Donal Brown, Christian Jaccarini, Timothy J Foxon, Giulia Mininni, Claire Copeland, Marie Claire Brisbois, Siobhan Stack-Maddox, Beatriz Aguirre Martinez and Max Lacey-Barnacle

On this page:

- Foreword

- Executive summary

- 1. Context

- 2. Achieving net-zero: local goals, local delivery

- 3. What are Local Green New Deals?

- 4. Putting regions centre stage: Greater Brighton & North of Tyne

- 5. Citizen engagement: do local people want a Green New Deal?

- 6. Delivering Local Green New Deals

- 7. Ensuring economic and social justice in Local Green New Deals

- 8. Conclusions

Foreword

It’s a challenging time to be working on the climate and nature emergency. While droughts, heatwaves and floods escalate around the world, the UK government doubles down on its plans for new fossil fuel production. As people call in increasing numbers for clean air, affordable energy and a liveable future, the Prime Minister tells us that the ‘proportionate’ thing to do is to slow down climate action.

Yet, despite the lack of leadership from central government, some local authorities and regional leaders have been stepping up and offering a glimpse of what is possible – as this report so powerfully demonstrates. From Greater Brighton to North of Tyne, it’s exciting to see the potential and the appetite for local Green New Deals.

One of the most striking revelations in this report is the overwhelming popularity of the policies that were put to residents. This reinforces what Green New Deal advocates have been saying for years: if we design it right, climate action is win-win. Local Green New Deals will create jobs, deliver warmer homes and lower energy bills, and make our neighbourhoods more pleasant places to be.

So what does getting the design right look like? Fairness was a key theme raised by research participants, who were particularly concerned about the availability and quality of jobs. A true Green New Deal has social justice at its heart, as well as cutting carbon, so it’s essential that local Green New Deals retain wealth in the local economy and prioritise public services like buses and childcare.

It’s notable for a report on local action that virtually all the recommendations here are for central government. This speaks to the extraordinarily centralised nature of power in the UK, and the need to devolve powers and resources to local authorities so that they can get on with the job.

In my role as co-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on the Green New Deal, I have heard from local government and community leaders doing all kinds of inspiring work to help people and nature to thrive. Again and again, we hear that local areas know what needs to be done – but a lack of resources and lack of support from central government is holding them back. That urgently needs to change.

I thank the New Economics Foundation and the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions for this important contribution to public discussion of the Green New Deal. I look forward to raising its recommendations in Parliament as I and my cross-party colleagues continue our efforts to make the Green New Deal a reality at every level of government.

Caroline Lucas, Member of Parliament for Brighton Pavilion

Executive summary

In this report, we outline a transformative plan for how local and regional action could help to achieve the UK’s net-zero climate goals, whilst providing economic, social and environmental benefits to citizens – Local Green New Deals. The report argues that local and combined authorities should be given new powers and funding, and create new institutions to deliver measures that would help to reduce energy usage (or demand). It also provides evidence that these measures would be viewed favourably by the majority of citizens. We focus on two contrasting regions, Greater Brighton and North of Tyne – both having recently put forward progressive programmes for local environmental and social action, but with very different local governance arrangements.

What are Local Green New Deals?

We build on research from the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions (CREDS) showing how the UK could meet net-zero via measures that reduce energy use by 50% or more by 2050, whilst maintaining or enhancing citizens’ quality of life. Presenting new empirical research examining citizen preferences in two UK regional case studies, the report demonstrates high levels of public support for measures to address climate and economic challenges, while delivering social, economic, and environmental justice. When considering areas of policy that could be delegated locally, we argue four key objectives should be a major focus for developing Local Green New Deals:

- Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes: area-based retrofit programmes should ensure all homes meet a decent standard of energy efficiency, with funding for low-income households and local one-stop shops to support delivery in each neighbourhood. Support for the adoption of low-carbon heating technologies should also be greatly expanded.

- Affordable, sustainable public transport: access to public transport must be greatly improved to support a reduction in car use. This will require the expansion of bus routes, new light rail and train services and the electrification of these systems. Moreover, the current expensive, fragmented, and privatised model of public transport provision is unlikely to be compatible with these aims.

- Car-free city centres and active travel: urban centres which are free of traffic, pollution and noise are better and safer places. Alongside expanded public transport provision, car-free zones, extensive active travel routes and walkable towns and cities are key components of improving local health and wellbeing while meeting net-zero goals.

- Expanding green spaces and nature restoration: nature-based solutions are a critical means of sequestering carbon and addressing wider environmental issues such as air pollution. Additionally, by greatly expanding wild spaces, citizens can enjoy the benefits of spending time in nature and restore the UK’s depleted biodiversity.

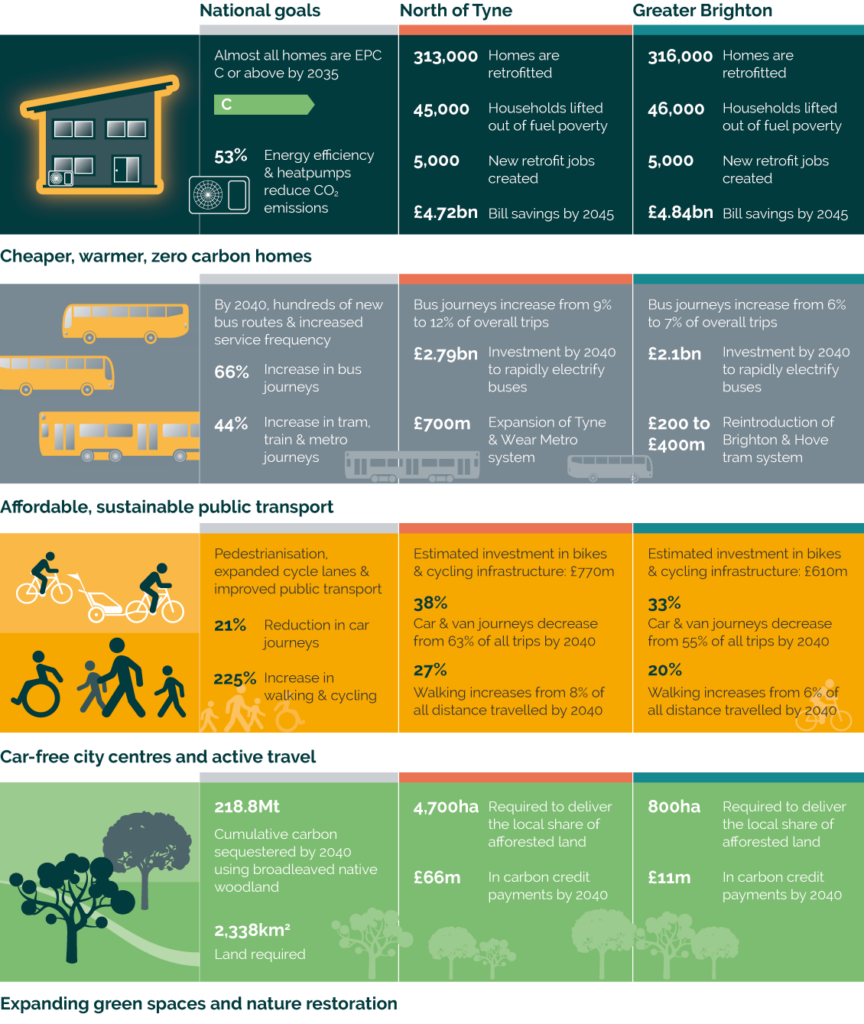

Figure image description

- Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes – National goals: Almost all homes are EPC C or above by 2035; Energy efficiency and heat pumps reduce CO2 emissions by 53%; North of Tyne: 313,000 homes are retrofitted, 45,000 households are lifted out of fuel poverty, 5,000 new retrofit jobs are created, combined all leading to bill savings of £4.72bn by 2045; Greater Brighton: 316,000 homes are retrofitted, 46,000 households are lifted out of fuel poverty, 5,000 new retrofit jobs are created, combined all leading to bill savings of £4.84bn by 2045.

