restrictions where these have used third party data).

- UKERC Phase 4 has a clear view of what research data are being produced and what is openly available.

2.4 Challenges and lessons learned

Following these three presentations a Q&A session explored the challenges and lessons learned in more detail.

- Energy research covers a wide variety of disciplines with different expectations, practices and repositories.

- Data management planning is part of good research practice and contributes to reproducability.

- Preparing data for archiving can take a significant (often un-budgeted) amount of time – this can be significantly reduced by creating an effective Data Management Plan early in a project.

- There are challenges around the data itself, not least the ethical implications of archiving data – again, early development of a Data Management Plan will help to avoid these issues.

- Data Management Plans need to be tailored to the scope of the project – large consortia need more complex processes than smaller projects, but there’s no question that they all need something.

- Publisher requirements on data access statements are starting to change researcher the amount and type of data to be stored and the duration of that storage, not least when considering modelling outputs.

- Jupyter notebooks provide a useful research tool, but they are difficult to preserve as part of a data archiving process.

- Data from UKERC Phase 4 will be publicly available and discoverable where appropriate via the EDC.

3. Stakeholder responses

To gather the views of the stakeholders who had attended the workshop, participants were divided into six groups for the first session, with a mix of stakeholder roles in each group. The main focus of the discussion was to reflect on and learn lessons from the experiences of CREDS, UKERC and the wider stakeholder community represented at the workshop. Participants were also asked to consider what is needed to deliver effective data sharing whilst identifying key barriers to this process.

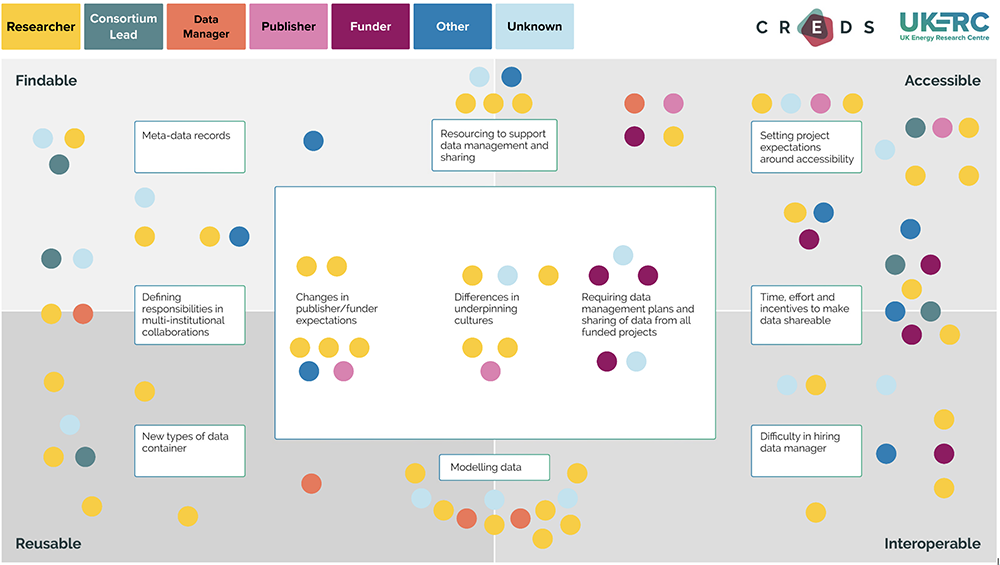

A visual tool (Mural) was used to capture responses from participants during the group discussions. These were captured using the FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) data sharing framing, and participants were asked to self-identify which role they hold (consortium lead, data manager, researcher, publisher, funder or other) when making responses. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses from each participant group within this framing.

The responses of the participants are captured in detail in Appendices 4 & 5 in the downloadable pdf.

In the following section further analysis of these responses has been undertaken using a framing based on some previous analysis by the project team which had suggested four key considerations for effective data sharing:

- Resources: The need for synchronisation between research objectives and project management.

- People: The impact of different actors in the process.

- Methods: The potential for consistent metrics or a set of principles that facilitate project comparisons and are sympathetic to both quantitative and qualitative research traditions.

- Technology: This includes both testing novel technologies and data collection technologies.

3.1 Resources

Using this framing, perhaps the most fundamental issue identified in the workshop was that of ‘resources’. The key ‘lesson’ captured in this regard was that it is easy to underestimate how much resource is involved in delivering effective data sharing, and this was reflected in a number of the barriers identified.

It was generally felt that insufficient resources are assigned to the process, a problem which is compounded by the general ‘lack of time’ in a modern university. Also, the perception of data sharing is that it is ‘time consuming, difficult and frankly not interesting’. Submitting data to an official repository can be an ‘admin-heavy process’ and if no-one is checking that data is being made available it drops down the priority list. Added to this, managing data across multiple institutes, ethics teams and collaboration agreements is difficult, and funding for the delivery of open access project outputs can be limited.

