It’s rather unfashionable to say this, but UK climate policy is a success story. Emissions have fallen 43% below 1990 levels thanks, in part, to energy efficiency in the household and industrial sectors. However this success has a downside because cost-effective “low lying fruit” measures such as condensing boilers and double glazing that contributed to these reductions are reaching market saturation.

It’s rather unfashionable to say this, but UK climate policy is a success story. Emissions have fallen 43% below 1990 levels thanks, in part, to energy efficiency in the household and industrial sectors. However this success has a downside because cost-effective “low lying fruit” measures such as condensing boilers and double glazing that contributed to these reductions are reaching market saturation. The deeper cuts needed for the UK to meet its Paris Agreement target depend on trickier, more expensive technologies such as heat pumps and solid wall insulation.

So the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is looking at non-domestic buildings to help make up the shortfall. The sector has potential for significant cost-effective savings – enough to deliver the majority of BEIS’s 20% business energy efficiency target – and £6bn in energy and productivity savings – all by 2030. This would be the biggest single new measure in the government’s emerging programme. But there’s a reason why the sector has so much potential: extracting it is proving to be very difficult. Emissions from the sector are not coming down.

So why is the sector proving so hard to tackle? The answer is complex, but there are two key factors. First, to allow buildings to be compared, Building Regulations focus on the predicted energy performance of the building and its services, enshrined in the Energy Performance Certificate. However, in reality, buildings use energy for a wide range of activities: banking, healthcare, government, IT, hospitality, warehousing. This means that the real-world energy use can be out of line with the prediction, for example if an office is converted into a restaurant or a server farm.

This misalignment is known as the “performance gap” and can be very significant, with operational performance 50% lower than predicted. This matters because tenants can’t be sure that they will get an efficient building just by looking at the EPC. This dampens demand, and without demand, developers and investors are reluctant to invest to make the building efficient in the first place. The end result is a classic supply/demand breakdown, or “vicious circle of blame” where everyone blames someone else and nothing ends up being done.

A number of other countries have tried to tackle the problem by setting up dedicated operational ratings schemes, of which the best known is the National Australian Built Environment Rating System. NABERS is a 1 to 6-star energy performance rating that must be disclosed to tenants on sale or lease. The results are striking: NABERS is approaching market saturation with energy performance improving by 60% in 10 years. A typical office in Melbourne is up to 4 times as efficient as its equivalent in the UK. Crucially NABERS ratings are now used as an investment-grade asset performance benchmark.

Could NABERS work in the UK? The answer, from UCL research commissioned by BEIS in 2017, is that it might. Certainly the impact results are both compelling and material. The way the scheme works ties in with what change theory tells us about the sector. A number of leading UK developers are convinced enough to be trialling NABERS-like approaches. But what is not clear is how an operational ratings scheme would fit in the complex, and some would say dysfunctional, UK regulatory landscape. Solving this conundrum is a key CREDS research question.

The Australian government has invited UCL over to Sydney in the Summer of 2019 to study NABERS in more depth. Hopefully, by the Autumn, we will have some answers. Watch this space…

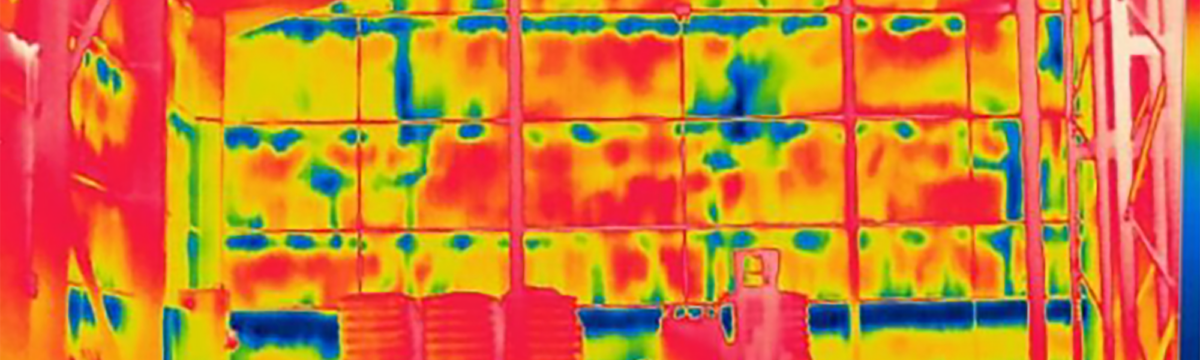

Banner photo credit: Артем Постоев on Adobe Stock