- Affordable, sustainable public transport – National goals: By 2040, hundreds of new bus routes and increased service frequency, 66& increase in bus journeys, 44% increase in tram, train & metro journeys; North of Tyne: bus journeys increase from 9% to 12% of of overall trips, £2.79bn invested by 2040 to rapidly electrify buses, £700m expansion of Tyne & Wear Metro system; Greater Brighton: bus journeys increase from 6% to 7% of of overall trips, £2.1bn invested by 2040 to rapidly electrify buses, £200 to 400m to reintroduce the Brighton & Hove tram system.

- Car-free city centres and active travel – National goals: pedestrianisation, expanded cycle lanes & improved public transport, 21% reduction in car journeys, 225% increase in walking & cycling; North of Tyne: Estimated investment in bikes & cycling infrastructure £770m, car & van journeys decrease from 63% of all trips to 38% by 2040, walking increases from 8% of all distance travelled to 27% by 2040; Greater Brighton: Estimated investment in bikes & cycling infrastructure £610m, car & van journeys decrease from 55% of all trips to 33% by 2040, walking increases from 6% of all distance travelled to 20% by 2040.

- Expanding green spaces and nature restoration – National goals: Cumulative carbon sequestered by 2040 using broadleaved native woodland 218.8Mt, 2,338 square km land required; North of Tyne: 4,700ha of land required to deliver the local share of afforested land, £66 m in carbon credit payments by 2040; Greater Brighton: 800ha of land required to deliver the local share of afforested land, £11 m in carbon credit payments by 2040.

These measures are popular with citizens

Local Green New Deals should involve citizens in the decision-making process for introducing these measures. We undertook citizen engagement in both the North of Tyne and Greater Brighton regions. Firstly, in surveys, over 600 people were asked to assess their approval of 14 climate mitigation options, and choose their top 3 measures, in relation to a set of 20 wellbeing indicators. Survey responses in both regions were very similar, with affordable public transport, sustainable construction materials and home energy efficiency being the most popular measures. Plant-based diets, car-free zones and car sharing were less popular, though still largely viewed favourably. In both areas, respondents preferred increased central government funding for local government, above council tax increases. The novel option of funding these options via municipal climate bonds was as popular as the UK government’s current competitive bidding approach.

Secondly, we carried out focus groups with 25 participants in each location to examine 6 policy areas in more detail: home energy efficiency; affordable public transport; active travel; car-free zones; nature-based solutions; and plant-based diets. This provided quantitative findings from participants, using a detailed Multicriteria Mapping (MCM) methodology, as well as qualitative insights from group discussions. In Brighton, affordable public transport, nature-based solutions, and active travel received the highest scores, with the average score for all 6 options higher than 50 out of 100, but with considerable variation between participants. In North of Tyne, most options had a higher average positive approval score, except for subsidised plant-based diets. While the presented options were generally viewed favourably, how they are implemented mattered to the participants. Critical themes which emerged from the discussions were: 1) fairness, including distribution and access; 2) affordability and reliability of services; 3) physical and mental health; and 4) environmental protection.

Delivering Local Green New Deals

Building on the findings from the citizen engagement exercises and previous analysis of low energy demand pathways, we analyse the scale of action needed in these four policy areas for the two regions, and develop Local Green New Deal policy proposals to achieve this. We outline a series of recommendations for an increased role for local government across three domains: 1) New institutions for delivery, 2) New powers, and 3) New funding.

We propose that a Local Green New Deal for a UK region should consist of the following:

Cheaper, warmer, lower carbon homes:

A national retrofit programme would see almost all homes meet EPC ‘C’ standard or above by 2035, with the deployment of energy efficiency improvements including heat pumps delivering a 53% reduction in home CO2 emissions. In both North of Tyne and Greater Brighton, this would see over 310,000 homes retrofitted, requiring around £2.9bn of public and private capital investment. Due to the much higher prevalence of low-income households in North of Tyne, the level of public investment needed is much higher (£1.04bn) than in Greater Brighton (£286m). In each location, delivering on this ambition creates over 5,200 construction jobs, and by 2045 leads to over £4.7bn in energy bill reductions – saving the average household £779 a year and lifting over 45,000 households out of fuel poverty.

New institutions for delivery:

- A 10-year Local Retrofit Delivery Framework supporting regions to set up a Retrofit Taskforce and local one-stop shops, with central government expertise and leadership to support implementation.

- A nationwide citizen engagement campaign, supporting councils and community groups to engage the public with the retrofit challenge.

- Establish new training courses and apprenticeships for retrofit tradespeople, costing £400m nationwide.

New powers:

- Most retrofit and fuel poverty programme delivery to be devolved to local and combined authorities.

- Reintroduce Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) and strengthen enforcement powers.

- Amend legislation to allow for the introduction of Property-Linked Finance, so that the UK can fully leverage private investment.

New funding (UK wide):

- UK government devolves £2bn to the Local Retrofit Delivery Framework.

- UK government devolves £48.5bn low-income building fabric grants with £9bn available for a heat pump boiler scrappage programme, and £4.5bn ringfenced for low- income households.

- Develop a blended financing offer, combining grants and low-interest loans, based on household income, with repayments tied to the property not the individual.

Affordable, sustainable public transport:

By 2040, thousands of new bus routes are developed and the frequency of existing services increases, with bus journeys increasing by 66%. A 44% increase in tram, train, and metro journeys is achieved, and buses are rapidly electrified. This requires £2.79bn investment in North of Tyne and £2.1bn in Greater Brighton by 2040. Buses’ relative composition of all journeys grows from 9% to 12% in North of Tyne and 6% to 7% in Greater Brighton.

Further specific investments would be a significant £700m expansion of the Tyne and Wear Metro system, and the reintroduction of a tram system in Brighton and Hove at a cost of between £200-400m, based on systems in similar UK cities.

New institutions for delivery:

- Establish central advisory bodies with expertise on bus and rapid transit.

- Review the functional geography of transport authorities.

- Integrate rail planning with local and regional transport planning.

- Local governments establish wholly owned arm’s length development companies.

New powers:

- Give control over buses to all transport authorities.

- Lift the ban on municipal ownership of bus operators.

- Move towards a not-for-profit system of bus services.

- Devolve the powers for setting up a light rail system to local government and establish trailblazer cities for integrated public transport.

New funding (UK wide):

- Invest around £37bn nationwide to expand and decarbonise bus services and £7bn in local rail by 2040.

- Give local areas the ability to tax large local employers for rail infrastructure, following London and the Crossrail example.

- Strengthen current mechanisms for capturing land value uplift, and reform the land development process to deliver increased revenues for councils.

- Reform appraisal tools for large capital projects, to better value environmental and social benefits.

Car-free city centres and active travel:

City centres are pedestrianised, cycle lanes are greatly expanded, and high streets are favoured above out-of-town shopping. When combined with improved public transport, this leads to a 21% reduction in car journeys and a 225% increase in walking and cycling. By 2040, car and van journeys decrease from 63% of all journeys in 2022 to only 38% in North of Tyne, and from 55% to just 33% in Greater Brighton. These changes enable walking to increase dramatically from 8% of all distance travelled to 27% by 2040 in North of Tyne, and from 6% to 20% in Greater Brighton. Cycling also increases from just 2% of distance travelled to 6% in both regions, requiring substantial investment, with an estimated £770m invested in bicycles and cycling infrastructure in North of Tyne and £610m in Greater Brighton.

New institutions for delivery:

- Central government lays out a clear vision for low-traffic town and city centres.

- National Highways are required to work with local government to tackle emissions.

- Empower and fund local development corporations to develop transport-led housing.

New powers:

- Low-Traffic Neighbourhoods are made less difficult and expensive to implement.

- Strengthen local government tools to promote safer cycling.

New funding (UK wide):

- Review and reform taxes and charges on roads and parking.

- Devolve and pool local authority transport funding to provide longer term certainty.

- Radically reform appraisal tools for large capital projects, to properly capture the benefits of active travel and public transport.

