Richard Walker, Morgan Campbell, Greg Marsden, Shona McCulloch, Kay Jenkinson and Jillian Anable

Introduction

For the UK to reach its goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, all councils need to take rapid action to decarbonise their transport systems.

This will include action to support people to make their journeys by more carbon and space-efficient modes (such as walking, cycling, public transport and ride-sharing), and to support the take-up of zero tailpipe emission vehicles, for those journeys that will continue to require a motor vehicle.

However, shifting modes of travel is only part of the toolkit available to councils: transport can also be decarbonised by reducing the distances people have to travel, and the number of trips they have to make.

This briefing explores the potential of planning and design of the built environment to reduce the length of trips, and to make it possible for people to do more activities in one place (known as ‘accessibility planning’). Achieving this is key to making active and sustainable modes of transport competitive with the car.

Land use planning powers, accessibility planning, and design techniques to support transport decarbonisation are relevant both to the planning of new greenfield development and for the management of existing built up areas and their communities.

This briefing therefore touches on councils’ duties and powers as local planning authorities, local transport authorities, providers of local strategic leadership, and service providers.

Post-COVID-19, this subject is more vital than ever. There is also an opportunity: people used the period of lockdown to gain a renewed appreciation of facilities on their doorstep such as local shops and parks. However, people without access to a good mix of local facilities and who did not have access to a car lost out.

Accessibility planning for neighbourhood facilities might, therefore, be thought of also as part of councils’ resilience planning responsibilities.

Relevant policy strands

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) (2019) [1] sets out the Government’s planning policies for England and how they should be applied by local planning authorities. NPPF Chapter 9 Promoting Sustainable Transport sets out the planning policies related to this briefing.

The Department for Transport’s Cycling and Walking Plan for England (July 2020) [2] sets out ‘a bold vision for cycling walking’ with themes including ‘Putting cycling and walking at the heart of transport, place-making, and health policy’ and ‘empowering and encouraging councils’, including through £2 billion of new investment over the period 2020-25, ‘the great majority of which will be channelled through local authorities’.

The Government’s Housing Infrastructure Fund (HIF) is £4.1 billion of grant funding to fund infrastructure including roads and community facilities, allocated to councils on a competitive basis in the period 2018/19- 2023/24.

Neighbourhood plans are one element of a suite of powers for local communities in England provided for by the Localism Act 2011 which are potentially relevant to decarbonising transport through localisation, including designation of assets of community value. Both LGA and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) have published guidance on neighbourhood planning [15, 16].

Key facts

Reducing the distance people need to travel to access everyday facilities is an effective way to decarbonise transport. If the distance people need to travel to access schools, shopping, leisure, and recreation facilities is below one mile, then they are much more likely to access those facilities by walking [3].

Areas for action

All planning decisions matter for decarbonising transport. Although any given individual decision on a housing development or commercial site might seem small in terms of overall transport demand, every planning decision builds-in an inherent advantage to one kind of transport or another that lasts for decades.

The kinds of development being permitted give a very public signal about how seriously a council is taking the climate emergency. For a development to be truly low carbon, the strategic location, the layout and urban design, the land use mix and the transport provision need to be got right.

Major new workplaces and other trip generating developments must be located where they are easily accessible by active travel (cycling and walking) and public transport.

For local planning and transport to support carbon reduction there are three key areas of influence:

- spatial planning and land use planning

- ‘accessibility planning’

- attractive and liveable neighbourhoods.

Action Area 1: Getting spatial planning and land-use planning right

At the heart of using the planning system to reduce transport emissions is the need to make it easy for people to get to the facilities and places they want or need to visit.

The relative journey time of car and non-car modes is a key factor, but other factors have also been shown to increase the mode share of sustainable and active modes. For example:

- Mixing land-uses – making more services available in a locality [5]

- Designing developments to promote high quality walk and cycle facilities [6]

- Putting developments which lots of people use near good public transport (e.g. homes, shops, and offices) [7]

- Having an integrated approach to parking policy, recognising that the choice to drive relates to the ease of parking at home and at the destination [8]

- Building land-uses at higher density makes fulfilling the above goals much easier [9]

Putting things in the right place

Land allocations for developments that will attract large numbers of people should be placed at locations close to public transport stations.

Land allocations for developments such as industrial and logistics facilities, with high numbers of freight vehicle trips but low numbers of person trips, should be put at locations close to the strategic road network.