The stakeholders suggested that addressing these issues requires greater recognition in institutions and research centres of the value of data as an output, supported by funder policies for sharing data. Positive incentives would encourage applicants

to consider data sharing at the project proposal stage and ensure that appropriate agreements are established with quality, usable data as a project output, whilst recognising that not all data can be shared and there is a cost to managing and storing data. These agreements should plan and map data flows and clarify data management arrangements. There was also a recognition of the importance of effective project management in the process, assisted by appropriate communication and engagement support.

The presentations from CREDS and UKERC emphasised the importance of creating a Data Management Plan early in a project. There was a lot of agreement around the importance of these and the need to review them to ensure that they are comprehensive as a means of delivering focus on data sharing earlier in the research process. This may be helped by the creation of good, detailed guidance at institution or even at UKRI level.

However, some stakeholders did raise questions around the role of Data Management Plans, and even asked whether they were needed in all situations. There was a desire to simplify the process where possible, which was seen as especially important for projects with lower resources and/or without a data manager. It is only possible to ‘plan in detail for what is known now’ and plans need to be able to handle changes.

Concerns were raised about creating data sharing policies based on the principle that ‘it is a good idea’, and consequently having to prepare data in a way that ‘meets all possible needs’. Qualitative differences were identified between data produced as a product for others compared with data used internally for a publication. It was suggested that different levels of effort may be appropriate in each case, which resonated with questions around the ‘value’ of specific data sets.

The ability to recognise the ‘re-use value’ of datasets was seen as important in directing effort appropriately, potentially supported by an effective cost/benefit analysis. A key question identified was, ‘How long should we keep research data when don’t know what will be reused?’

3.2 People

The availability of resources is closely related to the impact of different actors in the process, and a number of the data sharing issues discussed in the workshop were related to the role of ‘people’ in the process.

Individuals experience ‘many disincentives to making data accessible’. In particular, there is a lack of incentive for researchers to deliver good data-sharing practices, as they are not recognised or rewarded for the effort involved. The benefits are not made obvious, and it is apparently hard to provide such incentives. Also, when researchers join a project at a later stage, they may not be familiarised with the vision of data sharing that has been established, and yet they are the ones that will often be responsible for documenting the work.

This lack of incentives also extends to the data management community. In situations where it is recognised that the scale of operation is sufficient to require specific data management expertise, funding/pay is often not sufficient to attract individuals with the required levels of skill, capability and commitment to the role. Where appropriate resources are put in place, the objectives of the data manager’s role need to be made clear. This could even extend to defining new variables in existing data sets.

Addressing these issues could potentially create greater clarity in the value of data sharing and encourage individuals to actively participate in the process. Alongside more incentives for data sharing, this will require senior researchers to provide leadership and promote good practice, supported by effective induction processes and training, to highlight the importance of data sharing to researchers and provide them with a supported process for effective delivery from the beginning of their involvement in a project.

Experience among stakeholders has also shown that the nature of the partners in a project can also have a significant impact on data sharing. There are many data types, individual preferences and a lack of standard data management practices between researchers. In some cases, there will be limited responsibility for data management processes in those partner organisations. On the other hand, when working with industry, there will often be a requirement for a non-disclosure agreement to be put in place.

Concerns around confidentiality or commercial interests can even lead to data providers removing elements from data sets or placing restrictions on the sharing of inputs and/or outputs of data-driven modelling exercises.

Again, data sharing agreements are important in resolving these issues and clarifying the relative value of the ‘data’, ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’ derived from a project. These will form part of an effective Data Management Plan that sets clear roles, responsibilities and expectations, addresses the concerns of commercial data owners, and clarifies specific data support needs.

Publishers also have a role to play in this process. They can provide additional incentives for data sharing by accepting ‘short/data papers’ or even publishing ‘data descriptors’ as a key output of a research project, rather than a by-product. This could incentivise researchers to publish their data.

3.3 Methods

Alongside the ‘resource’ and ‘people’ considerations, the discussion in the workshop identified the importance of the various ‘methods’ used to deliver consistent metrics and provide sets of data sharing principles that facilitate project comparisons. At their most effective these will be sympathetic to both quantitative and qualitative research traditions, recognising the significant challenge created by inter-disciplinary research where there can be multiple research approaches, data sources and repositories for data from the different communities and disciplines:

- In physical science and engineering disciplines, a key pillar is often that research is repeatable, leading to the question, ’Can we do a repeat test with the existing data?’

- Where modelling is an important element of the research process, model inputs and outputs can be equally important, as is the modelling process Where this modelling uses stochastic or tuning methodologies, it is not trivial to reproduce the outputs from the inputs and it may be necessary to store all the model outputs which can involve huge amounts of data. Development of training data sets can be important, as can version control for dependencies where open-source software is used.