Expanding green spaces and nature restoration:

To deliver improvements in access to nature and biodiversity, nature-based solutions are promoted in preference to bioenergy power plants with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). By 2040, a cumulative 219 Mt of carbon is sequestered nationally using reforestation and new wild spaces, covering 233,800 hectares (Ha) or around 0.96% of the UK’s land area. Delivering North of Tyne’s share of afforested land would require a total of 4,709 Ha of reforested area, with the vast majority in Northumberland. Using carbon credit payments, this would cost around £66m by 2040. Greater Brighton’s smaller suitable landmass means its share of this afforestation programme is much smaller – a total of 807 Ha. Using carbon credit payments, this would cost around £11.3m by 2040.

New institutions for delivery:

- Create a national Land Use Framework that amends property rights such that landowners must comply with agreed uses for agricultural and rural land.

- Explore establishing a Bank of England-funded land bank to support landowners struggling to make changes to their land.

- Reform UK food systems to empower farmers to take better care of their land.

- Make the Land Register free to access for all.

New powers:

- Empower local government to create Local Nature Recovery and Local Land Use Planning Strategies, and to designate areas as part of a Nature Recovery Network.

- Assign new powers to National Park Authorities to drive nature recovery.

- Give the Forestry Commission a new statutory duty to promote nature recovery and support net-zero.

New funding (UK wide):

- Shift agricultural subsidies to reward farmers for increasing biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

1. Context

The UK is attempting to address the climate emergency in the face of rising inequality and stagnant economic growth. Whilst this requires significant investment in innovation and the deployment of renewables, it also requires measures which reduce energy demand and deliver social and economic benefits. Most of these demand reducing measures need to be locally devised and delivered. This report examines the potential for the implementation of these measures at a local and regional level, building on CREDS research showing how the UK could meet net-zero greenhouse gas emissions (Barrett et al, 2021). Presenting new findings from engagement with citizens in two UK regions – Greater Brighton and North of Tyne – the report demonstrates high levels of public support for ‘Local Green New Deals’ (New Economics Foundation, 2023) to address climate and economic challenges. Developed in partnership with the New Economics Foundation (NEF), the report makes policy proposals for how Local Green New Deals could deliver the social, economic, and environmental transformation needed to achieve net-zero. This will require local and regional combined authorities to be given the appropriate powers, funding and supporting institutions, alongside public engagement to ensure fairness and affordability. Drawing on the two contrasting regions of the North of Tyne and Greater Brighton, this report sets out a template for how Local Green New Deals could be achieved.

The four pillars of a Local Green New Deals framework that we explore are:

- Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes

- Affordable, sustainable public transport

- Car-free city centres and active travel

- Expanding green spaces and nature restoration

In Section 2, we introduce Green New Deals and the need for local delivery to meet climate emergency goals. In Section 3, we outline how achieving locally conceived and democratically delivered Green New Deals can help to reach these goals by reducing energy demand whilst maintaining or enhancing citizens’ quality of life. Section 4 introduces the reasons why our two case study regions, Greater Brighton and North of Tyne, are of particular interest. Section 5 summarises our primary research with the citizens of the North of Tyne and Greater Brighton, which demonstrates the popularity of Green New Deal measures across the demographic spectrum, whilst highlighting issues to be addressed in their implementation. Section 6 then outlines our detailed policy proposals across four key areas of policy: cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes; affordable, sustainable public transport; car-free city centres and active travel; and expanding green spaces and nature restoration, providing a series of policy recommendations on how national government can support local and regional government in this agenda. Section 7 discusses how to ensure economic and social justice in Local Green New Deals. Section 8 provides summary conclusions.

2. Achieving net-zero: local goals, local delivery

The UK, Scottish and Welsh parliaments and multiple local and regional authorities have all voted to declare a ‘Climate Emergency’. This follows a global movement that emerged from social pressure and discontent with the lack of climate action within governments, industries, and businesses.

In a recent appraisal of the UK’s progress towards reaching its net-zero target, the Climate Change Committee finds that more than half of the emissions reduction needed must now come from citizens adopting low-carbon technologies and lifestyles (CCC, 2021). They further note that 30% of reductions depend on actions that involve local authorities, and that they have a significant degree of influence over other potential reductions. Increasingly, climate action is focusing more on regional and local scales and is taking a more ‘place-based’ approach. A recent appraisal of the economic costs of net-zero across six city regions (Innovate UK, 2022) found that place-based delivery requires only 25% of the investment of a ‘place-agnostic’ approach, and creates about twice the level of energy cost savings and social benefits.

While the net-zero role of local and regional authorities is considered critical, powers to make policy decisions remains largely centralised, and austerity measures have reduced authorities’ capability and capacity to implement climate actions (Tingey and Webb, 2020). Nevertheless, local and regional authorities are developing innovative ways to use local investment projects, initiatives, and procurement frameworks to meet multiple objectives, including decarbonisation, providing quality jobs, reducing fuel poverty, and improving local wellbeing and economic competitiveness. Performance is, however, uneven, and this is resulting in rising inequality within and between locations (Gray and Barford, 2018). To overcome this, we propose Local Green New Deals as an overarching framework for achieving these aims.

The Green New Deal

Originally conceived by a group of UK economists and policy experts in the context of the climate emergency and 2008 financial crisis (Simms et al, 2008), the Green New Deal gained prominence via a group of progressive US politicians in 2019 (Senate of the United States, 2018). The idea of local action to promote a Green New Deal in the UK has recently been championed by an All-Party Parliamentary Group of MPs and Peers (The Green New Deal Group, n.d.). Work by the authors of this report (Brown et al, 2023) has identified five core elements of a UK Green New Deal:

- Financial reforms;

- Green infrastructure investment;

- Financing the green new deal;

- Ownership structures;

- Economic, social and climate justice

The research notes that while some elements of the Green New Deal require national and international action, much of the implementation will be local in nature. Indeed, this drive for locally coordinated and delivered solutions is already being taken up by several local and regional authorities. For example, in 2021, the North of Tyne Combined Authority established a ground-breaking £18m Green New Deal investment fund (North Tyne Combined Authority, 2021a) to tackle carbon emissions whilst delivering inclusive economic growth. In 2023, Brighton and Hove City Council set out plans for a Green New Deal, proposing a £3.9m investment in public transport, an insulation programme, developing the circular economy, and massive investment in renewable energy across the region. These ideas are also supported by the Greater Brighton City Economic Board, which covers seven local authority areas, from Bognor in the west to Seaford in the east, and Crawley in the north of Sussex. Both plans emphasise that tackling the climate crisis is also the key to tackling the economic crisis.

However, local plans to move further and faster than the UK government in tackling the social, economic, and environmental crises are hampered by the UK’s overly centralised political system. Indeed, with few powers to enact transformative changes, the UK, and especially the English governance landscape, is among the most centralised in the developed world. By centralising powers in Westminster, the UK’s regions are being held back on their pathway to a low-carbon future which delivers economic and social prosperity. Despite 75% of District, County, Single-Tier Councils and Combined Authorities having declared a Climate Emergency (Gudde et al, 2021) (as of November 2021), few have the control over their public transport systems and the powers and resources needed to retrofit their housing stock or engage in nature restoration on the scale that climate change targets tell us is necessary.

In this report, we set out a plan for how policymakers could redress this imbalance through Local Green New Deals – empowering local areas to capitalise on the huge potential of a low-energy, low-carbon future.

3. What are Local Green New Deals?

Place-based design and delivery of net-zero measures is likely to lead to improved economic outcomes. In addition to the economic case, recent CREDS research on ‘Positive Low-Energy Futures’ (PLEF) (Barrett et al, 2022) has shown that energy demand reduction and transformation is critical for realising national net-zero emissions targets and has multiple societal and environmental benefits. This work showed that an aspirational ‘Transform’ scenario, consisting of a range of transformative measures to reduce energy demand, including significant improvements to the energy efficiency of housing and building stock, reduced car use and increased walking and cycling, could lead to a 52% reduction in final energy consumption by 2050, compared to 2020 levels. It argued that these measures could be implemented whilst maintaining or enhancing citizens’ quality of life by realising strong ‘co-benefits’, including healthier active lifestyles, lower airborne pollution, and an improved work-life balance. Moreover, many of these ‘demand-side’ actions tend to be implemented at a local government level.