High density housing is best located close to rail or tram stations. Medium density housing and smaller workplaces are best located close to high quality bus corridors.

Research shows that building at density around good quality public transport in suburban areas reduces the likelihood of car commuting [10]. For example, Bath Riverside is a brownfield redevelopment site for new offices and housing, located 1 kilometre west of Bath city centre.

In addition to good walking facilities to Bath, and 14 different bus routes, every household is entitled to a variety of sustainable transport enticements. These include a free one-month bus pass, a free car club membership and a £100 cycle voucher. As of 2019, 70 per cent of new residents at the site use a form of sustainable mobility for their primary travel [11].

Getting parking right

A commercial development needs accessibility, and where this can be provided by walking, cycling or public transport then maximum parking standards are appropriate. Maximum parking standards set an upper limit for the number of parking spaces in a development.

In London, TfL have a clear system of parking standards related to the public transport accessibility level (PTAL) of the site. Maximum parking standards for residential developments are more complicated, but such standards can be made acceptable to residents through thoughtful planning and engagement.

For example, in Ørestad, Copenhagen, parking provision for all new homes is in a neighbourhood multi-storey car park owned by the public development corporation, integrated with a neighbourhood convenience store. The rent for parking spaces is used to fund upkeep of the public spaces and local community facilities. A companion briefing in this series covers parking in more detail [12].

Creative re-designation of land use High street retail has been in decline for a number of years, and this is accelerating following the coronavirus crisis. Office developments in city centres may be less sought-after following the shift to home working in formerly office-based employment as a result of coronavirus.

There are both good and very bad examples of re-purposing both office and retail space for new housing. Good examples include Ryedale House in York and the Broadwalk shopping centre in Edgware.

Recent proposed changes to permitted development rights will reduce the scope for planning authorities to influence the quality of developments. However, in terms of transport decarbonisation, an increase in town and city centre living is positive.

Ensuring the right design quality

There is a housing shortage in the UK and local authorities have stretching housing targets to meet. However, this does not excuse poor transport outcomes in new developments.

To meet new housing targets outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), new residential locations are often chosen based on how quickly these sites can be developed.

As discussed in the 2018 Transport for New Homes report [13], this approach inevitably leads to car-dependent communities. If a transport assessment is required of the developer, it is often limited to an impact assessment on road traffic nearby.

Furthermore, if road accessibility is not already present, developers can request government assistance to co-fund new roads. Such practices are inconsistent with the UK’s climate targets and increasingly at risk of legal challenge [14].

Instead, thoughtful design, which prioritises people over cars, can deliver sustainable, liveable, child-friendly developments. Such developments will include well integrated walking, cycling and public transport facilities, local food shops, and neighbourhood parks and green spaces [15].

Local plans and the climate emergency

All new build schemes being built in the 2020s must be compliant with a pathway to net zero carbon by 2050. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) places, amongst other things, a requirement on councils to mitigate climate change and move to a low carbon economy [16].

What might have passed as ‘sustainable development’ before the climate commitments set out in the Committee on Climate Change’s Net Zero report [17] will no longer suffice.

Local plans will need to be consistent with the carbon ambitions of the various climate emergency declarations and decarbonisation plans which both national governments and local authorities are committing to.

New local plans must be drawn up with this in mind, and existing plans may need to be revisited, or they may be subject to further challenge [18]. There is more limited capacity for councils to decline developments once they are agreed in the local plan.

Action Area 2: Planning existing places for accessibility and localisation

Using planning powers and techniques to deliver low-carbon living is not just about the design of new developments. It is also about the management of existing built-up areas and their communities.

The purpose of most trips people make is to access the activities they need or want to do: jobs, schools, healthcare, shops, leisure, and socialising. Providing good transport is one means of ensuring people get the accessibility they need, but it is not the only tool in the box.

Local government, as both the planning authority and service provider, can help ensure that everyday facilities are within easy walking or cycling distance for residents in existing communities: planning for attractive, liveable, and walkable local neighbourhoods.

Good for climate and communities

Although this briefing focuses on the advantages of walkable neighbourhoods for decarbonising transport, the benefits to communities are much wider.

Co-benefits include better public health (through better air quality and the physical and mental health benefits of more exercise), stronger communities, and lower levels of noise [19].