- In the social sciences it may never be possible to repeat the experiment, and this will impact how long data needs to be There can also be uncertainty around factors inherent to the research process that prevent data from being shared and data sampling can be a problem.

Consequently, data sharing can mean different things to different disciplines, creating additional challenges when managing data in an interdisciplinary environment. Huge amounts of very different kinds of data can be produced and it is not possible to have a ‘one size fits all’ policy, creating difficulties in working to shared standards, that support cross-disciplinary access and use.

Collation of data within collaborative projects can also be a challenge, as collection criteria vary, and funders can require data to be deposited in a specific place. Key questions arise around what should happen to the data once a project finishes, and who should have access to it. Different disciplines and partner organisation answer these questions in different ways and also format and store their data differently.

Consequently, there is often ‘push back’ against storing data in multiple locations. Added to this, the rules for data access in some repositories can be seen as unnecessarily onerous.

Specific problems arise when handling data derived from mixed methods and/ or sensitive sources, particularly where consent not been secured or anonymising data is a problem. These problems are compounded where the data is in the form of transcripts – it may not be appropriate to share it all, but it is time consuming to make the necessary redactions. There can also be intangible data quality questions that are almost impossible to answer around how ‘well’ the data was collected.

Some of these issues can be addressed by referring to the ‘data / information / knowledge pyramid’ and re-visiting definitions of ‘data’ and ‘information’. Ethics processes are also important in supporting data sharing whilst regulating access to data and ensuring that confidentiality is not breached, using tools such as well-designed consent forms, impact statements and ethics declarations. Meta-data has a role to play here too, particularly when seeking to deliver against FAIR principles of data sharing.

However, the issues are not just about the creation of data sets but also the processes used for subsequent interaction with the data. There was a call for more analysis of when and how data needs to be accessed, a process which can be helped if the data sharing has a clearly defined purpose. The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre was highlighted as an organisation that had been particularly successful in this regard, and there are doubtless other useful case studies to be explored.

3.4 Technology

Finally, some consideration was given by workshop participants to the role of ‘technology’ in data sharing, although these considerations were relatively limited in their scope.

There was some discussion around how to ensure that data is secure when sharing across institutions, and the use of proprietary software like SPSS for making data sharable. However, the technical discussion mainly focused on the potential use of artificial intelligence approaches to make use of less organised data sets and the use of Large Language Models for data discovery.

4. Recommendations

To draw recommendations out of the above responses, participants were assigned to three new breakout groups. The main focus of this session was to reflect on learning points in Session 1 and to develop a list of priority recommendations to take forward. Groups also discussed the resources required to take the recommendations forward and the impact that they would have.

The outcome of these discussions is summarised below with more detail captured in Appendix 6.

- The data sharing experience of others is important – we need to secure better access to data for sharing, and make the methods, tools and guidance on how to do this more available. Energy consortia have a role in setting expectations and developing/pointing to resources.

- Providing metadata and good quality data indicators takes time. Managing data across multiple institutes, ethics teams and collaboration agreements can be complex. The different disciplinary domains common to energy consortia may have different standards that need to be All of these require expertise, attention and resourcing.

- Creating better data sets requires them to be more highly Institutions need to take the value of data more seriously, funding activities effectively, rewarding individuals for taking an active role, and recognising the importance of workload management. Energy consortia should help to set this framework as part of their culture.

- Data Management Plans are an essential starting point and should be in place at the beginning of However, to make most effective use of them, they should also be flexible, with appropriate mechanisms in place to reflect and learn as change occur.

- For large energy research centres in particular, proposals need to budget for a data manager, recognising that this is an important role requiring appropriate remuneration to secure quality personnel.

- Not all data are equal. The skills of the data manager should provide guidance and support to help discriminate between the value of different data sets and prioritise management effort accordingly.

- Skills and knowledge in the area of data management vary widely across the energy community, partly because of the involvement of so many different Training is required to improve researcher awareness of the value of data sharing and to improve their data management skills. Energy consortia can provide/ host this training and have a role to play here, emphasising the domain aspects of data management.

- A peer network for data managers and data stewards would be useful to enable sharing of best practice and identify areas to work on together to embed FAIR data and Open Research practices within researcher’s activities. Building on existing Energy Consortia collaboration activities, such as the Cross-Consortium Engagement Meeting (CCEM) would get this process started.

- The energy community is a large producer and user of models in a wide variety of areas and common standards for what to archive to enable FAIR data and reproducibility have not yet been agreed. Such protocols would be helpful to discuss. The energy research specific issues for sharing the outputs of energy models should continue to be highlighted.

Publication details

Colechin, M. and Quigley, C.. 2023. Improving data sharing in energy consortia: Summary of workshop outputs. CREDS Policy brief 031. Oxford, UK: Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions.

Banner photo credit: Alireza Attari on Unsplash