When considering the areas of policy that are most appropriate to be delegated locally, we argue four key objectives should be a major focus for developing Local Green New Deals, as shown in Figure 1.

In this report, we adopt the ambitious targets from the PLEF ‘Transform’ scenario to inform the detailed policy proposals for Local Green New Deals across these four areas. In addition, we draw on other recent CREDS-supported research on a national home retrofit programme, Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes, and the CREDS Place-Based Carbon Calculator (PBCC) (PBCC, 2022).

Figure 1 image text

- Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes: Area-based retrofit programmes should ensure all homes meet a decent standard of energy efficiency, with funding for low-income households and local one-stop shops to support delivery in each neighbourhood. Support for the adoption of low-carbon heating should also be greatly expanded.

- Affordable, sustainable public transport: Access to public transport must be greatly improved if car use is to be reduced. This will require expansion of bus routes, new light rail and train services and the electrification of these systems. Moreover, the current expensive, fragmented, and privatised model of public transport provision is unlikely to be fit for these aims.

- Car-free city centres and active travel: Urban centres free of traffic, pollution and noise are better and safer places to be. Alongside expanded public transport provision, car-free zones, extensive active travel routes and walkable towns and cities are key components of improving health and wellbeing while meeting net-zero ambitions.

- Expanding green spaces and nature restoration: Nature-based solutions are a critical means of sequestering carbon and addressing wider environmental issues and air pollution. Moreover, by greatly expanding wild places, citizens can enjoy the benefits of spending time in nature and restore the UK’s depleted biodiversity.

4. Putting regions centre stage: Greater Brighton & North of Tyne

With steps towards English devolution, local and regional governments have become an increasing focus as an appropriate scale and geography to coordinate and deliver key elements of the net-zero transition. However, the changes to this governance landscape have not been even. While some regions, such as North of Tyne, have a Combined Authority with an elected Mayor and increased statutory powers, others, such as Greater Brighton, have only informal structures and few integrated powers. In examining Local Green New Deals, we explore these two contrasting regions – both having recently put forward progressive programmes for local environmental and social action. Below, we provide a summary of these proposals and briefly highlight the two regions’ economic, demographic and governance characteristics.

Greater Brighton

Brighton and Hove is on the southeast coast of England and has a population of over 270,000. The city is well known for its flourishing economy, its diversity and as a centre for innovation and enterprise (Brighton & Hove City Council, 2018). Brighton & Hove City Council (BHCC) is also known for its commitment to, and engagement with, sustainability. The Council declared a climate emergency in 2018, and through democratic consultations with their Climate and Youth Assemblies in 2020, developed a Carbon Neutral 2030 Programme. Its aim is to address poverty and inequality, and climate change, energy and decarbonisation initiatives. In 2020, BHCC also unanimously endorsed a motion to support a Green New Deal.

Greater Brighton comprises seven councils: Adur, Arun, Brighton and Hove, Crawley, Lewes, Mid Sussex and Worthing, with around 1 million inhabitants. Greater Brighton’s economy paints a contrasting picture between a growing qualified and prosperous core in Brighton & Hove and a less prosperous population in the periphery, with Brighton & Hove itself being one of the UK’s most unequal cities. Unaffordable housing, a relatively unskilled workforce, high youth unemployment rates, and infrastructural challenges, such as the road and rail networks, are currently hampering the region’s progress (Regeneris, 2018).

Formed in 2014, the Greater Brighton Economic Board (GBEB) is a critical player in promoting sustainability and tackling climate change. The Board is a legally constituted body overseeing the area’s economic growth and related activities. GBEB organised a Climate Summit in October 2021, elaborated a Blue/Green Governance and Investment Plan as part of a Transition to Net Zero Action Plan, and bids for central government funds for key actions, due to limited capacity at the regional level (Brighton & Hove City Council, 2021). However, unlike Mayoral Authorities, GBEB has few statutory powers and only an indirect governance and democratic structure.

North of Tyne

The North of Tyne region is located in the northeast of England. The North of Tyne Mayoral Combined Authority (NTCA) was formed in November 2018, following a devolution deal between the UK government and constituent local authorities: Newcastle City Council, Northumberland County Council and North Tyneside Council. The region therefore combines a densely populated city core with one of England’s most rural and sparsely populated counties – Northumberland. The devolved powers awarded to NTCA include funds for regional economic growth and jobs, and funding for adult education to develop local skills.

The North of Tyne region elected its first mayor, Jamie Driscoll, in 2019. In his manifesto, there were pledges to keep wealth generated within the region, stimulate a green industrial revolution, create community hubs, build affordable homes, and provide meaningful adult education (Driscoll, 2019). A ‘Local Green New Deal’ was part of delivering on these commitments, with ambitions to be a ‘zero carbon, zero poverty’ region (North of Tyne Combined Authority, 2022a). A 5-point plan was developed to achieve this vision (North of Tyne Combined Authority, 2022b).

In three years, NTCA have initiated a range of projects and programmes. The main ones are: the Green New Deal Fund, Climate Change Energy and Green Growth Blueprint, Technology Innovation and Green Growth for Offshore Renewables (TIGGOR) Programme and holding a Citizens Assembly on Climate Change. The North of Tyne Green New Deal Fund is an investment fund for low-carbon project support in the form of loans, equity and grants for SMEs, public sector organisations and community groups. The aim is to obtain match funding so that the £9m from NTCA becomes an £18m investment in the region. In addition, the funding criteria requires that every £4,525 of investment saves 1 tonne of carbon emissions per annum, and energy efficiency projects achieve a 10% energy cost reduction (North of Tyne Combined Authority, 2021b).

In December 2022, a new Devolution Deal was announced that will set up a new North East Mayoral Combined Authority, bringing together the three councils in the North of Tyne region with the four councils (Durham, Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland) currently constituting the North East Combined Authority. The new North East Mayoral Combined Authority will be constituted via elections in May 2024. In this report, all figures for the North of Tyne region relate only to the three council areas currently constituting the North of Tyne Combined Authority.

5. Citizen engagement: do local people want a Green New Deal?

Local Green New Deals should involve citizens in the decision-making process. To simulate this, in 2022-23, we undertook extensive citizen engagement activities in both the North of Tyne and Greater Brighton regions. We adopted a mixed method approach, combining quantitative survey data and qualitative data collection through two Multicriteria Mapping (MCM) workshops. The team elaborated this innovative research approach based on:

- Options for reducing energy demand whilst maintaining citizens’ quality of life, as shown in Table 1 (Based on the PLEF low energy demand ‘Transform’ scenario, see Barrett et al., 2022);

- Wellbeing Criteria to understand people’s priorities and values relating to social, economic, and environmental goals as shown in Table 2 (Based on the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the wellbeing framework in Creutzig et al. (2022));

Fourteen climate mitigation options were initially presented in a survey, in which respondents were asked to assess their approval of these options and choose their top three measures contributing to overall wellbeing, based on a set of 20 wellbeing indicators. From the survey findings, six mitigation measures were selected to be discussed in more detail in the focus groups – two of the most preferred, two mid-range and two least preferred measures, in relation to six selected wellbeing indicators – two economic, two social and two environmental (Table 2). Two focus groups were then held with 25 participants from each region, with one in Brighton and one in Newcastle, where participants were asked to score these measures according to their contribution to a set of wellbeing indicators, and then to weight the importance of those indicators, using a version of the MCM methodology (Stirling and Mayer, 2001).