The coronavirus lockdown brought home how important it is to be able to access everyday needs locally, as well as how difficult life is when key services and facilities are not within easy reach.

This includes not only access to shops, schools and health centres, but also, for example, easy neighbourhood access to parks and green spaces for recreation and exercise.

Neighbourhood accessibility planning

Neighbourhood planning “gives communities direct power to develop a shared vision for their neighbourhood and shape the development and growth of their local area” [20].

In England, the term is mostly used in the context of the powers created by the Localism Act 2011 for parish councils and designated neighbourhood forums to prepare statutory Neighbourhood Plans and put them to a local referendum.

The Local Government Association’s Planning Advisory Service (PAS) has produced detailed guidance for councils on this agenda [21]. New development is usually the thorniest issue in neighbourhood planning, but its scope can be wider.

Accessibility planning is “the process of ensuring that responsibilities are clear for ensuring that all people can get access to essential services. Accessibility planning checks that needs are being met and organises solutions to the identified problems” [22].

Accessibility planning was a key principle in the government’s guidance for the second round of local transport plans (2006–11) and was related to the agenda for addressing social exclusion [23].

The next step is for accessibility planning to be joined up with local neighbourhood planning. With its potential to decarbonise everyday access to facilities in a way which responds directly to the needs and aspirations of communities, neighbourhood accessibility planning is a win-win approach which is already available.

The concept of the “20-minute neighbourhood” as a long-term planning strategy has been proposed as an alternative to car-dependency. This is the vision of neighbourhoods where people’s daily needs are within a 20-minute walk of their home [24].

Part of this agenda is about maintaining and enhancing local facilities in existing neighbourhoods. However, it also recognises that the vast majority of developments built in recent decades favour access by car.

Accessibility planning for decarbonising transport, therefore, is also about organising transport solutions to existing accessibility challenges. Councils are naturally at the centre of an approach that joins up land use planning, local transport planning and the provision of local public services.

Positive examples of councils tackling accessibility

The Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040 puts “integration at the heart of its strategy”, aiming for “maximising choice and supporting low-car lifestyles, made possible by integrated land use and transport planning”.

This involves putting improving the quality of life for residents through “connected neighbourhoods” on an equal footing with other concerns and is backed by a major increase in investment in local walking and cycling facilities [25].

In Liverpool, the Royal Liverpool Hospitals NHS Trust had proposed moving out of the city centre to an edge-of-town location as part of its major redevelopment plans.

Liverpool City Region’s transport body Merseytravel used accessibility planning analysis techniques to show that the additional costs of the move in terms of reduced accessibility and transport impacts would exceed the savings, and the decision was taken to redevelop the hospital complex into a new, world class health and academic precinct on its existing city centre site [26].

The Mayor of London’s Transport Strategy has set the target of 80 per cent of all trips in the city to be made on foot, by cycle or using public transport by 2041 [27]. To do this, it has put “the healthy streets approach” at the heart of the strategy [28].

The Mayor of Paris has recently introduced the policy of “Paris: ville du quart d’heure” – the 15-minute city. All services and activities fundamental to wellbeing will be accessible within 15 minutes by walking, approximately three quarters of a mile. Key to realising the 15-minute city is making sure that there is a good mix of services and very high-quality walking and cycling access [29].

The 20-minute neighbourhood standard has been adopted in Melbourne, Australia, where two pilot projects have been under way since 2018 [30].

Plymotion is a council initiative to make it easier for residents to get around Plymouth by sustainable modes. Key to this initiative is offering residents the opportunity to work with a travel advisor to rethink regular journeys and how to make them more sustainable.

Part of this is learning more about what can be accessed where. Preliminary assessments of the four-year initiative (2017–2021) show neighbourhood impact: residents are walking and cycling more for local journeys [31].

Conclusion

Planning for localisation and accessibility is something which every council can influence to help address the climate emergency. Putting new developments in accessible locations which are well designed and accessible to people’s every day needs is key.

Having a good range of facilities located within one to five miles of residential neighbourhoods makes it much more likely that people will travel by active modes. Compact neighbourhoods also make it easier to deliver transport interventions such as bike lanes, which encourage more people to take up cycling [32].

Building development which is less car- dependent matters for delivering on our climate commitments, but it also matters for people.

Given the option, most people prefer greener and more liveable neighbourhoods. Space that is not given over to the car can be used to create nicer places to live, play and exercise.

