We spend most of our lives inside buildings, and the energy we use to light, heat and cool them is responsible for a third of UK CO2 emissions.

We spend most of our lives inside buildings, and the energy we use to light, heat and cool them is responsible for a third of UK CO2 emissions. So, now we need to take more action to tackle climate change and bring down emissions, and buildings are an important target for government policy.

Greener buildings also offer more than low carbon emissions. They cost less to run and can be more comfortable and quieter to live in, and healthier and more productive places to work. Increasingly, mortgage lenders, investors and insurance companies are factoring energy performance into their calculations. In fact, these non-energy, multiple benefits can easily outweigh energy cost savings.

However, the sheer diversity of our buildings, coupled with the complex way we use them, is a significant policy challenge that many governments are struggling with. In the UK, household energy demand was coming down until 2012, but then the government removed grants for energy saving measures from the so called ‘able to pay’ households, reducing installation rates by 95 per cent and stopping the energy efficiency market in its tracks. The Green Deal loan scheme, set up to replace these subsidies has become a case study in how not to do policy. When it was scrapped in 2015, only 14,000 of the target 14 million homes (0.1 per cent) had taken up loans for energy efficiency measures.

Commercial buildings need particular attention

The story on non-domestic buildings is, if anything, worse: energy demand from the services sector (which makes up around 90 per cent of the total) is actually ten per cent higher now than it was in 1970. This is, in part, because of the sheer variety of building types. Also, there is a ‘performance gap’: buildings don’t perform as efficiently in reality as they are designed to. Another challenge is the infamous landlord and tenant split, where owners and developers are reluctant to invest in energy efficiency because only the tenant benefits. Not surprisingly, the government is struggling to put any kind of coherent policy in place. In its flagship 2017 policy document, the Clean Growth Strategy, only four paragraphs were devoted to commercial buildings compared to 11 pages on households.

The silver lining to this lack of progress is that there is still a lot of low-lying fruit for new policies to go for. And the government, to its credit, is beginning to get its act together. In its latest policy statement, new policies for buildings dominate measures to meet the 20 per cent business energy efficiency target. BEIS has published a raft of consultations, mission statements and targets over the past 12 months. But once they’ve gathered all the evidence, what should be prioritised? What are the best policies and measures that should be put into place to cut the contribution of buildings to climate change?

Measuring actual performance

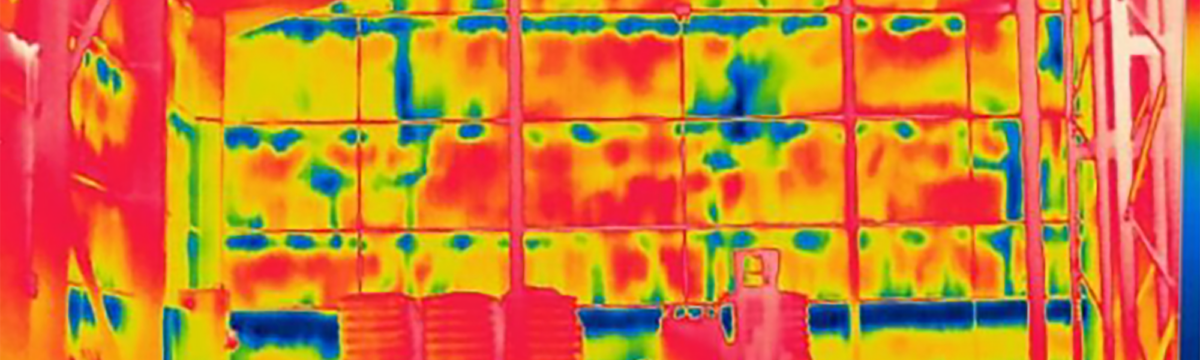

Perhaps the most important shift will be a move from predicted to operational energy performance standards. Currently policy focuses on ‘technology push’, predicting the performance of building fabric and services to comply with the Building Regulations and Energy Performance Certificates. This is a similar approach to the familiar appliance labels we see on fridges and TVs. But buildings are not fridges, because the way they are used in reality can increase energy use significantly, sometimes by as much as four times compared to the prediction. This is a bit like managing your finances without knowing how much you spend, or trying to lose weight without scales.

On the other hand, ratings, based on operational, in-use energy performance, work by giving occupiers the confidence that a building will work for them, rather than having to rely on a theoretical prediction. This creates demand for better buildings through ‘market pull’ which, in turn, stimulates developers to build more efficient buildings, and so on, creating a virtuous circle where suppliers react to higher demand, and users have a greater supply to choose from.

Learning lessons from abroad

Examples from abroad we can learn from include the Energy Star programme in the US, and the National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS). The Australian approach has been very effective: a typical office building in Melbourne can be four times as efficient as a comparable office in London. NABERS has also been studied extensively and could be particularly useful in informing a UK scheme, given the similarities between the UK and Australian markets.

Since CREDS wrote its Shifting the focus report, the government has announced it is considering moving to an operational ratings system for the UK, based on the Australian model, and it has promised to consult this summer on how this might work. But implementing such a system would be a significant challenge, given that the UK has used a predictive approach for so long. Also, the success of the Australian scheme relies heavily on mandatory disclosure by companies of the building’s performance, something that the UK has shied away from several times in the recent past because of concerns about placing unnecessary burdens on business.

The government should be congratulated for making a start. But the Australian system took 20 years to get right. Although we have the benefit of hindsight, the climate emergency means we don’t have anything like that long to get our buildings under control.

Report

Balancing the equation is a report by Green Alliance, based on CREDS research. A previous blog by the CREDS’ director Nick Eyre summarised the findings of the report.

Banner photo credit: VanveenJF on Unsplash