| Options | Description |

|---|---|

| Home energy efficiency | 2,000 houses retrofitted to the Energy Performance Certificate ‘C’ * |

| Affordable public transport | 50% bus fare reduction |

| Active travel | Significant expansion of cycle-hire and bike lanes |

| Car-free zones | Extensive car-free zones to restrict driving through the town centre |

| Nature-based solutions | Substantial re-wilding of local countryside, new nature reserves |

| Plant-based diet | All public building and school meals vegetarian and dairy free |

| * The UK EPC provides a property with an energy efficiency rating from A (most efficient) to G (least efficient) with a validity of 10 years. | |

| Criteria | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Health benefits | Improved physical and mental health |

| Being part of a safe and supportive community | Increased community resilience and connection, improved protection from crime, access to community services for all | |

| Economic | Value for money | Optimising net social costs and benefits, increased benefits for all from public investment, public investments that consider both economic and social benefits, managing social and economic risks |

| Quality jobs creation | Creation of good quality, flexible and long-term jobs, fair pay and working hours, increased equality, diversity and inclusion, flexible and long-term opportunities to satisfy people’s working and life needs | |

| Environmental | Safe and clean local environment | Increased safety in local areas, cleaner local environment, access to safe, clean, green spaces for living, leisure, and outdoor play |

| Tackling climate change | Reduce CO2 emissions through reduced fuel and energy consumption, public and active transit, buying local products, increasing building energy efficiency, reducing consumption and recycling, reusing, and upcycling | |

Citizen survey

The team undertook a two-phase survey between June and September 2022. In the first phase from June to July, two researchers conducted a face-to-face survey with 46 residents in Brighton. To gain a higher number of responses, a second phase was conducted using a market research company to generate a range of online responses in the Greater Brighton (GRB) and North of Tyne (NoT) regions. This generated a further 566 respondents aged between 18-65+, giving a combined total of 612 respondents, of which 343 were in the Greater Brighton region and 269 in the North of Tyne region.

The figures below present the survey results for Greater Brighton and North of Tyne. In the first pair of figures, the respondents were asked about the extent to which they approve or disapprove of a range of energy demand mitigation measures. The patterns of responses in both regions are very similar, with affordable public transport, sustainable construction materials and home energy efficiency being the most popular measures. Car-free zones and car sharing were less popular, though still with net positive approval scores. Plant-based diets was the only option that had balanced positive and negative or net negative approval scores.

Figure 4 image description

People in Greater Brighton were asked if they strongly agree, approve, neither approve nor disapprove, disapprove or strongly disapprove of suggestions for reducing CO2 emissions. Over 60% of respondents strongly agreed with Affordable public transport, and 28% approved.

- Well over half of the respondents either strongly agreed or approved of Sustainable construction, Home energy efficiency, Community decision-making, Nature-based solutions, Active travel, and Park & ride options.

- Around half of respondents either strongly agreed or approved of Place-based solutions, Mobility hubs, Longer life foods / products & materials, and Cycling networks.

- For Car-free zones, almost 30% of respondents neither approved nor disapproved, with 16% disapproving of the option.

- For Car sharing, 41% of respondents neither approved nor disapproved. Plant-based diet was the least popular option, with 44% of respondents neither approving nor disapproving, 14% disapproving and 11% strongly disagreeing.

Figure 5 image description

People in North of Tyne were asked if they strongly agree, approve, neither approve nor disapprove, disapprove or strongly disapprove of suggestions for reducing CO2 emissions.

- 58% of respondents strongly agreed with Affordable public transport, and 33% approved.

- Well over half of the respondents either strongly agreed or approved of Sustainable construction, Home energy efficiency, Community decision-making, Nature-based solutions, Active travel, Park & ride, and Place-based solutions options.

- Around half of respondents either strongly agreed or approved of Longer life foods / products & materials.

- For Mobility hubs, and Cycling networks, just under half of the respondents either strongly agreed or approved.

- For Car-free zones, almost 30% of respondents neither approved nor disapproved, with 19% disapproving of the option. For Car sharing, 46% of respondents neither approved nor disapproved.

- Plant-based diet was the least popular option, with 38% of respondents neither approving nor disapproving, 19% disapproving and 17% strongly disagreeing.

Respondents were then asked to rank their Top 3 energy demand mitigation measures. Again, the response pattern in the two regions is very similar.

Figure 6 image description

People in Greater Brighton were asked to rank their top 3 energy demand mitigation measures from a list consisting of Household energy efficiency, Affordable public transport, Sustainable / recycled construction, Community engagement in decision-making, Nature-based solutions, Longer life food / products & materials, Active travel, Car-free zones, Cycling networks, Park & ride, Place-based solutions, Plant-based diet, Mobility hubs, and Car sharing.

- Household energy efficiency, and Affordable public transport were by far the most popular options, with 152 respondents ranking Household energy efficiency first, and 55 ranking it second most important. 67 respondents ranked Affordable public transport as most important, with 84 people ranking it second most important.

- Mobility hubs and Car sharing were the least popular, with only 1 and 4 votes at rank 1.

Figure 7 image description

People in North of Tyne were asked to rank their top 3 energy demand mitigation measures from a list consisting of Household energy efficiency, Affordable public transport, Sustainable / recycled construction, Community engagement in decision-making, Nature-based solutions, Longer life food / products & materials, Active travel, Car-free zones, Cycling networks, Park & ride, Place-based solutions, Plant-based diet, Mobility hubs, and Car sharing.

- Household energy efficiency, and Affordable public transport were by far the most popular options, with 127 respondents ranking Household energy efficiency first, and 39 ranking it second most important.

- 47 respondents ranked Affordable public transport as most important, with 67 people ranking it second most important.

- Mobility hubs, Plant-based diet, and Car sharing were the least popular, with only 0, 0 and 1 votes at rank 1.

Finally, respondents were asked about their preferences for four different funding mechanisms for implementing energy demand measures. In both cases, the results clearly show a preference for increased central government funding for local government, and little desire for increases in council tax. Interestingly, the option of municipal bonds, (where councils raise debt to fund climate mitigation measures) was as popular as the UK government’s current competitive bidding approach, despite being a relatively unknown concept in the UK.

Figure 8 image description

In Greater Brighton, the most popular mechanism for implementing energy demand measures was more central government funding for local authorities at 78%, with local council tax increases the least popular option at 10%. Both community municipal bonds and local authority competitive bidding approaches were selected by 40% of respondents.

Figure 9 image description

In North of Tyne, the most popular mechanism for implementing energy demand measures was more central government funding for local authorities at 80%, with local council tax increases the least popular option at 12%. Local authority competitive bidding approaches were slightly more popular (42%) than community municipal bonds (34%).

Qualitative insights from focus groups

While the presented options were generally viewed favourably, how they are implemented influenced which options participants valued for their and their communities’ wellbeing. Critical themes which emerged from qualitative analysis of participants’ group discussions and written comments were: 1) fairness, including distribution and access; 2) affordability and reliability of services; 3) physical and mental health; and 4) environmental protection.

Fairness:

The first theme identified relates to issues of fairness in the delivery of benefits across the region’s population. Participants expressed concerns over the distribution of resources and opportunities, access to services and resources, and how employment opportunities might compare to current jobs, in terms of inclusion, duration and quality. They were concerned with ensuring that segments of the population were not excluded from potential benefits, such as walking and cycling facilities, due to mental or physical abilities or location. Quality job creation was perceived as important – home retrofit interventions were seen as representing opportunities for job creation; however, concerns were raised about the potentially limited duration of interventions and the need to ensure fair pay.

Affordability:

The second theme identified was the affordability of the delivery of these measures by local and regional authorities, as well as the reliability of service delivery. Affordability was highlighted by participants in relation to all of the options, and value for money criteria, in terms of how councils would pay for these measures. The analysis highlighted that affordability (value for money) of local authorities’ initiatives and services is central to policies’ popularity. Participants also highlighted the importance of containing the cost of services, and that people should be able to afford to use them, especially given the current cost of living crisis. For example, household energy efficiency initiatives were seen as very important.