Places which do not require a car to access everyday opportunities are also more inclusive and resilient [33]. Recent work has shown that, too often, our planning system does not yet deliver these kinds of outcomes [34].

The climate emergency demands a more ambitious approach from councils, working together with developers to deliver a zero-carbon future.

Notes

This briefing is part of a series written for the Local Government AssociationOpens in a new tab (LGA) and was first published on their website.

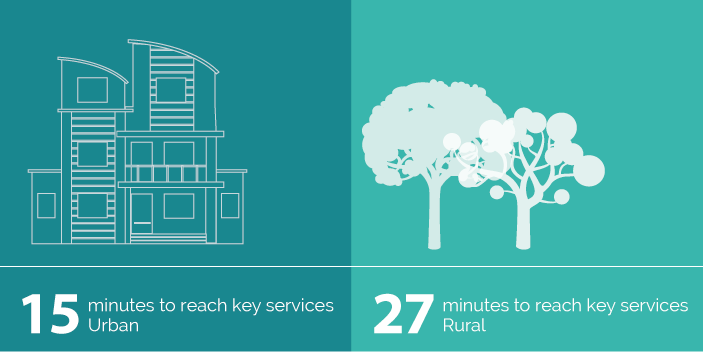

Figure 1: In urban areas, it takes an average of 15 minutes to reach key services such as schools, shopping and recreation facilities, whereas in rural areas it takes an average of 27 minutes.

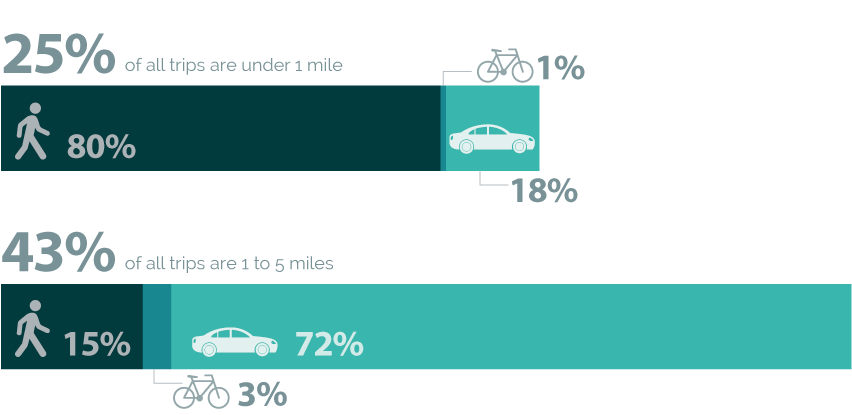

Figure 2: In England, 25 per cent of all trips are less than a mile. 80 per cent of these short trips are made on foot, 1 per cent by bicycle and 18 per cent in a car. 43 per cent of all trips are between 1 and 5 miles, 15 per cent are taken on foot, 3 per cent any bicycle and 72 per cent by car.

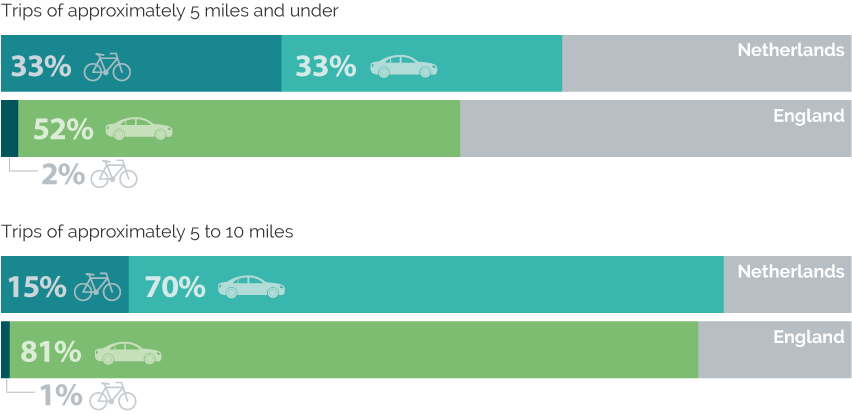

Figure 3: In the Netherlands, 33 per cent of trips of 5 miles and under are taken by bicycle, 33 per cent by car. In England, only 2 per cent of trips less than 5 miles are taken by bicycle, with 81% by car. For longer trips between approximately 5 and ten miles, in the Netherlands 15 per cent are taken by bike, with 70 in the car. In England, only 1 per cent of such trips are made by bicycle, with 81 per cent made by car.