Physical and mental health:

The third theme related to the impact of measures on physical and mental health, contributing to communities’ wellbeing. Health impacts intersect with all of the options and were perceived as important not only for direct health benefits, but also in relation to quality jobs, safe and supportive communities, and providing a safe and clean local environment. Participants emphasised the importance of investing in health-related options, as they could lessen the strain on the National Health Service (NHS). For example, active travel (walking and cycling) was perceived to enhance people’s mental and physical health, by being active and losing weight. Affordable public transport was seen to provide health benefits by reducing pollution, improving people’s mental health via lower fare costs, and boosting mood via opportunities to socialise. Car-free zones were perceived as contributing positively to people’s health due to increased walking and cleaner air (improved air quality).

The health benefits of household energy efficiency were identified as being due to increased warmth and comfort, mould reduction and lower stress relating to the energy crisis. Nature-based solutions were seen as contributing to clean air (improved air quality), and to mental and physical health, for example, by providing opportunities to exercise and enjoy nature.

Environmental protection, leisure and feeling happy:

The fourth theme identified environmental protection, leisure, and feeling happy as a benefit that was relevant to many of the options and criteria. Nature-based solutions, access to a safe and clean local environment and tackling climate change were perceived by most participants as critically contributing to communities’ wellbeing. Benefits to future generations were recognised as crucial in relation to tackling climate change. Among the co-benefits of nature-based solutions identified were: enhanced biodiversity, increased wildlife, wetland restoration, CO2 emission reduction, and improved air quality. Tackling climate change was identified as the most important criterion by participants in Greater Brighton, and in the top three (along with safe and clean local environment, and quality job creation) by participants in North of Tyne. Some participants emphasised the need for serious and urgent action to tackle climate change, and many identified the need to act to benefit current and future generations.

Some participants also identified options including active travel, affordable public transport and nature-based solutions as contributing to a sense of community, through creating opportunities for socialising and community building. However, others emphasised the need for more education around the options and their potential benefits, and the importance of maintaining residents’ freedom of choice. Overall, our findings supported other work highlighting the range of social, economic and environmental co-benefits from energy demand reduction measures, in addition to their contribution to urgent action towards net-zero (Jennings et al, 2019; Jennings et al, 2020; Finn and Brockway, 2023).

Multicriteria Mapping (MCM) in focus groups

In the focus groups, a version of an approach called multicriteria mapping (MCM) was used. This explored different citizen perspectives on the options listed above, and citizens’ reasons for supporting some options more than others. Participants were first asked to score each option (from 1-100) against each wellbeing criteria i.e., to reflect how helpful they felt that measure would be in delivering that wellbeing benefit; participants were then asked to weight the importance of each criterion from 1-100, according to their personal values. These were then combined to give a weighted average score for each option. The distribution of these scores is shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11 for the two focus groups.

Figure 10 presents the weighted average of the scores that each workshop participant gave to each criterion in Brighton. Among the options, affordable public transport, nature-based solutions, and active travel received the highest scores. The average score for all 6 options was favourable (higher than 50 out of 100), but there was considerable variation between participants.

Figure 10 image description

Mitigation options Home energy efficiency, Affordable public transport, Active travel, Car-free zones, Plant-based diet, and Nature-based solutions were mapped against Health benefits, Safe and supportive communities, Value for money, Quality jobs creation, Safe and clean environment, and Tackling climate change. The results for Greater Brighton show Affordable public transport and Nature-based solutions received the highest overall scores, with all options scoring over 50 out of 100.

Figure 11 shows the weighted average of the scores for North of Tyne. Affordable public transport, home energy efficiency and nature-based solutions were respectively ranked highest. Most options had a slightly higher average positive score, compared to the Brighton group, except for plant-based diets, which had a low average approval rating of 47.9 out of 100.

Figure 11 image description

Mitigation options Home energy efficiency, Affordable public transport, Active travel, Car-free zones, Plant-based diet, and Nature-based solutions were mapped against Health benefits, Safe and supportive communities, Value for money, Quality jobs creation, Safe and clean environment, and Tackling climate change. The results for North of the Tyne show Home energy efficiency, Affordable public transport and Active travel received the highest overall scores. Plant-based diets scored the lowest, at 47.9 out of 100.

6. Delivering Local Green New Deals

Building on the citizen engagement results, in the following sections we outline policy proposals for Local Green New Deals. In this report, we focus on demand-side mitigation measures, where local and combined authorities typically have more power and influence to act, although these could be delivered in combination with local renewable energy schemes.

In Table 3 below, we outline strategic national goals that could be achieved through adopting Local Green New Deals across UK regions, together with proposed targets and costings for their implementation in the North of Tyne and Greater Brighton. These are based on regional disaggregation using local data on housing, transport, and income levels. Details of our quantitative, downscaling methodology can be found in the online Technical AnnexOpens in a new tab.

| Objectives | National goals | North of Tyne | Greater Brighton |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes | Almost all homes are EPC ‘C’ or above by 2035. Deployment of energy efficiency and heat pumps delivers a 53% reduction in CO2 emissions from homes. |

313,000 homes are retrofitted, with £1.04bn public investment in fuel poverty reduction, leveraging a total of £2.86bn. This leads to £4.72bn in bill savings by 2045, lifts 45,000 households from fuel poverty and creates around 5,000 new retrofit jobs. |

316,000 homes are retrofitted, with £286m public investment in fuel poverty reduction, leveraging a total of £2.94bn. This leads to £4.84bn in bill savings by 2045, lifts 46,000 households from fuel poverty and creates around 5,000 new retrofit jobs. |

| Affordable, sustainable public transport | By 2040, 100s of new bus routes are developed and the frequency of existing services increases, with bus journeys increasing by 66%. A 44% rise in tram, train, and metro journeys. |

Buses’ relative composition of all journeys increases from 9% to 12%. Buses are rapidly electrified, requiring £2.79bn investment by 2040. A significant £700m expansion of the Tyne and Wear Metro system. |

Buses’ relative composition of all journeys increases from 6% to 7%. Buses are rapidly electrified, requiring £2.1bn investment by 2040. The reintroduction of a tram system in Brighton and Hove, costing between £200-400m (based on systems in similar UK cities). |

| Car-free city centres and active travel | City centres are pedestrianised, cycle lanes are greatly expanded, and high streets are favoured over out-of-town shopping. Combined with improved public transport, this leads to a 21% reduction in car journeys and a 225% increase in walking and cycling. |

Car and van journeys decrease from 63% of all journeys in 2022 to only 38% in 2040. In our 2040 scenario, walking increases dramatically from 8% of all distance travelled to 27% by 2040. Cycling also increases from just 2% of distance travelled to 6%, requiring substantial investment in bicycles and cycling infrastructure – an estimated £770m. |

Car and van journeys fall from 55% of all distance travelled to just 33% by 2040. In our 2040 scenario, walking increases dramatically from 6% to 20% of all distance travelled. Cycling also increases from just 2% of distance travelled to 6%, requiring substantial investment in bicycles and cycling infrastructure – an estimated £610m. |

| Expanding green spaces and nature restoration | Nature-based solutions are promoted in preference to bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. 218.8Mt of carbon is sequestered using broadleaved native woodland, requiring 2338km2, or around 0.96% of the UK’s land area. |

Delivering the local share of afforested land hectares (Ha), would require 51 Ha in Newcastle upon Tyne, 35 Ha in North Tyneside and 4,600 Ha in Northumberland, a total of around 4,700 Ha. Using carbon credit payments, this would cost around £66m by 2040. |

Delivering the local share of afforested land hectares (Ha), would require 32 Ha in Adur, 178 Ha in Arun, 44 Ha in Brighton and Hove, 10 Ha in Crawley, 289 Ha in Lewes, 245 Ha in Mid Sussex, 9 Ha in Worthing – a total of around 800 Ha in Greater Brighton. Using carbon credit payments, this would cost around £11m by 2040. |

What policies are needed?

Some of these activities can be delivered on today, however, in many areas, local government requires greater support to deliver Local Green New Deals. The ability to implement actions is built on a combination of factors. In this report, we focus on three main areas: (1) institutions for delivery, (2) powers, and (3) funding. These are key domains of consideration but are not exhaustive. Local government action will depend on legislated powers, political will, public engagement and support, policy support, removal of barriers, finance, capacity, determination, attitude to risk and, frequently, sheer persistence.

- Institutions for delivery: The efficacy of delivering on net-zero ambitions will be determined by setting the right incentives and putting appropriate organisational structures in place to deliver on ambitions. This could include forums for discussion or delivery organisations, such as Net Zero Hubs and Joint Waste Authorities. This may require wider re-organisation of local government, though this is not something we explore in depth.

- Powers: What local authorities can and cannot do is determined by the legal framework of duties, powers and policies. Powers can be provided through primary legislation or in statutory guidance.

- Funding: From 2013, local authority funding and government-supported schemes for climate change were significantly cut. For example, a decade ago, 2.3 million energy efficiency measures were installed annually through government-backed schemes. In 2021, fewer than 100,000 were installed (CCC, 2022). It is vital that local government is given the financial ability to deliver net-zero initiatives.

6a Cheaper, warmer, zero carbon homes

Reducing energy demand from existing buildings is one of the most difficult challenges we face. Greenhouse gas emissions from housing, commercial buildings and the public sector account for around 41% of the UK’s total emissions, with housing alone contributing 30% (BEIS, 2020). Between 2005 and 2020, these emissions fell by 48%, due to energy efficiency measures and decarbonisation of the electricity supply. The key remaining source of emissions is natural gas used for heating. It is therefore vital that existing buildings are retrofitted to minimise their energy requirements and decarbonise their heating systems.

Improving our homes brings a range of benefits, including reducing energy bills and reliance on imported gas, improving public health, and generating jobs and community wealth (UKGBC, n.d.). However, recent retrofit programmes have failed to deliver at the (much-needed) scale, with roughly 16 million homes needing some form of improvement towards a reasonable standard of Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C by 2035 (The Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes report also proposes reforming the EPC system to make it more accurate and incentivise heat decarbonisation, as a key precursor to tightening these regulations). As a result, the UK’s housing stock remains poorly insulated (Nicol et al, 2016), with millions living in fuel poverty (NEA, 2022). These programmes have failed in part due to the piecemeal nature of the offer to households. A fragmented and inconsistent funding environment has plagued the UK industry in recent years, with short-lived funding horizons and complexities surrounding eligibility and implementation leading to frustration within the construction industry and apathy from the wider public.

Current strategy remains lacking, with the government’s 2021 Heat and Buildings Strategy being clear on the goals but light on funded proposals to deliver on its ambition. The basis of this strategy was the aspiration for all owner-occupied domestic properties to be brought up to EPC band C by 2035 (‘Where practical, cost-effective and affordable’.), and by 2030 for rented homes. This would give local authorities a remit to intervene to improve the energy efficiency of some 3 million homes, via minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES). Doing so would require a significant expansion of local government capacity, given that only 17 of the 268 councils have taken any action on enforcing current MEES standards, and only 17 fines have been issued (Cuff, M. 2020). Recently, the UK government

has abandoned MEES for rental properties and has disbanded the Energy Efficiency Taskforce (Cohen, 2023), meaning policy is, once again, rudderless. Similarly, it has weakened its plan to phase out the installation of gas boilers by 2035, instead aiming for an 80% reduction (Wells, 2023).

To tackle the retrofit challenge, a long-term, locally-led, centrally-funded plan is needed. This should support regional authorities to provide grants for low-income households, put in place one-stop shops, develop skills and supply chains, and support local government more widely to enforce standards.

Adopting the costings and methodology from the Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes report, we downscaled these scenarios to estimate programmes for Greater Brighton and North of Tyne, using the EPC database and local indices of multiple deprivation.

Table 4 below shows the modelled scale and impact of these programmes by 2035, with both regions seeing around 300,000 homes improved, requiring close to £3bn in investment, but generating almost £5bn in bill savings by 2045 (These bill savings also include removing VAT from energy and shifting environmental levies into taxation). Below, we set out some of the key local policy programmes which could deliver on this scale of ambition.

| – | Greater Brighton | North of Tyne |

|---|---|---|

| Share of UK programme | 1.33% | 1.29% |

| Number of affected households | 315,982 | 312,621 |

| Total Capital Investment | £2,936,500,000 | £2,862,700,000 |

| Cumulative bill saving to 2045 | £4,844,500,000 | £4,722,500,000 |

| Total CO2 saving (tonnes) | 2,885,951 | 2,813,299 |

Prioritising fuel-poor homes

In England, fuel-poor households are defined as those in low-income, low energy efficiency homes (In Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, if a household spends more than 10% of its income on fuel costs, such that the remaining household income is insufficient to maintain an adequate standard of living, the household is classified as fuel-poor). Variations in definitions and statistical delays mean that the estimated number of households in fuel poverty across the UK ranges from 4.1 million to 7.5 million (End Fuel Poverty Coalition, 2023). Many households will require grants to cover the costs of retrofitting their homes, or a blended finance approach, where the renovation costs are funded partially by grants and partially from low-interest debt. By starting with fuel-poor and low-income households, government investment will be able to address the dual climate and cost of living crises most effectively.

Grant funding can partly be drawn down from existing government funding programmes, such as the Local Authority Delivery (LAD), Home Upgrade Grant (HUG) and Energy Companies Obligation (ECO) schemes. Indeed, local authorities have already proven successful in targeting these programmes. However, committed funds of around ~£1bn/year are inadequate to meet the extent of the need. The Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes analysis estimates that at least £48.5bn of building fabric grants are needed for low-income households up until 2035. In addition, funding will be required to support households to transition from gas boilers to heat pumps. The same analysis estimates that a £9bn scrappage scheme would enable this transition, with £4.5bn ringfenced for low-income households.

Figure 12 image description

The lowest income decile homes (1) receive 100% grant funding, decile homes 2 receive 80%, 3 receive 60%, 4 receive 40%, and 5 and above receive 20%. There is a greater number of homes in decile 1 in North of Tyne, and fewer in deciles 4 to 9 leading to far greater public investment than in Greater Brighton – £1,045,000,000 in North of Tyne, and £286,300,00 in Greater Brighton.

However, this share of investment is not equal in both locations. The indicative proposed blended finance programme (Figure 12) assumes that homes in the lowest income decile 1 receive 100% grant funding, with deciles 2, 3, 4 and 5 receiving 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% grant shares, respectively. When examining the relative share of households in different income deciles, a far greater share of households in North of Tyne are in the lowest income deciles than in Greater Brighton, and thus receive a much greater share of public investment, with £1,045,000,000 and £286,300,000, respectively.

Public funding for retrofit has typically been short-term and competitive, with funding often only available over short, one-to-three-year funding cycles. This has not given businesses the confidence they need to invest in training and equipment. To address this, any local programme should be accompanied by long-term commitments. While grants will be required for those on low incomes, low-interest debt and blended finance can be suitable for more able-to-pay groups. To enable this, government, via the Treasury and Bank of England, can provide debt at subsidised interest rates to local government. This would enable local actors to set up local low-interest loan schemes. These blended financing offers could then be overseen by the local Retrofit Taskforce and one-stop shop.

Local Retrofit Taskforce and one-stop shops

Retrofitting is often a complicated process, involving many stakeholders (Figure 13). A council-operated ‘one-stop shop’ approach could overcome some of these barriers, by operating as a central point of information and delivery support for residents.

Correctly designed, one-stop shops can effectively raise awareness of the need for retrofit, signpost residents to key resources, and collate information on home assessments, financing options, and contractors for residents. INNOVATE, as well as the UK Green Building Council Retrofit Playbook (UKGBC, 2021) and Local Partnership’s Local Authority Domestic Retrofit Handbook (Local Partnerships, 2023), have compiled helpful resources on setting up a one-stop shop. Retrofitworks – a not-for-profit cooperative of contractors, tradespeople, and community groups – is also active in establishing and promoting one-stop shops across the UK.