References

- MHCLG (2019). National Planning Policy FrameworkOpens in a new tab

- Department for Transport (2020). Gear Change: a bold vision for cycling and walkingOpens in a new tab

- Ewing, R. and Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association. 76 (3): 265-29

- Harms, L. and Kansen, M. (2018). Cycling FactsOpens in a new tab Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis.

- Hickman, R., Seaborn, C. Headicar, P., Banister, D. (2010). Planning for Sustainable Travel: Integrating spatial planning and transport. In: Integrated Transport: From Policy to Practice. Ed. Givoni, M and D. Banister. New York: Routledge.

- Department for Transport (2007). Manual for Streets, pdfOpens in a new tab (146 pages, 4.8 MB). Thomas Telford Publishing.

- Ewing, R. and Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association. 76 (3): 265-29

- Christiansen, P. et al (2017). Parking facilities and the built environment. Transportation Research Part A, 95: 198-206.

- Ewing, R. and Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(3): 265-29

- Tennøy, A. (2018). Less car dependent cities: Planning for low carbon in Oslo, pdfOpens in a new tab (31 pages, 4.3 MB).

- ARUP (2020). You’ve declared a climate emergency. Next steps: transportOpens in a new tab

- Campbell, M., Marsden, G., Walker, R., McCulloch, S., Jenkinson, K., and Anable, J. (2020). Decarbonising transport: climate smart parking policies. Local Government Association: London.

- Transport for New Homes (2018). Transport for New Homes reportOpens in a new tab

- Client Earth (2019). Lawyers put local authorities on notice over climate inaction.

- Transport for New Homes (2020). Garden Villages and Garden Towns: Visions and RealityOpens in a new tab

- MHCLG (2019). National Planning Policy FrameworkOpens in a new tab

- Committee on Climate Change (2019). Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warmingOpens in a new tab

- Client Earth (2019). Lawyers put local authorities on notice over climate inaction.

- Karlsson, M., Alfredsson, E. and Westling, N. (2020) Climate policy co-benefits: a review. Climate Policy, 20 (3): 292-316

- MHCLG (2020). Guidance: Neighbourhood PlanningOpens in a new tab

- Local Government Association (2016). Neighbourhood PlansOpens in a new tab

- Halden, D. (2012) Integrating transport in the UK through accessibility planning. In: Accessibility Analysis and Transport Planning. Ed. Geurs, K., krizek, K. and Reggiani, A. Edward Elgar Publishing, 245-262.

- Kilby, K. and Smith, N. (2012). Accessibility Planning Policy: Evaluation and Future DirectionsOpens in a new tab

- Sustrans (2019). Why we are calling for 20-minute neighbourhoods in our General Election 2019 manifestoOpens in a new tab

- Transport for Greater Manchester (2017). Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040Opens in a new tab

- International Transport Forum. (2019). Improving Transport Planning and Investment Through the Use of Accessibility IndicatorsOpens in a new tab

- Greater London Authority. (2018). The Mayor’s Transport StrategyOpens in a new tab

- Transport for London. (2017). Healthy Streets for London ToolkitOpens in a new tab

- O’Sullivan (2020). Paris Mayor: It’s Time for a ‘15-Minute City’Opens in a new tab Published online at Bloomberg CityLab, 18 February 2020.

- Plan Melbourne 2017-2059. 20 Minute NeighbourhoodOpens in a new tab (opens in new tab).

- Plymouth City Council. Welcome to Plymotion

- Lokesh, K., Marsden, G., Walker, R., Anable, J., McCulloch, S., and Jenkinson, K. (2020). Decarbonising transport: growing cycle use. Local Government Association: London.

- Mattioli, G., Philips, I., Anable, J. and Chatterton, T. (2019). Vulnerability to motor fuel price increases: Socio-spatial patterns in England. Journal of Transport Geography, 78: 98-114

- Transport for New Homes (2018). Transport for New Homes reportOpens in a new tab

Publication details

Campbell, M., Walker, R., Marsden, G., McCulloch, S., Jenkinson, K., and Anable, J. (2020). Decarbonising transport: the role of land use, localisation and accessibility (opens in a new tab). Local Government Association: London. Open access

Banner photo credit: Alireza Attari on Unsplash