Figure 13 image description

- The retrofit customer journey begins at the Entry / trigger point, generated by marketing and outreach, featuring trading standards policy.

- Step 2 is advice and audit through an energy advice service and policy such as EPC or SAP ratings.

- Step 3 is specification and budget through a retrofit designer or architect, and uses policies such as building regulations, RIBA or ARB.

- Step 4 is contractor procurement where the installer is engaged using policies such as public procurement guidelines and competent persons schemes.

- Step 5 is funding and finance through a bank or lender, utilising policies such as ECO, LAD, and FCA regulations.

- Step 6 is installation & quality assurance checked by a retrofit coordinator or building control, and managed through policies such as PAS 2030 / 2035, and HSE.

Coordinating action on retrofit requires a staff team focused on the mission of achieving the retrofit task. One of the most binding constraints on councils is their limited staffing. To overcome this, councils and combined authorities could be supported to put together a Retrofit Taskforce, made up of local and regional government representatives, social landlords, the construction industry, colleges, energy suppliers, industry experts, and investors. Significantly, the taskforce should work in partnership with a regional group of councils, with each dedicating resources and staff to underpin the function of the taskforce. Such an approach has recently begun in both Greater Brighton and Greater Manchester.

The taskforce can develop a delivery plan that is most suitable for the local housing stock, push forward a series of agreed actions, and maximise investment and public funding, particularly to support those least able to pay for retrofitting measures. Managing the retrofit scheme through a designated taskforce can ensure resources are used effectively, and that oversight is maintained across the whole project. The Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes programme estimated that these local delivery units, alongside citizen engagement and a public information programme, would require around £2bn for a 10-year programme. When downscaling to the regional level, we expect these programmes to require around £27 million in Greater Brighton and £26 million in North of Tyne, or around £2.6 million per year, per region.

Engaging citizens

Reaching net-zero requires citizens to be fully engaged and empowered. Many of the urgent changes and decisions to drastically reduce emissions have a strong local dimension. Government can support local leaders to implement neighbourhood or community-based outreach and mobilisation, which can be critical in overcoming barriers to retrofit. By informing, consulting, involving, co-designing, and empowering, local authorities can convey information on the benefits or processes of retrofit to potential customers more effectively than traditional marketing approaches, and make use of trusted information channels, such as neighbourhood associations and faith groups. Engagement with community groups and local stakeholders can drive greater take-up amongst a wider network of people, by leveraging high levels of trust to overcome barriers to retrofit more effectively.

Therefore, council-led one-stop shops should focus on building community capacity and a personal approach. This should be tailored to reach target communities such as older residents, black and minority ethnic communities, and people who speak English as an additional language. Outreach efforts should also highlight the cost savings of a neighbourhood-based approach. For example, by working on properties simultaneously, Bristol Green Doors facilitated significant savings (approximately £500 in installation costs per household) by retrofitting ten or more properties. Householders involved agreed they would not have taken part in the scheme without grant funding to offset expenses or the support provided by Bristol Green Doors. By identifying and supporting community champions and early adopters of retrofit, local government-led one-stop shops can strengthen local networks and secure long-term commitment to the initiative.

One-stop shop example: Social Economy Retrofit (SELCE)

The South East London Community Energy Co-op (SELCE) provides free energy advice and support, and is partly funded by local government to support community engagement. It was founded by local volunteers concerned about the climate crisis and is a Society for Community Benefit. It works in partnership across Greenwich, Lewisham, Bromley and Bexley with local organisations and councils, to help individuals, businesses and community organisations to navigate the transition to sustainable energy. They offer a range of impartial advice services to help people who are struggling with their energy bills, households who want to retrofit their property, and organisations that are looking to become more sustainable.

Building a skilled workforce

To deliver at the scale required, it is essential that the skills and the workforce for low-energy construction activities are in sufficient supply. To achieve this, the number of appropriately trained net-zero construction workers will need to rise rapidly.

The Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes report estimates that the programme would create ~260,000 new construction jobs, with an additional ~230,000 indirect jobs in related supply chains. Our downscaling analysis estimates this would require 5,285 newly trained apprentices in Greater Brighton and 5,229 in North of Tyne.

Local leaders will need to map the demand for retrofit against the current supply of retrofit capacity, and use this as the basis for a local strategy that addresses existing skills gaps. Councils and combined authorities should engage local businesses, colleges, and community groups throughout this process. They should also build a retraining plan that targets certain cohorts of the existing workforce, for instance, those with specific skills levels.

While long-term funding for retrofit will itself catalyse businesses to invest in skills, some additional support will be needed for local government to enable this. The Cheaper Bills, Warmer Homes analysis estimates that an additional £400m for new apprenticeships and £100m retraining fund for existing trades would be required for local leaders to deliver ~200,000 new apprenticeships and retraining programmes via local Further Education (FE) colleges. We estimate this requires around £6,448,000 for new apprenticeships in North of Tyne and £6,627,000 in Greater Brighton during the 2020s.

Local one-stop shops should use their procurement systems to support the development of inclusive economies, via Community Wealth Building. To do this, local government should embed its strategic aims into its procurement system, such as by ensuring that council construction contracts meet certain diversity-related targets and higher energy efficiency standards. Strategic insourcing can also play a role and has been used by councils across the country, from Islington to Preston, to improve living standards in their areas. Nottingham City Council, Leicester City Council, Glasgow City Council, and others have established arms-length construction organisations.

These organisations more proactively include women and ethnic minorities, can offer greater opportunities for new entrants to the sector, offer more secure forms of employment, and build to higher standards. Councils ought to identify how they can achieve similar outcomes through their procurement powers, and consider whether in-sourcing construction would more effectively achieve their goals.

Retrofit policy recommendations

Institutions for delivery:

- Central government puts in place a 10-year Local Retrofit Delivery framework. This would support combined authorities and county councils to establish local one-stop shops and Retrofit Taskforces with dedicated staff that support residents to decarbonise their homes.

- Central expertise to support implementation. In addition to devolving funding and responsibilities to local government, it is important that central government provides leadership on best practice in financing, engagement, and skills. The new National Retrofit Hub could be the vehicle for this.

- Citizen engagement. Central government needs to lead the way in engaging the public on the retrofit challenge. Through clear, effective communication, government should make it clear that retrofit is a well-funded national priority. However, local community groups should be provided with the resources to engage citizens on the benefits of these approaches.

- Councils should establish new training courses for tradespeople and skills accreditation, and signpost residents to local, trusted tradespeople. This should be funded by central government.

- Local government should support community organisations and establish direct labour organisations and cooperative development agencies, so that the public money invested in retrofit most inclusively translates into economic opportunities for communities.

Powers:

- Retrofit and fuel poverty delivery should be devolved to local and combined authorities with long-term funding horizons (5+ years) and greater autonomy in how these schemes are designed.

- Government should reintroduce and strengthen Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) and devolve enforcement to local government. Government should build local capacity so that councils are able to undertake this task.

- Amend legislation to allow for the introduction of Property-Linked Finance so that the UK can learn from the experience of US counterparts and fully leverage private investment. This type of lending is viewed as lower risk by lenders but will require higher consumer protections to ensure successful implementation (Green Finance Institute, 2022).

Funding:

- National government should allocate £2bn to the Local Retrofit Delivery Framework for devolved administrations, combined authorities, county councils and local authorities. These programmes should look to serve all tenures and local housing types but should prioritise areas of high fuel poverty.

- A programme of grant funding, targeted at low-income households. Central government should make £48.5bn of building fabric grants available for low-income households to retrofit their homes. £9bn should be available for a heat pump boiler scrappage programme, with £4.5bn ringfenced for low-income households. This funding should be committed to for at least 10 years.

- Blended finance. Central government should develop a blended financing offer, tied to the property, not the individual. Combining low-interest debt with grant funding via the Treasury and Bank of England should enable local one-stop shops to offer blended finance to all residents, regardless of income.

6b Affordable, sustainable public transport